American-Iranian London-based painter Kofi Perry recently sat down with art historian, writer and curator Hector Campbell to discuss his interest in Afrofuturist and European art history, ‘coolness’ as a Black cultural phenomenon, his preference for traditional mediums and materials, and his upcoming solo booth at 1-54 art fair with DADA Gallery.

Hector Campbell: Having grown-up in America, you began your artistic education at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, before transferring to City and Guilds of London Art School. How did that move to London influence your practice? And are there any key differences that you discerned between US and UK art school experiences?

Kofi Perry: Going to PAFA was a unique experience because their program is focused on traditional painting, drawing and sculpture, and the teachers there are good at inducting you into that world. So I became really invested in learning those skills. We had set classes on various subjects and in that sense it was like a typical American college experience. When I transferred to City & Guilds, I immediately felt like I was left to my own devices because there weren’t really any set classes. I was more or less just in my studio and having tutorials with tutors one-on-one. So in my head, I thought I was given the skills to make art at PAFA, and City and Guilds could be my introduction to contemporary art, which was an aspect PAFA’s program kind of lacked. I spent a lot more time at City and Guilds collecting references and developing artist statements.

H.C: Rather than painting from life or photographs, your practice is rooted in repetitive preparatory drawings. How important is this repetition in defining your finished paintings? And what drew you to that preference over the use of from life observation?

K.P: I first heard of the idea that you could paint and draw figures from your imagination from one of my teachers, and ever since that moment I kind of became obsessed with it. As I slowly develop that muscle, I also learned why it’s so enticing. I think there’s a very distinct power and thrill to having a complete figure or world already in your head that you can conjure at will. And of course the method often requires having to repeat drawings to make them better. I also repeat colour studies and small scale studies of paintings before I commit to the finals. I think of them all as rehearsals. Also, perhaps deep down, this repetition in my practice reminds me of my ten-year-long passion for martial arts in my teenage years, and the form routines I loved to repeat.

H.C: The use of world-building looms large over your output, with paintings and drawings featuring characters and scenes from your own imagined Afrofuturist reality. How well-rounded is that world in your own mind? And how did you arrive at this afrofuturist fictionalisation?

K.P: I arrived at Afrofuturist worldbuilding through quite a long journey. When I was five or six, in Lebanon, I used to write and bind my own high fantasy books complete with illustrations. I think I was doing that to copy my dad, who’s an author, and as a response to all the archaeological stuff in Lebanon and the fantasy movies and books I’d seen. That interest never really went away. Once I was studying at art school and thinking of how I could make use of my art skills, I decided to paint characters and stories that could satisfy my interest in high fantasy, while also finally inserting my own representation in the genre.

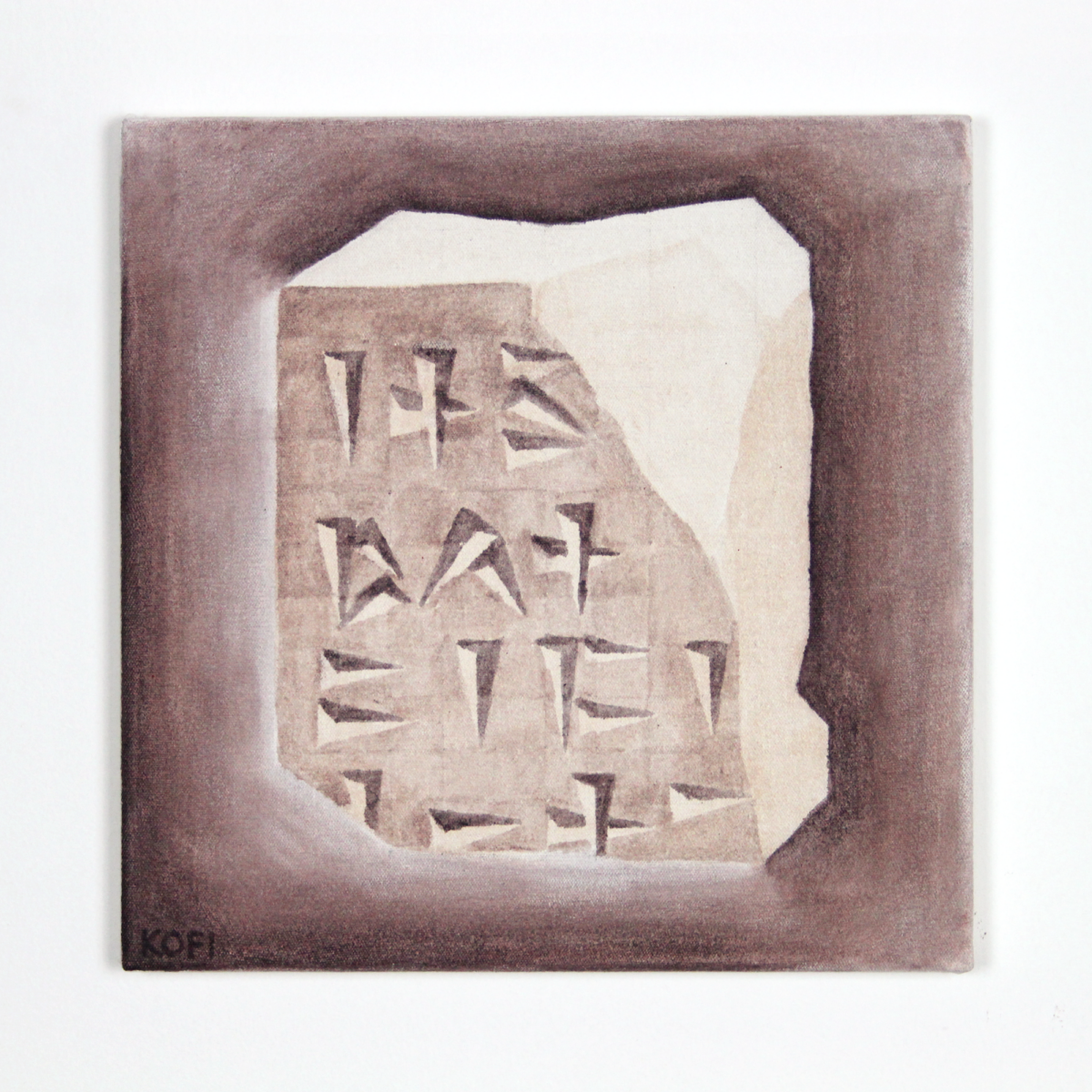

What also influenced me were the figurative works of other Black PAFA alumni Barkley L. Hendrix and Henry Ossawa Tanner. At first I called what I was doing “Afrocentric Fantasy”, but later I realised the umbrella term Afrofuturism was more useful. While working on this fictional world, I decided for myself not to share the details explicitly through texts, but rather to let them out bit by bit through my paintings. But much of it is already fleshed out – origin myths, religions, settings, and notable events.

H.C: You’ve spoken about the “visual quality of coolness”, as well as your interest in understanding or subverting the gaze, and your paintings show a clear command of pose, poise, light, shade and shadow. Could you expand upon these underlying concepts, and their influence on composition?

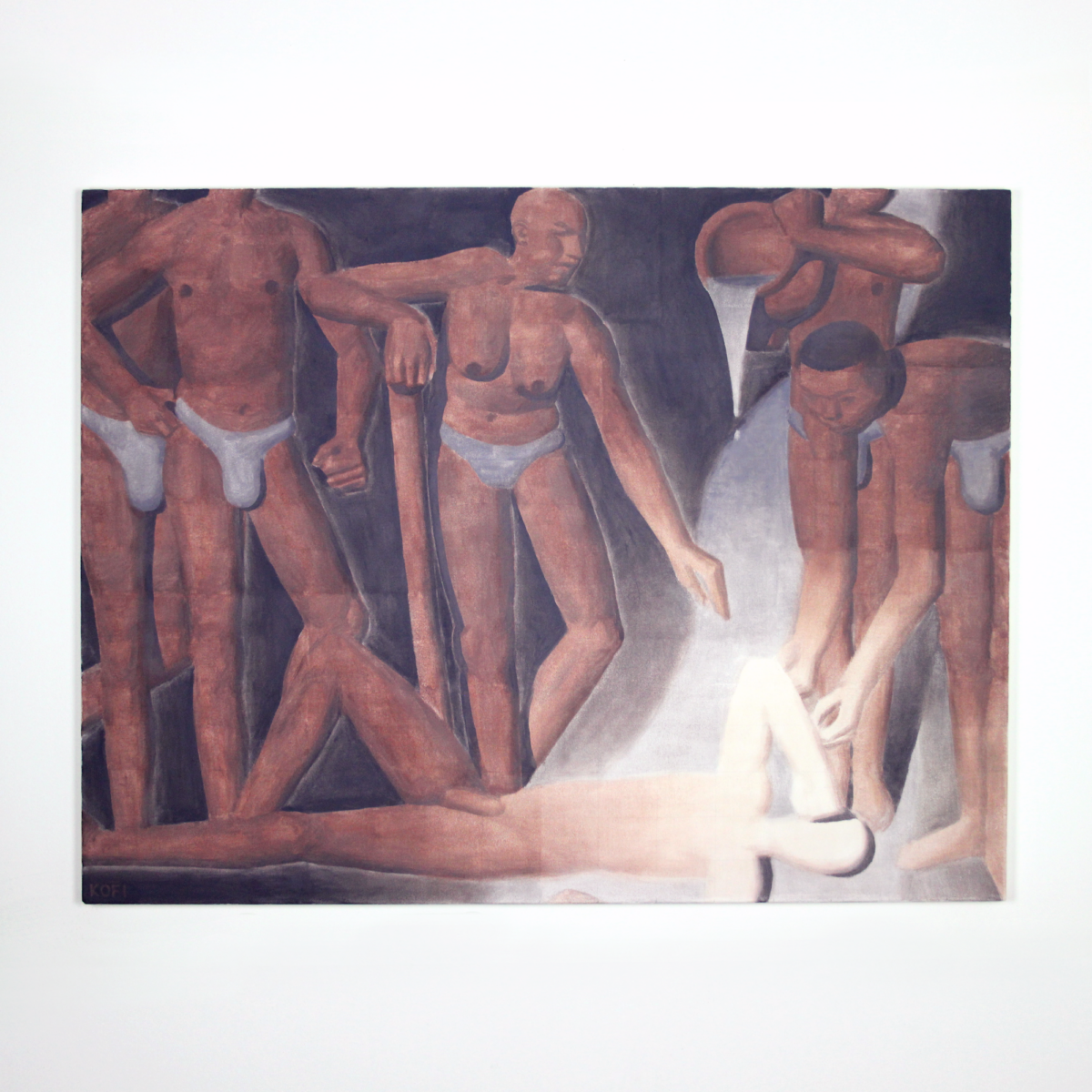

K.P: My interest in coolness began in 2020 when I shifted from making master copies towards making my own work. I was trying to find a distinctly Black American visual language to use in my art, and what I landed on was the concept of coolness. I think it’s a cultural phenomena found not only in Black fine art, but also in our music, dance, and film; I feel like it’s just embedded in the culture itself. I know that some scholars have traced it back to pre-colonial West Africa, and social scientists have written about it under the term “cool pose”. To me, in an American context, it ultimately represents a defiance of White supremacy. The most readily available way for me to express coolness in figuration is through a character’s gaze and stance.

Aside from that, my compositions and techniques are really inspired by 19th century European artists like Ingres and Degas, who themselves took from the ancient Greeks. I trace the Greek figurative model back to the ancient Egyptians. Lately, I’ve been trying to find a common thread between all these sources through what I’ve come to call “universal classism”, or the shared visual traits I’ve found among art from ancient civilizations globally. They’re tropes like broad forms, frieze compositions, and anatomical idealizations.

H.C: Materially you employ a range of more traditional or antiquated techniques, including the use of essence, conté and stumped charcoal. What drew you to the use of these more out-moded mediums? And what do you aim to achieve by combining them with a contemporary artistic vision?

K.P: Essence for painting and hard graphite for drawing are the two mediums I’ve settled on for now. I discovered them while researching the methods of Degas and Ingres. I’ve never liked impasto in oil painting or glossy paint in general, and essence is extremely matte and flat while being more forgiving and chromatic than watercolour or gouache. Hard graphite on paper became my preferred medium back when I made copies of old master drawings, and it’s now my go-to when drawing. These days, I want to reach even further back in history and explore fresco painting. The fact that not many contemporary artists work with or even know these mediums, and their juxtaposition against the futuristic elements of my art, both make them exciting to me.

H.C: Similarly, you’ve spoken often of your interest in art history and the conventional European visual language, even presenting your own curated selection of 20th-century British painting alongside your debut solo exhibition ‘Remnants From the Distant Future’ at Lightbox Gallery (Woking, 2024). Where did this art historical interest begin? And how does it continue to inform your practice?

K.P: Had it not been for my cult-ish induction into art history at PAFA, I don’t think I ever would’ve taken a liking to this type of art. My journey since then has felt like slowly leaving a nest. My relationship to old European art is ongoing, and I think that presentation of Ingram collection works at my Lightbox solo show spoke to my current feelings. Jo Baring, the director of the Ingram Collection, helped curate the show to compare and contrast these older works with my own. Some of my techniques were identical to those older artists, but the subjects and messages were antithetical.

H.C: Contemporary cultural interests such as hip-hop, science fiction and comic book superheroes have all influenced your practice in various forms. Could you speak a little to these reference points and their importance to you?

K.P: Hip-hop culture was a natural thing to include in my visual art because for three years before art school I was actually producing beats inspired by 90’s and early 2000’s artists like J Dilla and Madlib. The choice to begin a career in visual art rather than music was hard for me, so merging the two felt like a nice compromise. Hip-hop makes its way into my pictures mostly via its character archetypes, moods, and its album cover artworks.

The science fiction and superhero references in my work are actually taken almost exclusively from one source: the Pixar movie The Incredibles. I’m obsessed with that movie’s aesthetics. I haven’t watched it in years (and I don’t intend to in case it lets me down), but my memory of the art design is beautifully Art Deco, sci-fi, tropical, and James Bond-esque. And I like the idea of a superhero as a symbol for the Herculean (or even mundane) efforts that Black and Brown people make to protect ourselves and each other from racism and societal oppression. And of course, the outer space themes of original Afrofuturists like Sun ra and George Clinton have made a strong impact on my work.

H.C: Finally, you will be presenting your latest body of work at 1-54 art fair with DADA Gallery. Could you give us some insight into what to expect?

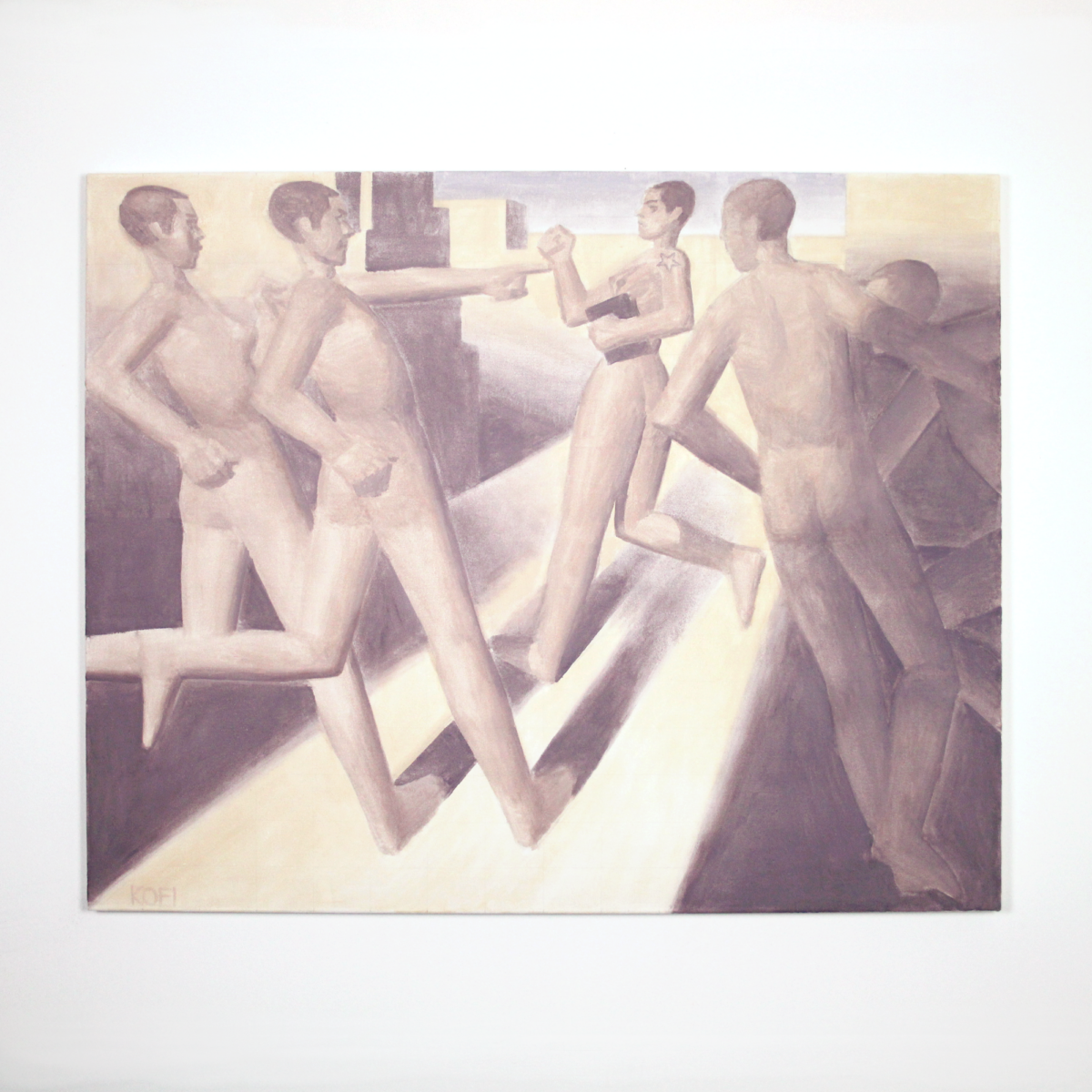

K.P: Yes, for my solo booth at 1-54 I’m presenting several large multi-figure narrative paintings, a few small still lifes, and some drawings. I’m revisiting characters and stories from previous paintings in order to expound on and canonise the lore of my world. I’m also introducing some new features in my compositions – namely a sense of glowing light, and a focus on athleticism as a symbol for the physical, emotional, and psychological fitness required of Black and Brown people to navigate life in predominantly White societies.

1-54 is the first and only international art fair dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora. Returning to Somerset House for its 12th London edition, this Friday (11am-7pm), Saturday (11am-7pm) and Sunday (11am-6pm)