Last year marked half a century since Robert Smithson’s untimely death. Now, the canon’s revisiting his legacy in a new way. “Teresita Fernández / Robert Smithson,” which just unveiled at SITE Santa Fe, is the first show to place Smithson in conversation with a contemporary artist. Fernández’s sculptures and installations belie an intimate passion for her earthen materials, like graphite, charcoal, and ceramic, with which she parses the ephemeral relationship between humans and the land we live on. In a sense, Fernández has advanced the mantle from Smithson. But, she also draws from land art practices predating his association with the term.

Fernández, who’s studied and spoken about Smithson, co-curated the show with Lisa Lefeuvre, Executive Director of the Santa Fe-based Holt/Smithson Foundation. Their efforts confront Smithson’s legend head-on. The show’s first room offers the first of three films throughout, a 35-minute documentary on “The Spiral Jetty” (1970) that demystifies his most fabled work.

A satisfying symmetry asserts itself straight away. Two sculptures, one by each artist, anchor that first room—side by side, each with a wall-mounted piece behind it. Small works on paper and panel by both ring the walls surrounding the other’s sculptures. Smithson’s “Road to Crater” (1969)—a map he drew as an early proposal for an unrealized earth work at a malachite mine—hangs feet from Fernández’s “Viñales (Reclining Nude)” (2015). Its angular arrangement of Wakkusu concrete, bronze, and malachite sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo compares Cuba’s verdant Viñales Valley UNESCO site with the luxuriating feminine form.

“Both artists were really interested in the way the movement of capital and materials is so fundamental,” Lefeuvre told me. “What does it mean to get malachite from the Democratic Republic of Congo? What does it mean for Smithson to work with this material 50 years before?”

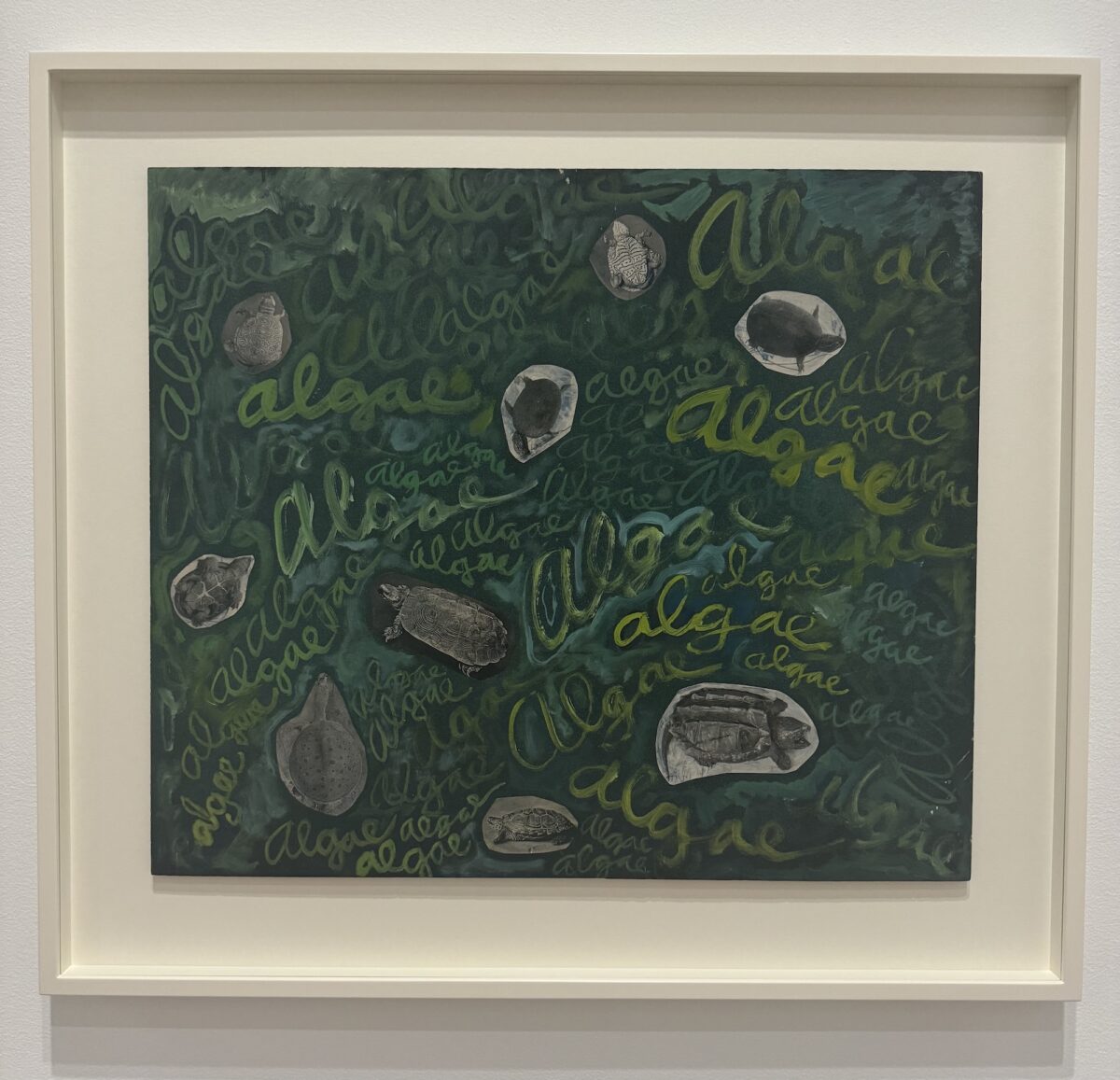

In the late 1960s, Smithson illustrated the dichotomy between materials’ original homes and their endpoints concretely his “Non-site” artworks, which spanned sculptures and documentary photographs within a single work. “Non-site (Franklin, NJ)” (1968), replicates the stacked architecture of “Viñales,” except on the ground, in a pyramid of five open bins full of limestone from New Jersey. It was part of the critical 1968 “Earthworks” show at New York’s Dwan Gallery.

An elemental structure also takes shape throughout the show’s circuit of seven galleries, leaving a few compelling ambiguities along the way. The show’s back-nost room feels like it should be the climax, with Smithson’s iconic “Mirrors and Shelly Sand” (1969-70) and Fernández’s “Drawn Waters (Borrowdale)” (2009) emerging from “Sfumato (Epic) 2” (2024), but this show’s made of many climaxes, evoking the un-idealized, awe-inspiring authentic nature that both artists admire.

Scores of Smithson’s drawings hold their own amongst all these spectacles, on a rare outing from the Holt/Smithson Foundation. Some of these small works are studies, like “1,000 Tons of Asphalt” (1969). Others, like his mixed media collages, colorfully restore playfulness to his memory. 12 zodiac illustrations that Smithson made shortly after returning from Rome in the early 1960s are a standout. They’re entertaining, whimsical, and have never been shown before.

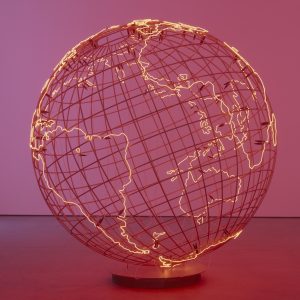

Smithson’s early fixation with religious imagery has been the subject of recent discussion. Lefeuvre classified the artist’s expansive body of drawings and paintings depicting Christ’s crucifixition as part of his wider interest in “belief systems,” part and parcel to the modernist, humanist framework for understanding the world, comingling dogmas suchas astrology and christianity with contemporary religions like the worship of clock-based time and cartography.

Both Smithson and Fernández have devoted themselves to unraveling such maps, to unearth the territory beneath. Surrounded by a site-specific recreation of a 2013 charcoal installation by Fernández, SITE Santa Fe is displaying footage a lecture Smithson gave to architecture students in Utah during 1972 about a dilapidated hotel he explored on the Yucatan peninsula.

For the first time, this show screens the Q&A afterwards, where Smithson’s affinity for entropy waxes antiimperialist. “Smithson is really interested in undoing the romanticization of ruins, undoing the myth of the picturesque, undoing the idea of landscape and the representation of landscape being all about a bucolic, pastoral, British idea,” Lefeuvre said. In the years before society started getting wise to climate change, the interconnectedness of ecosystems, and the need to consider humanity part of nature—not separate from it—Smithson was writing that “The farmer or engineer who cuts into the land can either cultivate it or devastate it” for Artforum.

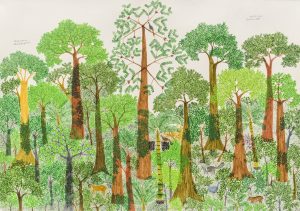

Smithson is also credited with pioneering conceptual and installation art as we understand them today. Fernández has alchemized his efforts in this arena for a new era. The most immersive of her works in this exhibition are concentrated in its second room, to the right of its first, which honors the cosmos. “Ink Sky 2” (2011) suspends bits of glittering Galena rocks overhead. The sprawling “Carribean Cosmos (Earth)” (2023) tesselates rich glazed ceramic into a mesmerizing weather scene. Two haunting “Dark Earth” works from 2023 draw viewers into their thickets of celestial embellishments. This is the same room where Smithson’s zodiac drawings hang. Here, and throughout, Fernández demonstrates how material maximalism enhances Smithson’s aims.

She and Smithson even levy rather similar criticisms. Fernández has challenged the type of legend that art history has ascribed Smithson, as the progenitor of land art. “It’s indicative of the kind of bubble that the art world somehow feels very comfortable in,” she told Artnet News.

Smithson, too, decried that bubble in his scorn for object fetishism. Subjecting his art to the elements meant nature had agency. However, galleries remains necessary venues for art. Much like the red herring beauty of Fernández’s artworks lures viewers into the challenge beneath their surfaces, this show’s visual thrills allow it to transcend that bubble by encouraging slow, exciting, active looking. “Teresita Fernández / Robert Smithson” proves conceptual and installation art weren’t invented to sound smart. They are the cumulative effort of centuries. They are intended to have an impact, to shape and show how we move through the whole wide world.