American Photography at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, is a chilling yet fascinating archive of the USA’s photographic history. Tracing the development of the art, from early daguerreotypes to celebrity portraiture, it features staple works from the country’s most sensitive creatives, lesser-known gems from contemporary photographers, and a broad catalogue of amateur works that capture American culture at various stages of its development. However, its truly unique aspect as an exhibition draws from its place as a foreign eye on the predominant cultural superpower of the 20th Century.

During my visit to the Rijksmuseum, I was fortunate enough to join a group of journalists and art professionals on a tour of its most iconic works from Dutch history. Alongside a thrilling chance to witness Rembrandt’s The Night Watch being restored, while being able to speak directly with the conservator behind its protective glass wall, the group was led toward the Dolls’ house of Petronella Oortman. A 17th Century piece of luxury decor, once belonging to the wife of a particularly successful Dutch merchant, the house is an elaborate miniature of an Amsterdam mansion, complete with minute details of all kinds. Observing the tables and chairs, tiny frescos, and wooden panelling, visitors can discover a sophisticated visual history of Amsterdam’s most wealthy tradesmen and their families. It’s a fascinating object to display, not just in a museum, but for its function in a domestic environment too. An ornate celebration of a lost present, a moment in history, it acts as a curious statement proffering the ideality of everyday life at the time of its creation, over and above the importance of religion or other abstract philosophies that inform interior design choices. Preserved across time, it now offers museum visitors the chance to peer into another world from the outside. Likewise, American Photography provides a similar miniature of a foreign culture, displaced in time and space.

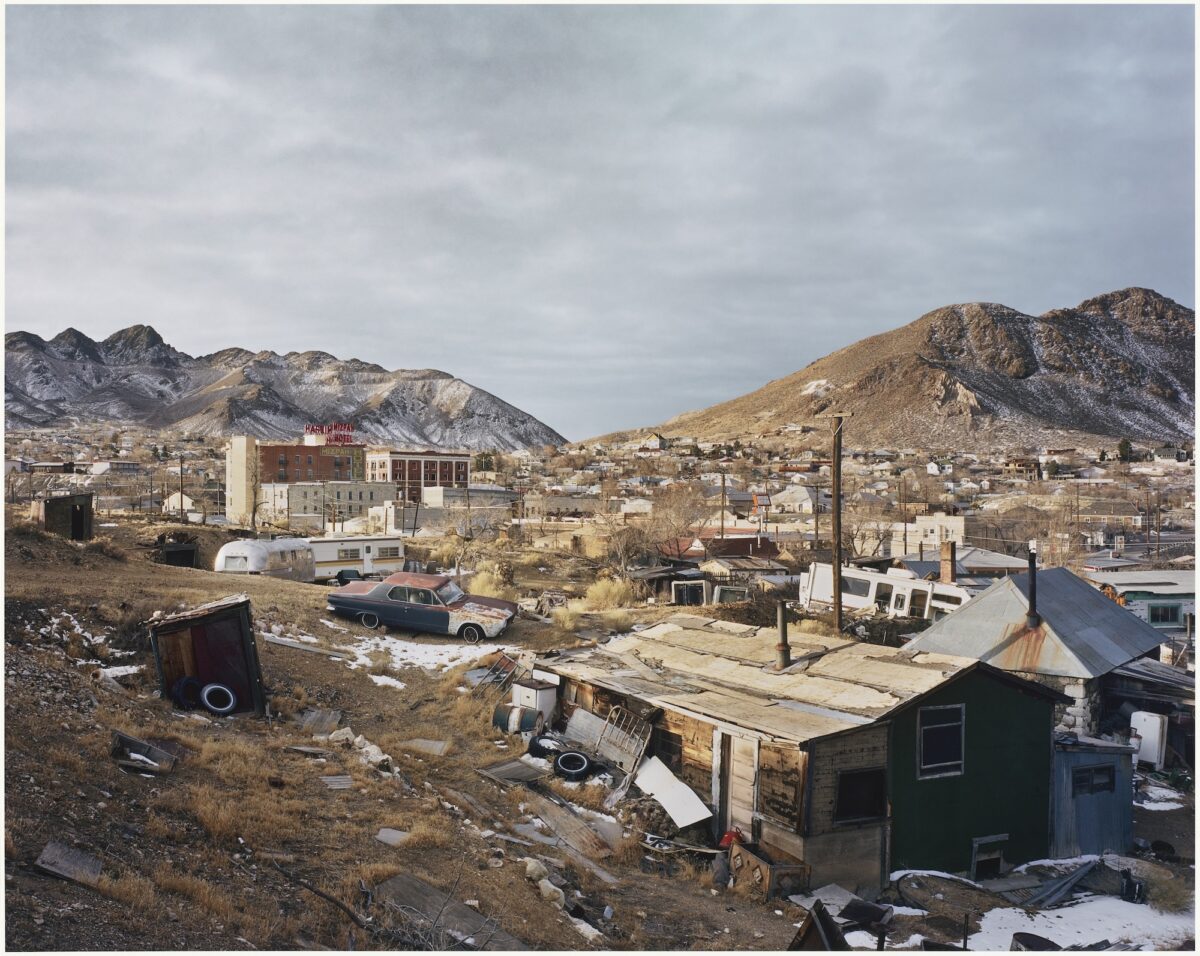

A step through the gallery doors reveals the first of many rooms that archive, dissect, and tinker with the values and experiences of American culture. The themes are immediately apparent. Domestic strife, racial politics, the suppression of queer identities, sexuality, ecology, and individuality; each of these ideas finds its example, its case. Whether considering the dual personalities in Robert Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits, the interweaving of indigenous art practices with modern photography in Sarah Sense’s work Hinushi 18, or the few surviving artefacts of the country’s abandoned towns in Bryan Schutmaat’s landscapes, the overall impression resounds. America is a nation at war with itself. Conflict, reflected in the photography, regarded as an essential component of the modern experience of life in the USA.

The results of these battles are morbid and cruel. One photograph, from Nina Berman’s collection Marine Wedding, depicts the marriage of a disfigured soldier sent to fight in one of the American governments many international warzones. Described simply by the accompanying placard, the viewer is informed that the marriage broke up, and that soldier had died from alcohol and morphine overdose since. Likewise, the piercing work of Nan Goldin chronicles her experiences with domestic violence and the AIDS crisis as it ravaged New York. In Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City 1986, Cookie Mueller, featured in another depiction of a wedding, walks the aisle with her soon-to-be husband, though anyone who knows the story will understand how tragic this became after the fact, as they both died shortly afterward.

The show itself is fascinating, primarily because of the artists and their work. It can be brutal, but it’s nevertheless enlightening. However, owing partly to the scopophilic nature of photography as an art, because of its nature as a medium that can only record what’s placed before it, that to some degree always overleaps the boundaries of sole representation to depicting the real lives and people that form its subjects, the show becomes a very sombre experience. It’s difficult to disconnect from the sense of voyeurism that forms the atmosphere of an exhibition with such a broad scope, the intimation of loss hanging in the air above the photographs. Perhaps, owing to its detachment from the culture that produced the images it showcases, American Photography can see it more clearly. The history of that culture has been historically largely defined by this foreign perspective, either through bringing in new voices from across its borders or through American artists themselves travelling abroad and gaining a new insight into their nation from far away. Distance is key, but it simultaneously isolates the viewer from the work, and the works from one another, bolstering the show’s mournful overtones.

But it’s a must see for anyone visiting Amsterdam.

Channelling the grief, the overriding emotion of the gallery space, and focusing it on the attempt to connect with the subjects of its photography despite this distance, provides an opportunity to charge the works on display with a heightened meaning. In particular, I found myself focused intently on Mapplethorpe’s portraits, the power of the images, the presence of an individual hardly given room to breathe amid the dominant climate of his culture, yet present, nonetheless. American Photography should be approached slowly, carefully, with exactly this degree of attention given to each of its artists and subjects at large. Look into the eyes, where you can, and try to get a sense of the people on the other side of the camera, watching you.

American Photography, 7th February to 9th June 2025, Rijksmuseum