Entering the chapel at Mount Stuart, I am wrapped in an immensity of white marble. Abruptly, a shock of green enters my field of vision. Planted in front of the altar, a single word, CRIOCH. “End, Border, Finished,” Byrne explains, “like at the end of a play, but in French it’s ‘finis’ which is quite elegant. In Gaelic it’s much more….” he pauses and with a wry smile slices his hand across his throat in a mock-decapitation, “Final.” Here, the painting’s placement is a tongue-in-cheek confrontation, a border made manifest, and a reference to the quashing of the Gaelic language by the English.

Just upstairs in the red-swathed bedroom of Lady Bute, Molly’s cry, “Yes Yes” –cited from Ulysses–hangs above the bed. It’s the type of witty wordplay, linguistic orchestration woven into Byrne’s work.

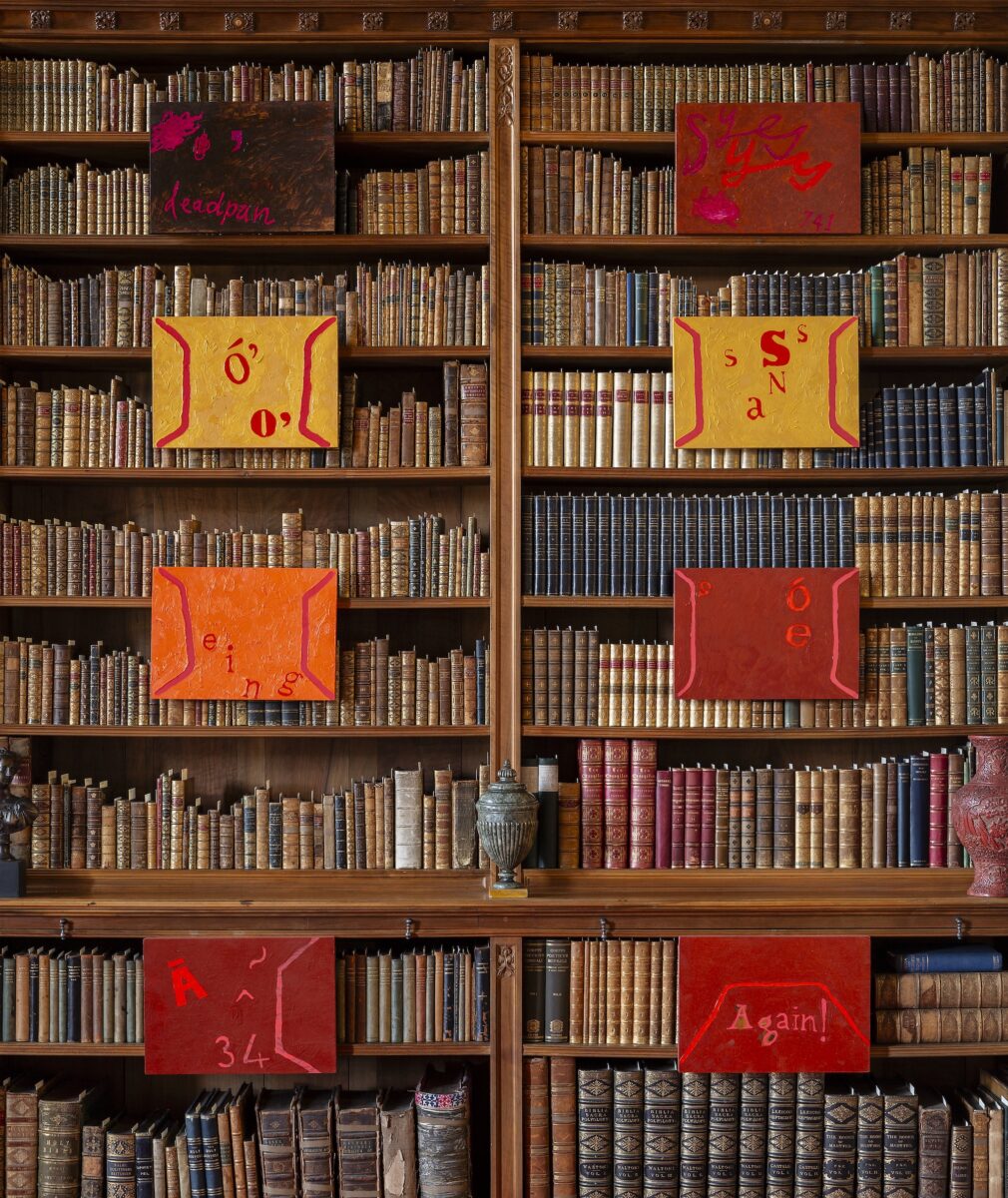

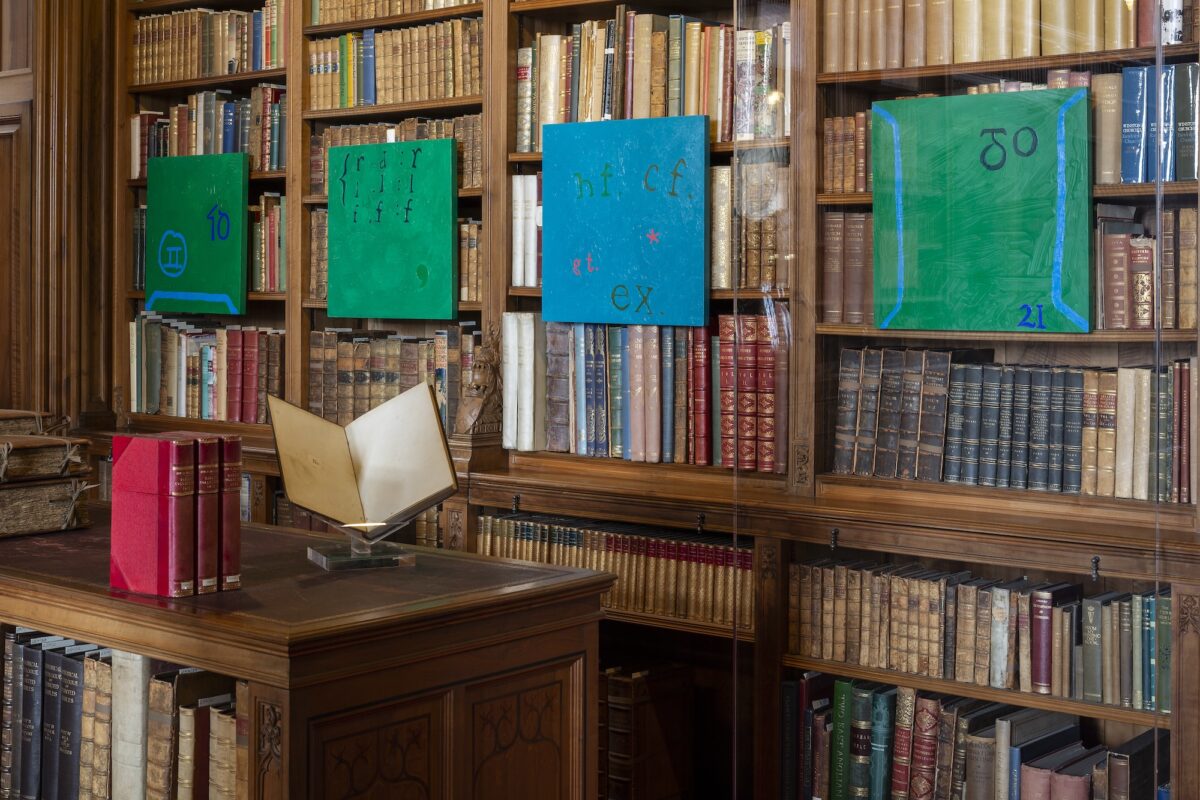

A jaunty investigation into typeface, linguistics, and literature, the paintings feature letters spliced together from Gaelic texts in the Mount Stuart archive and the artist’s own collection. Some letters hop and wink, others languish across the canvas in long tonal vowel sounds. The result is a permutation of language, in which the letters themselves seem to be conducted by Byrne’s own hand, punctuating the canvas. Looking at a Byrne painting is a visual exercise that likens itself to reading music.

The interplay of mediums is perhaps unconscious, but music itself is central to Byrne’s practice. Piecing overheard-remembered conversations together with personal writings, Byrne has a penchant for taking the juiciest bites of language and rearranging them in a manner that invites the viewer to chew it over a time or two. The low baritone of Byrne’s voice cuts through the marble-hollow white noise, “Where there is no more world, where there is no world yet. UNPERFORM.” My eyes are drawn to the screen where Byrne’s piercing gaze on 16mm stares me down. I have the feeling of being pinned in place. This imaginative, paradoxical word “UNPERFORM” calls-out the impossibility of not performing and doubles as a call to action, to perform less and perhaps to act natural (a concept which can be traced back to the artist’s 2022 show “Act Natural” at Amanda Wilkinson Gallery in London).

The exhibition’s title “smell the book” conceals another would-be instruction. Byrne explores all the laughter and levity to be found in language, for those who hold it in their hands with the highest esteem and the proper irreverence, for those who look and touch and taste and smell it and (most crucially) for those who play with language. I, for one, left feeling inspired to do just that.

Oisín Byrne’s “smell the book” is on view at Mount Stuart from 31st August to 20th October 2024.

Our conversation below.

Let’s start with the title “smell the book” much of your work crosses disciplines, senses and mediums. What were you aiming to evoke and can you give an overview of what visitors can expect?

The title of the show comes from a song that I wrote. In a moment of grief, I was sitting with a book and the air suddenly had this strange sweetness. I smelled the book, then smelled my knee. The scent was coming from neither – it was perceptual – a smell inside my sensing. In another way, it was coming from the book, which had invited a state of being. The song itself is included in the exhibition, which is a collection of paintings, songs, and films, creating a network of citation, gathered around language.

Your film “A PAIXAO” exploring an encounter with Clarice Lispector is perhaps a good example of this….

A PAIXAO is an imagined encounter with Ukrainian born Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. When I read Clarice, more than almost any writer, I seem to meet my own interiority on the page. Since I was young, I’ve had a relationship with books that wasn’t always about reading cover to cover. As a teenager I would sleep with a given book under my pillow, hoping to imbibe it in my sleep. The paintings in the exhibition – along with A PAIXAO – describe a kind of hallucinatory space I go to when I’m reading – – – it’s as much about the space between words, the moments when I stop reading and sit in the air of the book – – – the words and letters float in the air like musical notation.

Do you think more people should start smelling books? Having a multisensory relationship with literature?

I guess that sometimes when we read books we shoot for understanding, which in some cases isn’t possible in any complete sense. Even with a full set of annotated notes, one could never fully surmount the references and inflections of Finnegans Wake. Perhaps knowing before you begin that an absolute understanding is impossible, instead of being terrified, there is an invitation to approach the book in a way which is like hearing rather than reading, more like being immersed in it than the arbiter of its meanings.

The starting point for the exhibition was the collection of Gaelic and Irish pamphlets within the archival collection at Mount Stuart. Having visited the archives myself, I am aware of just how vast their holdings are (some 27,000 volumes line the shelves of the historic libraries). You’ve also included modern authors from your own collection. How did you draw these initial connections and what did the process of selecting the texts look like?

I worked with Elizabeth Ingham at the archive which was thrilling. Our approach to finding texts was a combination of decision making and instinct: more like following a scent (to tire that particular metaphor) than a set of parameters.I was immediately drawn to Donald Maclean’s large collection of Gaelic books and pamphlets at Mount Stuart. The large majority of these are either song books (including a book with the enviable title “Mouth Tunes”, which records songs passed down orally), books of grammar, or ecclesiastical books. Though I do have Gaeilge, it is by no means liofa or fluent. Some of these texts and translations really had a wide reach internationally. Ossian, a collection of epic poems published by McPherson and based on collected word of mouth material in Scottish Gaelic, was lauded by Goethe and Diderot amongst others.

This body of work is really a contemporary framing of the Gaelic language. Would you agree and can you discuss your relationship to language, as an Irish artist?

I’m interested in the ways in which Gaeilge has influenced the way the Irish speak and write English – the syntactic anomalies. For example, in Gaeilge, instead of saying “I am happy” or “I am sad”, one says “happiness is upon me” or “sadness is upon me”. The “I am” form in English implies the emotion is a fixed identity – the “upon me” form seems much more apposite – emotions as temporary weather systems. Here, the grammar of a language describes a state of mind, a way of being.

It seems to me no coincidence that so much brilliant modernist and metafictional writing came from Ireland in the 20th Century. Jamie O’Neill writes about a joyful disregard for ‘proper’ usage: “In Ireland we have a playfulness with our English. The language is not a national treasure. It’s a borrowed thing, a loaned vocabulary on an older Gaelic syntax”. He writes about taking a Chippendale and using it on the fire, for “low use”, to create heat. Speaking a language which is not one’s own – which has been imposed on you – produces a kind of ludic irreverence, or proper disrespect for the rules and regulations of the coloniser’s tongue – and more adventurous writing in English. This thread between Gaeilge and modernism was one that I wanted to gently draw out by taking letterforms not just from the archive, but from my own collection of books, that span through early Irish modernism to sci-fi feminism and beyond.

Yes, the paintings include specific letters and typography from different books. Why did you select these as subjects?

The alphabet is in effect an open source technology. The same ‘e’ sits in a tax report as a great literary text. I had this marvel in thinking about the letter ‘e’ in Clarice Lispector’s hands – how she used the same material we use every day in more or less banal ways to create something that didn’t exist before. And somehow I wanted to take just that – the typographic ‘e’ from a particular book by a particular author, like a strand of DNA – and have it writ large as a sculptural form on canvas. I wanted the works to remain buoyant, undefined; yet at the same time they are some of the densest paintings I have made to date.

Can you touch on the materiality of the canvases and their compositional forms? The reddish brown pigment gives them a leather like quality.

These paintings – titled Glossia as a set – are oil paint on linen. The rusty red is more like a material than a colour, applied thickly. It is like the leather of binding or porphyry marble. The composition of the works includes painted linear straps at either side – which I originally saw as the edges of a book. They create a very rudimentary perspectival space in which the letters move about. I later began seeing these as markings on a game field, as reverse parenthesis, and most recently as the edges of a throat. In the exhibition text Daisy Lafarge suggests that the throat, “equidistant from both the rumination of the gut and the scrutinising purview of the brain”, is an appropriate place to keep these letters.

And many works feature vowels and vowel sounds….

Yes! Vowels seemed to be turning up in these paintings much more often than consonants. Vowels are more oral, more of an open mouthed sound than consonants. I remember when you first saw the paintings, you told me about an Egyptian song containing only vowels – composed to subdue the forces of nature. Can you remind me of this?

Yes, Lipchitz made a sculpture on the subject for Madame de Maudrot’s house at Le Pradet. He had heard about a song used in ancient Egyptian prayer composed completely of vowel sounds. The Egyptian song is not well documented, but we know that the mysticism of the vowel sound is recognized across cultures, religions, and geography. Gnostic and Gregorian chant both lean heavily on vowels-“EUOUAE” in Latin psalters-as does the “OM” chant, the sound of the universe. And yes, the Egyptians believed the vowel sounds could shape nature. In the exhibition text, Daisy Lafarge references your interest in nature shaping language, another thread connecting vowels and the natural world.

Love this! Thank you. And yes, I spoke with Daisy about rough climates or vast landscapes producing accents with extended vowel sounds. The longer vowel sounds allow the voice to travel, amplifying the words to carry through wind or distance.

Fascinating! On the subject of amplifying words, your electro-pop songs are inspired and pulled from overheard and remembered conversations, personal writings, and cultural quotation. These have been described by Eva Wilson as ‘citational anthems’. Can you tell us about your songwriting process? How do you determine what makes it into a song?

I sellotape together orphan sentences from my essays with overheard phrases and quotations. Wayne Koestenbaum writes about how singing operates in a separate domain to speech — it is outside of, excluded from, liberated from Foucauldian avowal and truth-telling. The fact that something is sung already signals “I am performing myself”. One can sing a secret and it remains secret: to sing is to express not a destination but a process.

For this exhibit your songs were scored to string quartet by Naoise Hardiman May. What was the impetus for the transition into classical.

I’ve always wanted to work with a string quartet or orchestra – there is something about the simultaneous depth and spareness of string music that I hoped would work with the linguistic density of my songs. I did worry that the strings would produce an earnestness that I might be suspicious of – but it turns out the lyrics have enough irony and sass to counterbalance this.

Naoise Hardiman May scored my electro pop songs to quartet arrangements. Rather than choosing between baroque and sparse, we decided to have both – we got our Phillip Glass prone moments and our Disney thrills. Though I can’t read sheet music and have no idea what a semitone is, my ear and voice carry me, and I can sing the notes a particular instrument might play. Naoise produced an overall composition and then we worked together in my kitchen to underlay each verbal line with the correct tonalities – sometimes sporadic and anticipatory, sometimes blousy and camp, sometimes admonishing and dark.

And you filmed the performance with the quartet on 16mm?

I wanted to shoot the film at my studio: the place the songs were made alongside the paintings. We had recorded the audio in The Amadeus in London. I asked Patrick Hough, an Irish artist, to film the performance on 16mm on his Bolex camera. This was quite a madcap plan – given that the Bolex records 30 second shots with no sound, and would produce images without placement. I love the risk factor of using 16mm. The performance is put under a similar pressure to being on stage – you’ve got to get it right when the curtain goes up.

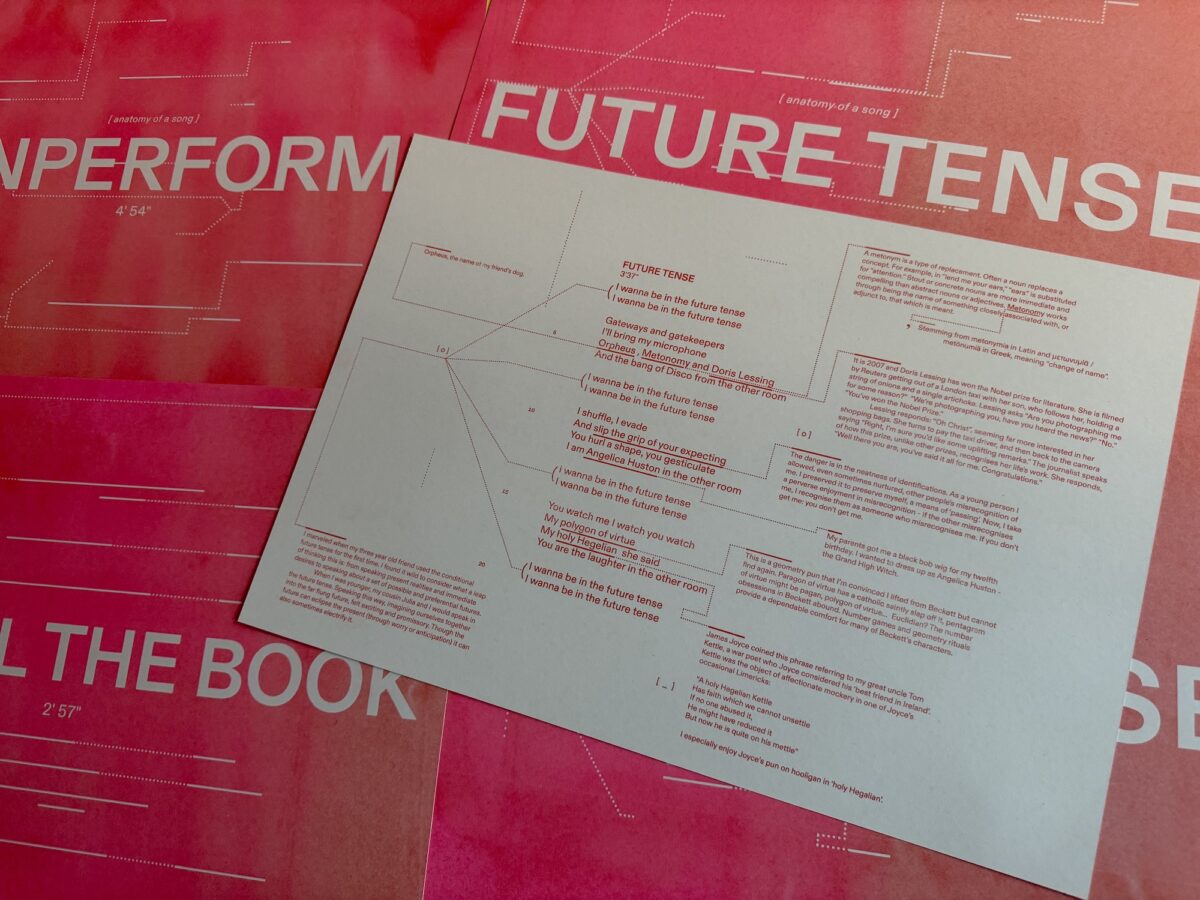

You’ve also produced “anatomy of a song” sheets to accompany the exhibition, though they are not explanatory. In this way, the viewer is not given any one explicit meaning andrather a diagram of your thought process…

Yes. As the songs aren’t conceived as linear meaning forms, it would be antithetical to talk about them in a “this song is about X Y Z” format. Like the paintings, they are networks of citation. As you say, the song anatomies are a way of giving a listener access to my process. I worked with Ben Mullen, an architect and designer in Dublin, to produce these song diagrams as risograph prints that the audience can take home. Particular phrases in the songs are unpacked, ranging from etymological underpinnings to personal anecdote and direct citation.

I wonder if you can speak to the lyric “the birds outside are singing an avant garde tune”.

That’s the first line of the exhibition title track, “I smell the book”. In the ‘anatomy of a song’ sheet, the note for this lyric reads: “It’s early morning, in Greece and I wander out of the bedroom through fig trees. I am rarely awake this early. The birds are singing, in Greek I presume, and the staccato melody sounds both ancient and incredibly modern. The natural appears composed, intentioned, staged.”

The centerpiece of the works in the chapel space is CRIOCH, a Gaelic word meaning “end”, placed in front of the altar, demarcating a metaphysical “border” made reality. Why CRIOCH? Can we dive in a bit to the meaning of it and the text from which it originates?

I get a real giggle from the way this word for “end”, crioch (cri- OCK) is so harsh and onomatopoeic in Gaeilge. It turned up in the Mount Stuart archive at the end of gaelic plays and, in this case, an elegy. If you think of the French equivalent, finis, it sounds like it would be accompanied by an elegant curtsy, whereas the Irish is much more final and brutal, reflecting some of the dark humour in Irish literature.

Placing this work in front of the altar also made me laugh. The way in which Catholicism came to rid Ireland of paganism is not dissimilar to the way in which Gaeilge was suppressed. Putting this work in this central position in the chapel speaks to that, as if to say: we’re still here.