Es Devlin to unveil landmark installation in support of UNHCR the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Es Devlin to unveil CONGREGATION, a new large-scale choral installation she has created in partnership with UK for UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency’s national charity partner at St Mary le Strand from 3rd – 9th October 2024. The work, curated by Ekow Eshun, has been developed in collaboration with King’s College London in partnership with The Courtauld.

Emma Cherniavsky, Chief Executive of UK for UNHCR, said:

We are honoured to be working with Es Devlin on this project and so grateful for her commitment and dedication to all those forced to flee their homes due to war, violence and persecution. Congregation is an incredible opportunity for refugee co-authors to share their stories with London in a new way. We are excited to see how visitors will respond and hope the installation will inspire more support for and solidarity with refugees here and around the world.

The work will be free and open to the public daily from 10am till 6pm with free public choral performances within the surrounding pedestrianised area of the Strand outside The Courtauld at 7pm each evening from Thursday 3rd October until Wednesday 9th October, to coincide with Frieze London.

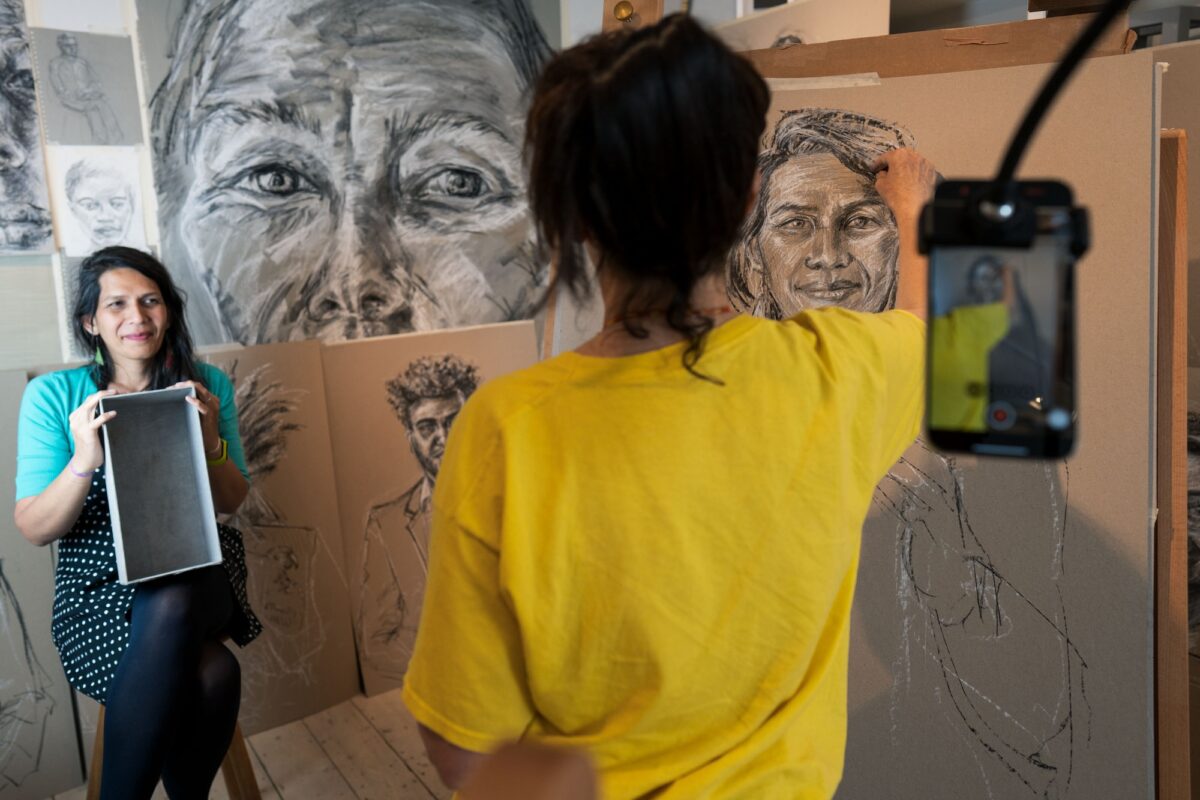

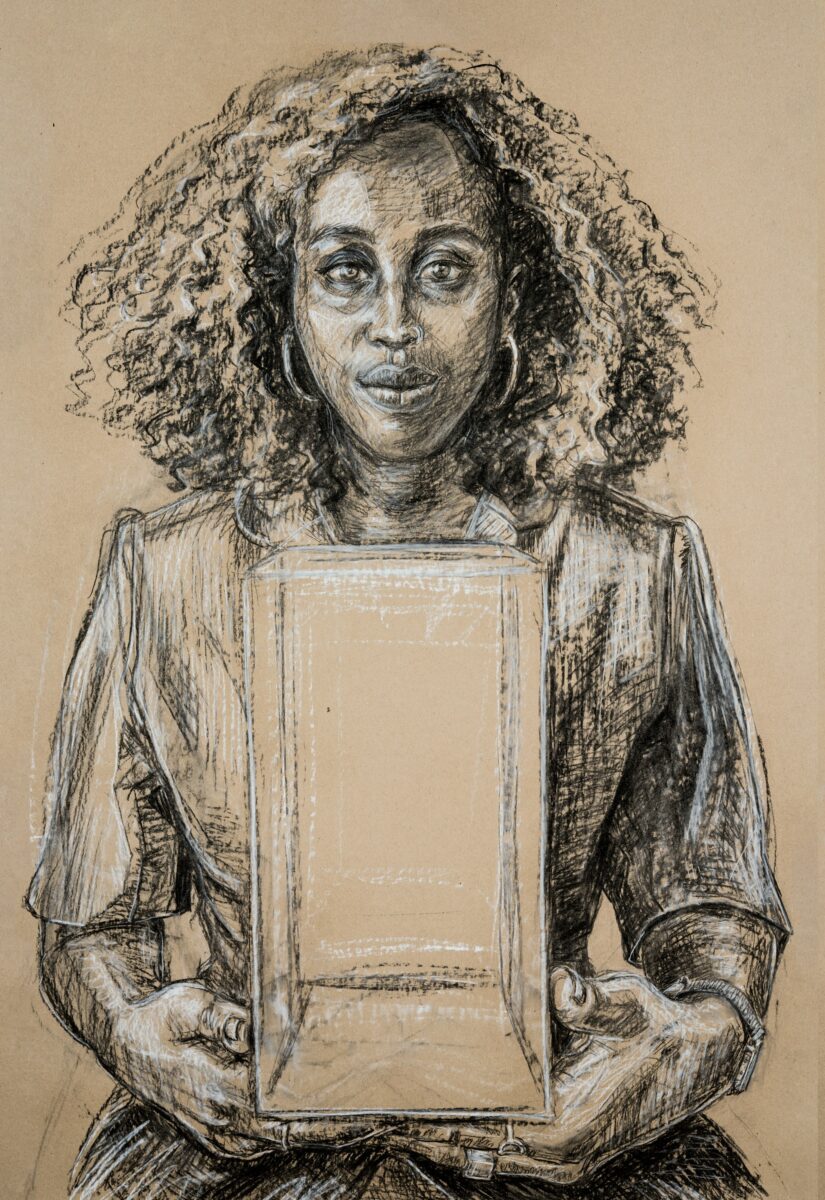

Over the past four months, Es Devlin has been making large-scale chalk and charcoal portraits of 50 Londoners who have experienced forced displacement from their homelands. The drawings will be presented as a monumental projection-mapped tiered structure within the eighteenth-century church of St Mary le Strand adjacent to The Courtauld and Somerset House. The sculptural collective portrait will be accompanied by choral music performed outside the church at dusk each evening.

Each portrait sitter is a co-author of the work. Each is depicted holding a box containing a projected animated sequence which they have envisaged. The co-authors constitute a vibrant London congregation whose roots extend across the globe to Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Yemen, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Palestine, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda, Somalia, Tanzania, Chile, Venezuela, Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo and Germany. All 50 voices are included in an accompanying sound sequence composed by Polyphonia. The projected film sequence has been created in close collaboration with film maker Ruth Hogben and choreographer Botis Seva.

In parallel to the installation, the Sanctuary Programme and The Policy Institute at King’s will be holding public events and policy development discussions with leading researchers on asylum and migration policy. These will be presented as part of a wider season, Lost & Found: Stories of sanctuary and belonging, developed and curated by King’s Culture.

Professor ‘Funmi Olonisakin, Vice President (International, Engagement & Service) King’s College London, said:

As part of King’s commitment to serving society, it is inspiring to see this visionary work by Es Devlin connecting so closely with our pioneering Sanctuary Programme, which promotes social justice and supports refugee students, as well as the work that The Policy Institute is leading around international attitudes to human migration. Societal impact sits at the heart of King’s research practice as does community engagement across London and internationally. The Lost & Found creative programme, produced by King’s Culture, will provide impact, engagement and visibility for these vital areas of enquiry

The work is being made in response to the history of St Mary le Strand, the first of 12 churches to be completed according to Queen Anne’s commission of 50 new churches to replace those lost in the Great Fire of London. St Mary’s Scottish Catholic architect James Gibbs practiced in secret at a time of severe persecution, weaving emblems of the exiled Catholic James of Scotland within the architecture of the building. The church is also replete with Masonic symbols and was the site of masonic gatherings whose secret congregation included both Catholic and Jewish members, in spite of public prohibition.

Devlin and curator Ekow Eshun are responding also to their research into the Courtauld’s origins, established by a Huguenot refugee, and the origins of King’s College London as a university with a long history of developing sector-leading initiatives that support forcibly displaced staff and student, as well as the Strand’s history more broadly as an ancient processional route from east to west, a foundational migratory artery of the city since AD93.

Professor Mark Hallett, Märit Rausing Director of The Courtauld, said:

This is a wonderfully ambitious and innovative project, and we are thrilled that is has been informed by Es Devlin’s experience of our extraordinary collection. The Courtauld is always looking to collaborate with today’s most interesting artists, and to stay true to our founder Samuel Courtauld’s ideal of ‘art for all’. It has been a delight to work with Es, and to see her remarkable vision for Congregation being fulfilled in such a spectacular way.

Devlin’s approach to making the portraits is rooted in a visit to Lucian Freud’s sketchbooks in the archive of the National Portrait Gallery, and in her research within The Courtauld’s collection of 500 years of portraiture from Albrecht Dürer to Frank Auerbach. She carries out the first 45 minutes of the drawing session without any knowledge of her sitter/co-author. After 45 minutes the drawing is paused while the co-author tells Devlin their story, then the drawing resumes.

Es Devlin said:

I was moved in 2022 by the generosity of spirit with which we, as a country and as individuals, offered support to those displaced by the war in Ukraine. I wanted to understand why we have not yet been drawn to show an equivalent abundance of support to those displaced in comparable circumstances from other countries including Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Eritrea, Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda and many more. I went to UK for UNHCR to learn more about the numbers and contexts of the 117 million people currently displaced globally, and the experiences of refugees now living in the UK.

I am beginning each portrait without knowing my sitter/co-author’s story. For the first forty-five minutes I am drawing a stranger: I am drawing not only a portrait of a stranger, but also a portrait of the assumptions I inevitably overlay: I am drawing my own perspectives and biases. I am trying to draw in order to better perceive and understand the structures of separation, the architectures of otherness that I suspect may stand between us and the porosity to others that we are capable of feeling when these structures soften.