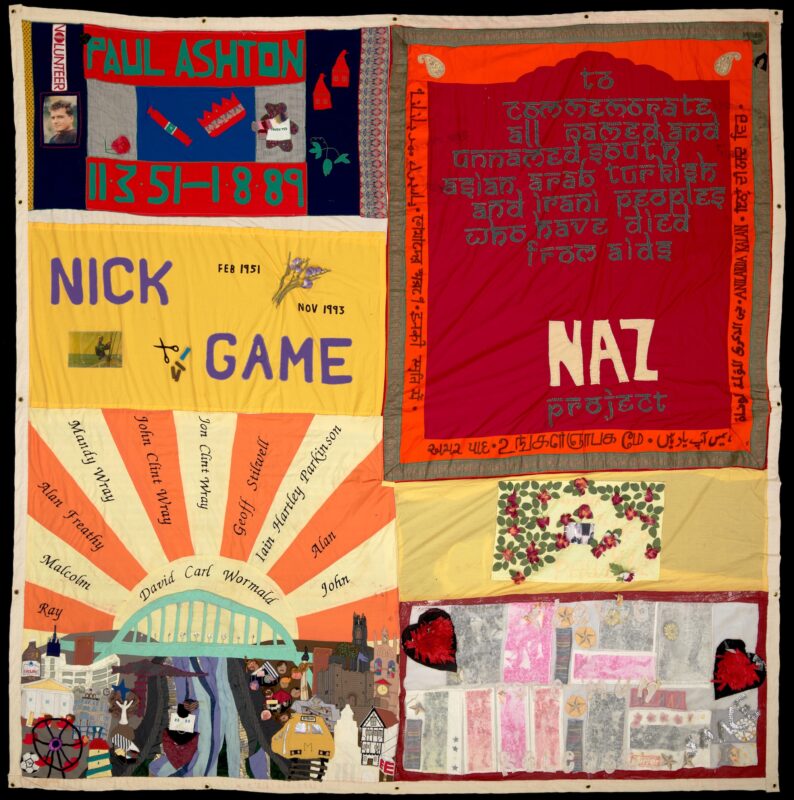

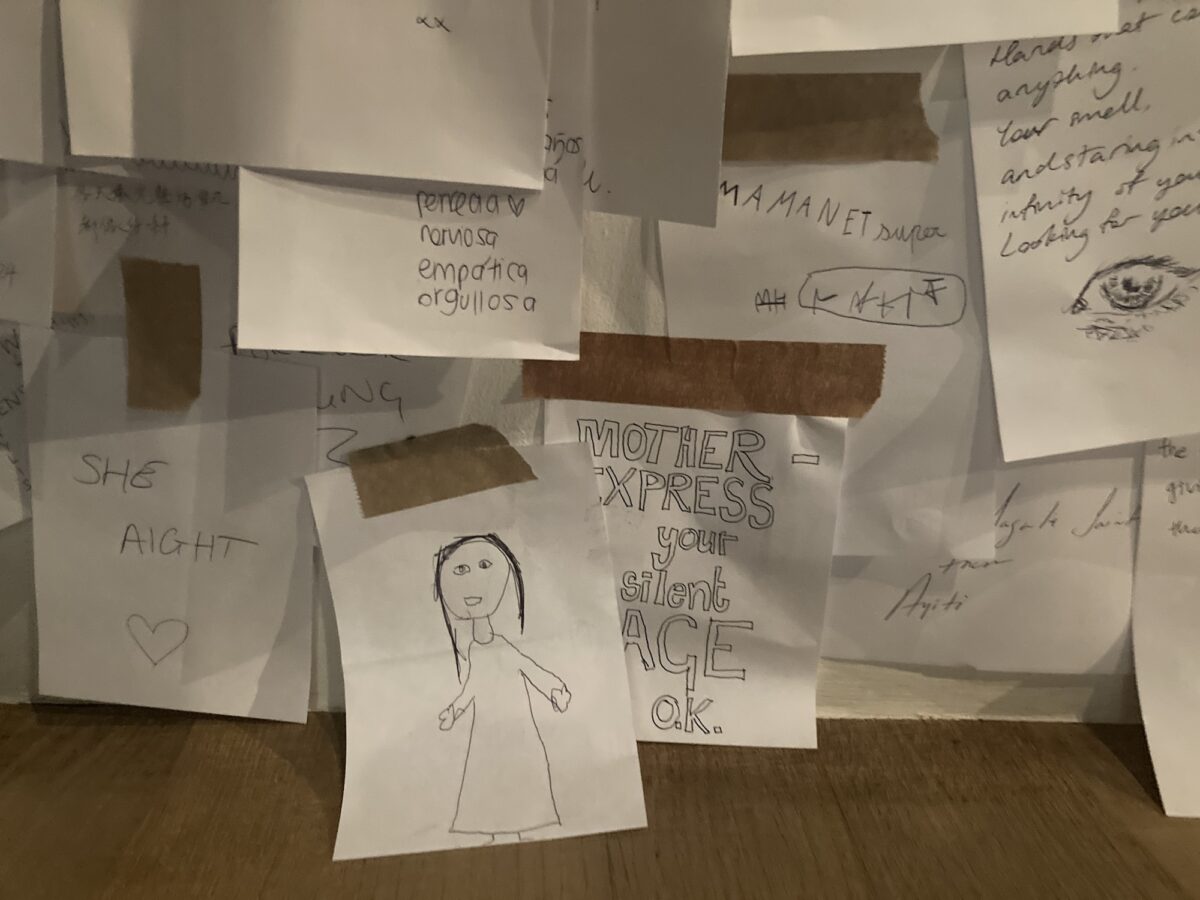

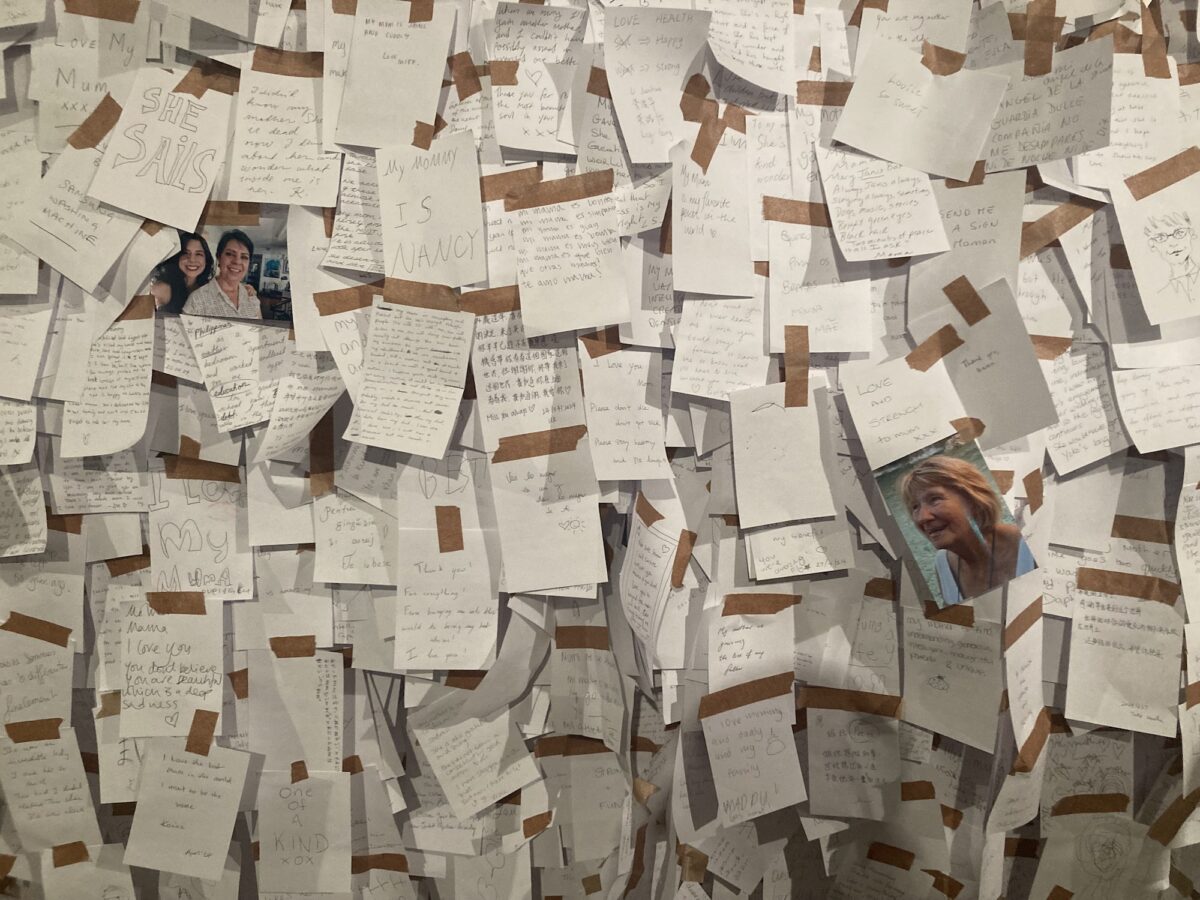

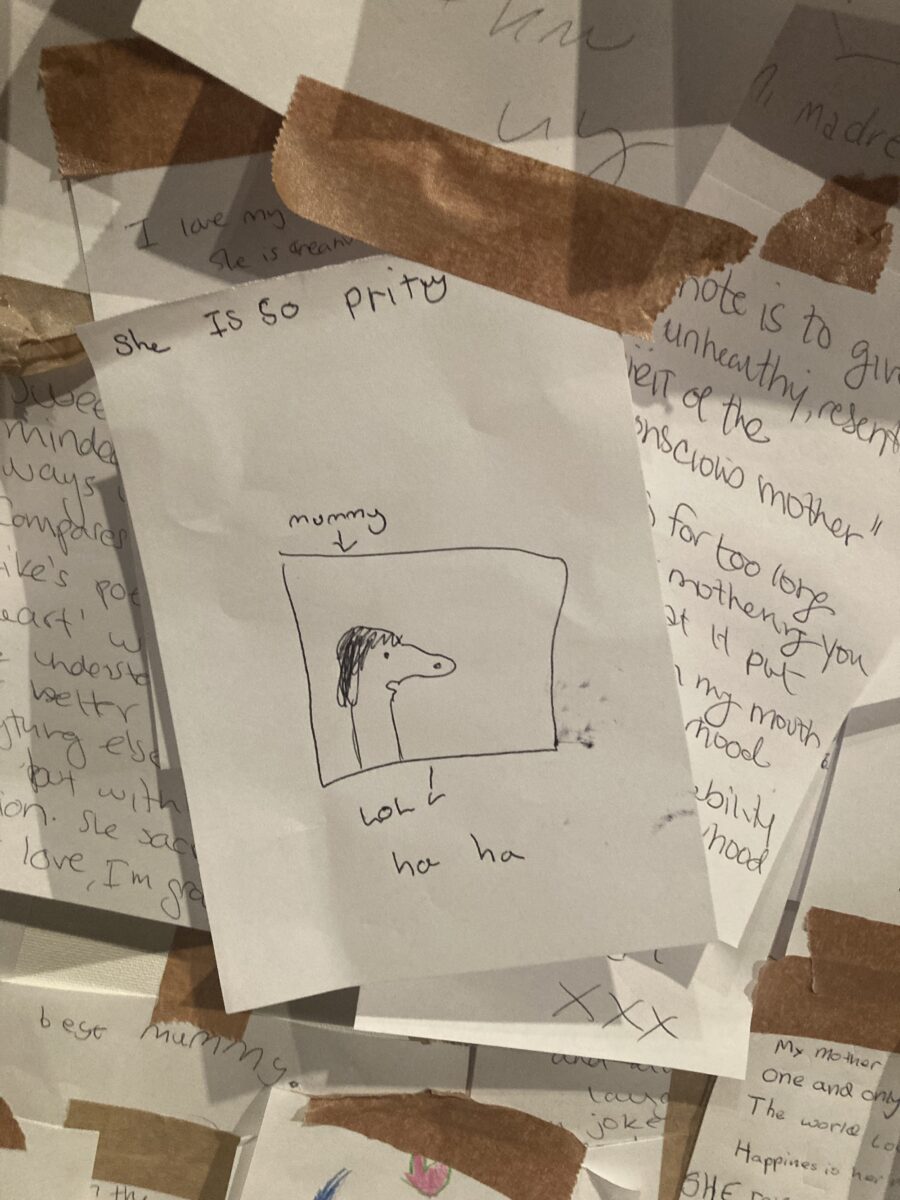

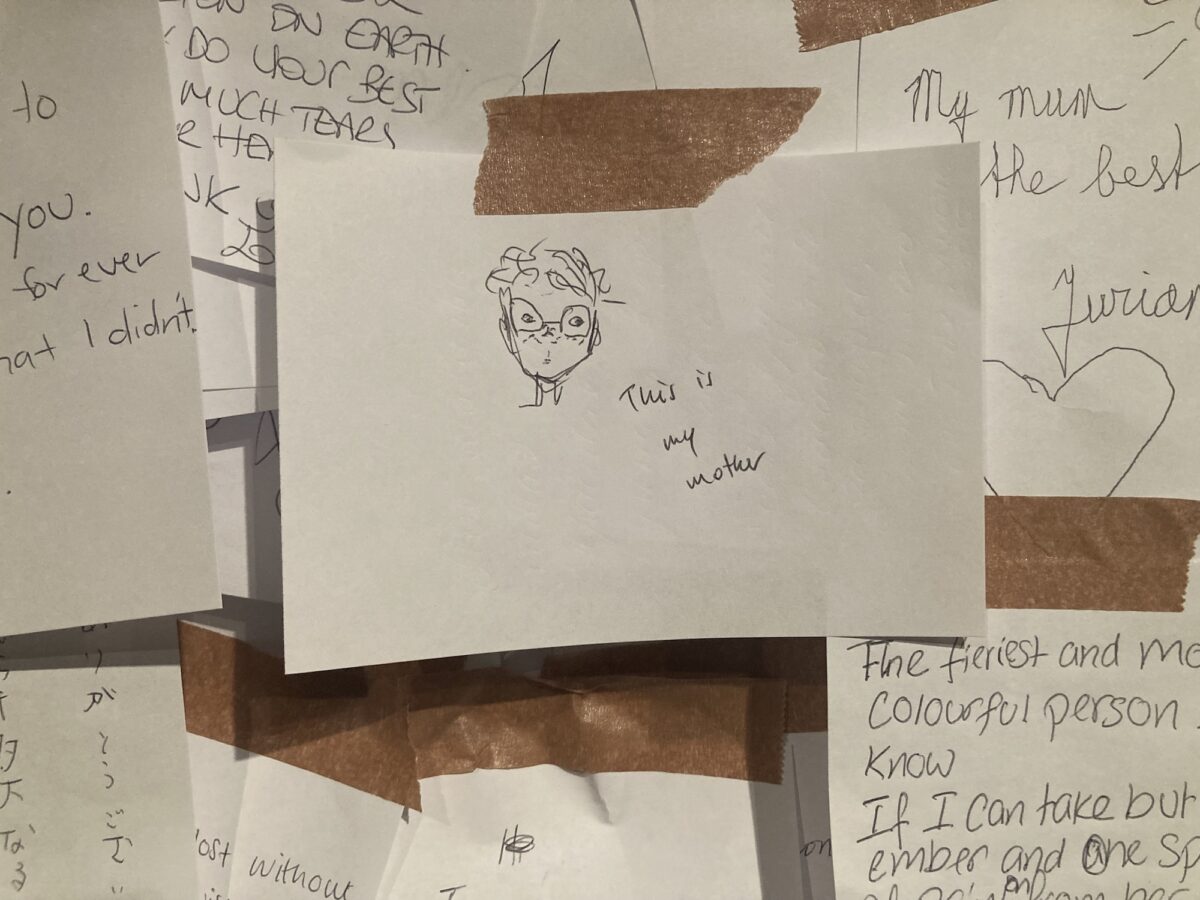

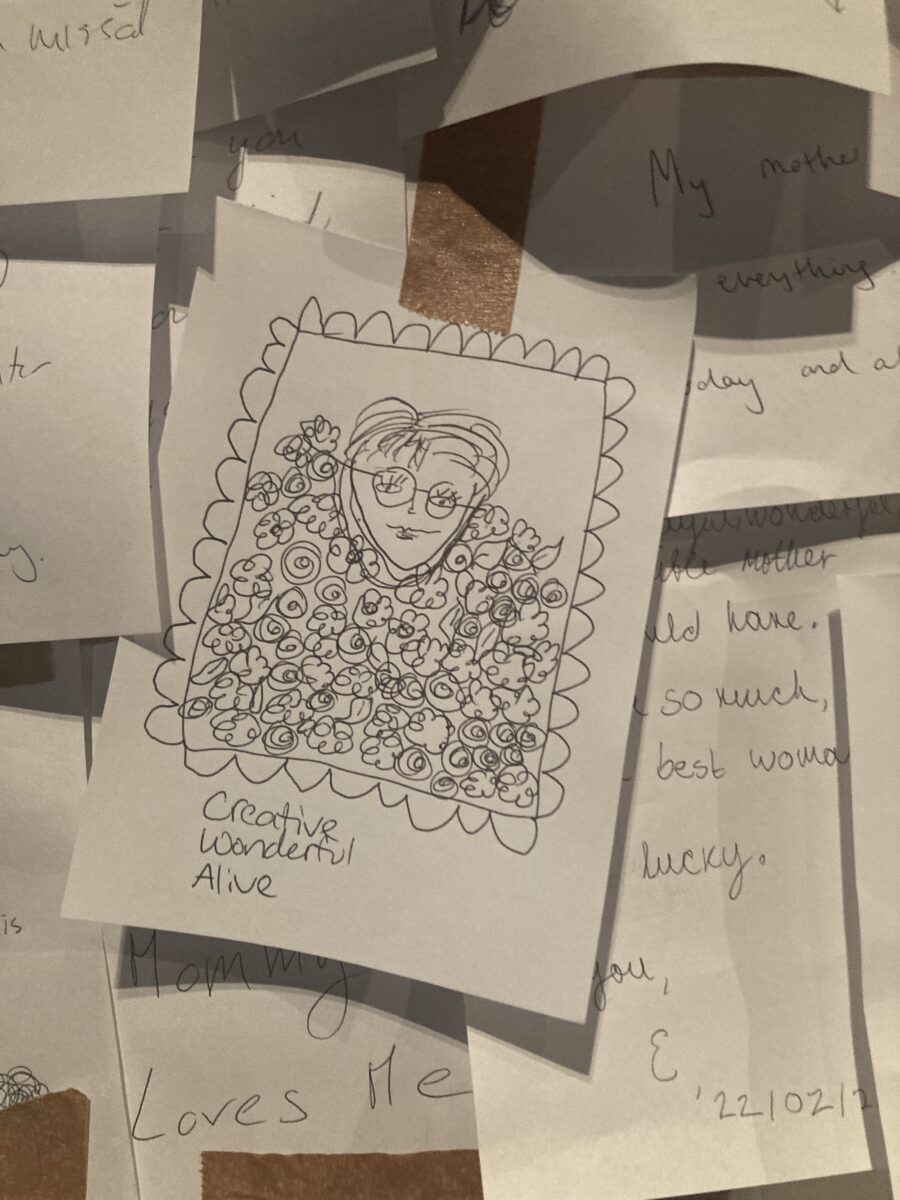

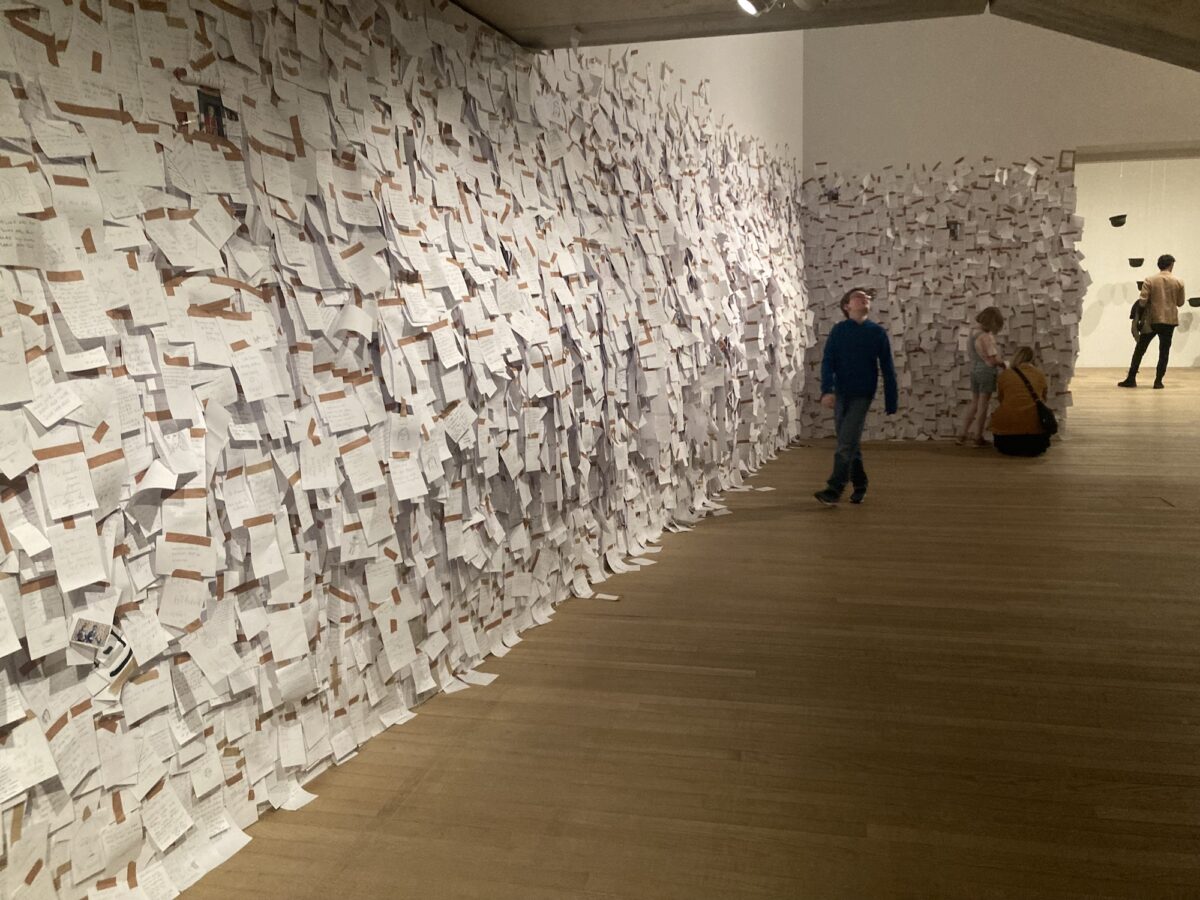

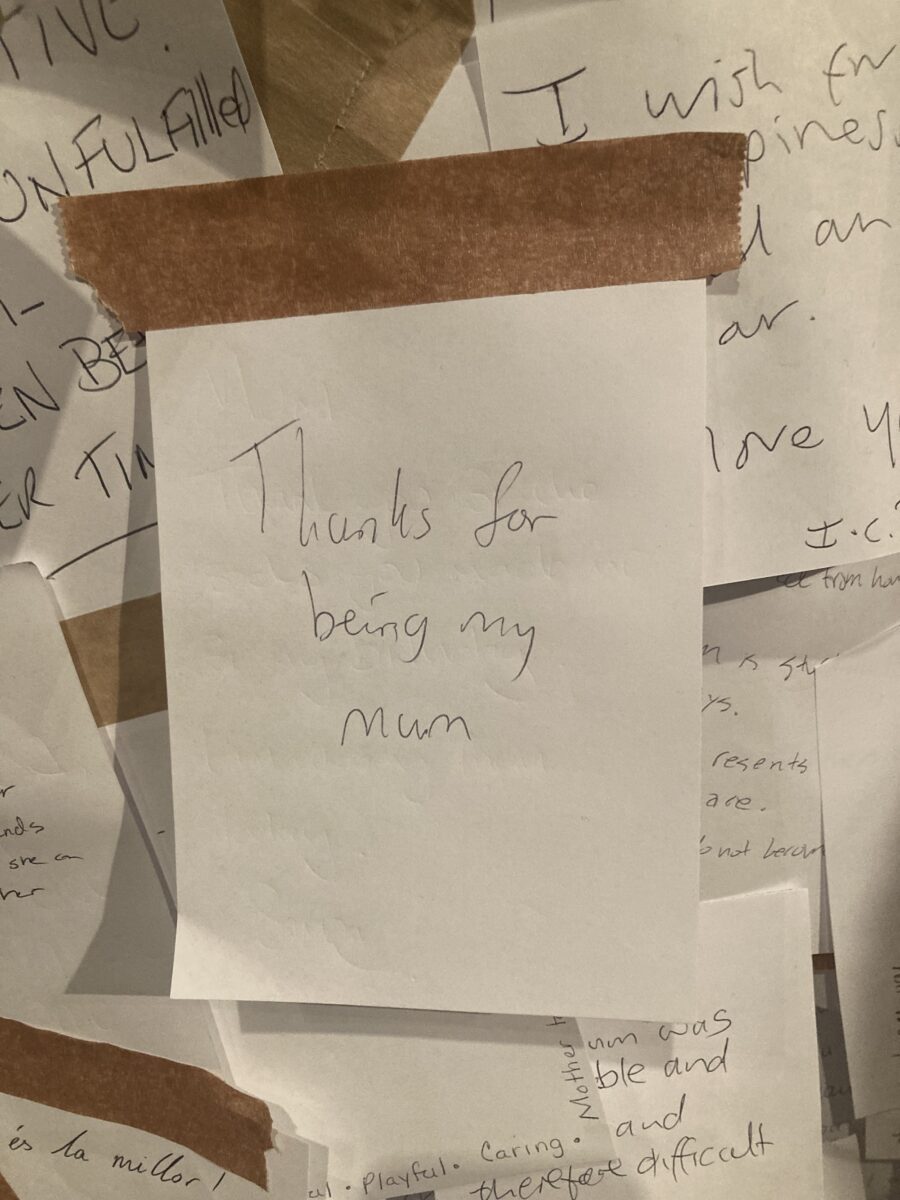

Lying on the floor of Tate Modern, I consider — at Yoko Ono’s bequest — the complicated and carnal affection inherent to the relationships shared between thousands of strangers and their mothers. Hand-written messages taped on top of one another comprise a ruffled swell that sags from the wall like a pregnant belly.

Some are wholesome, others wrought with complication. They are all cathartic. In the distance the artist is belting out sounds that can only be described as something in between a shriek and a moan. Next to me, an elderly man weeps softly.

Ono’s retrospective, Music of the Mind, feels like a regressive rollercoaster. Partly thanks to the nostalgic nature of the content (including an irresistible array of charming doodles), its formally biographical curation (confirming that her most important work really did happen when she was still single), and the force of the persona that is Yoko — but also thanks to Ono’s continual prompts for participation, which impose not only a physical but also a social and emotional toll on the visitor.

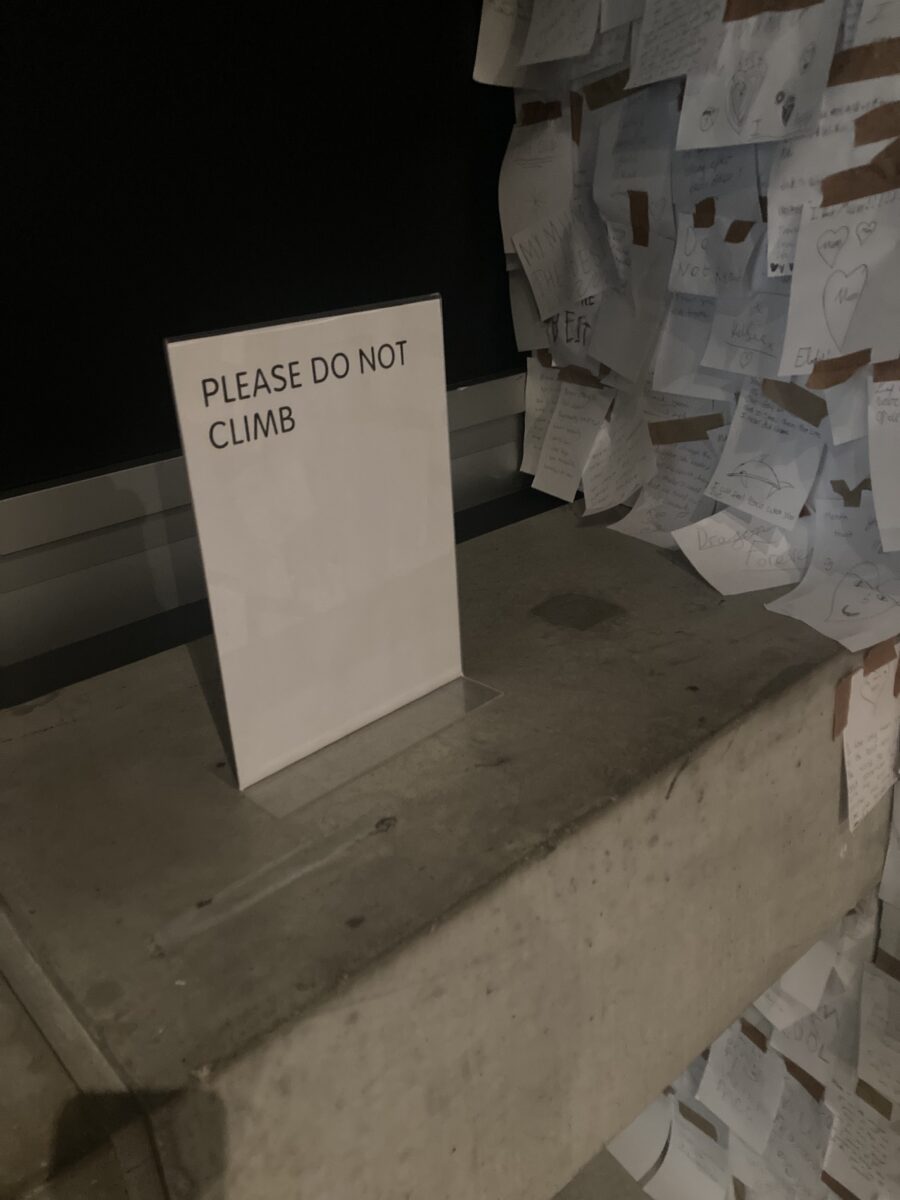

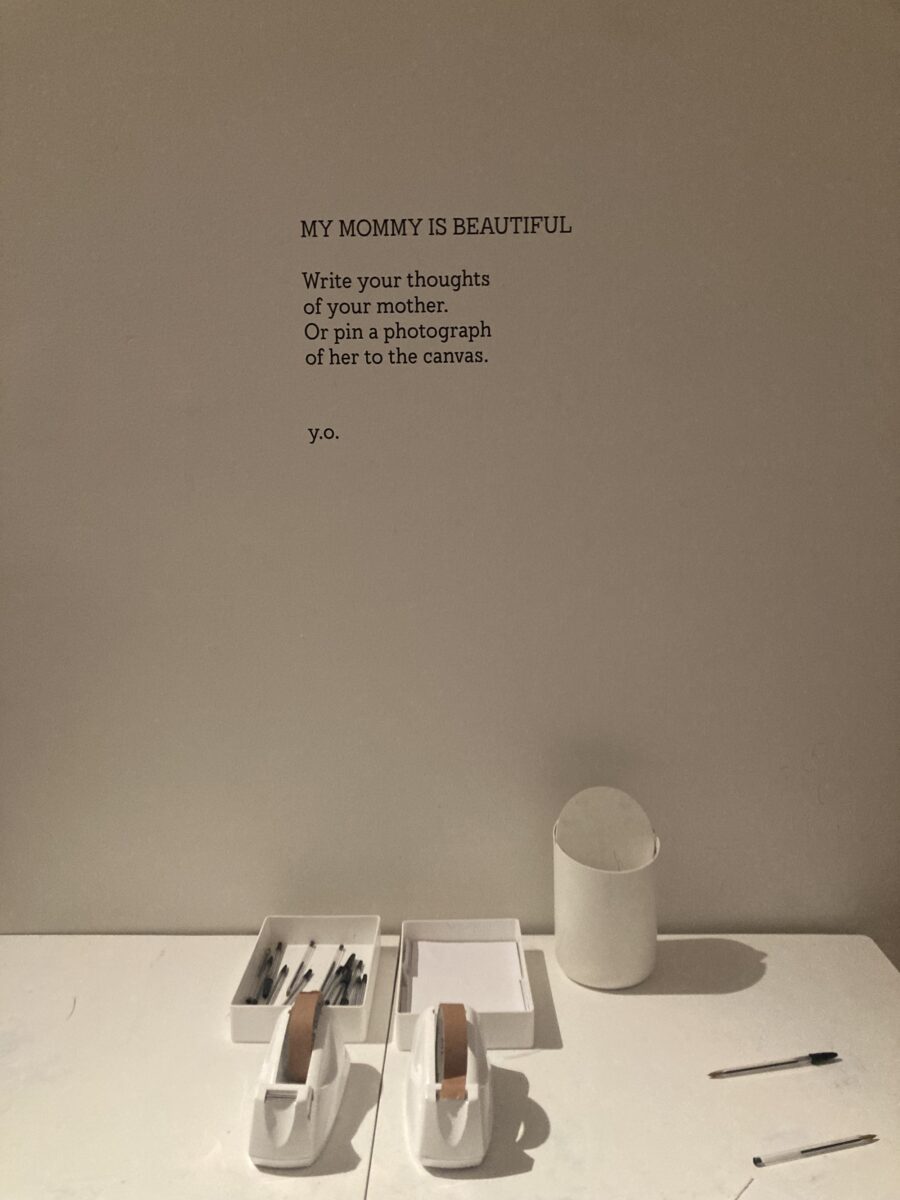

Throughout the galleries, we encounter a series of procedures. Ono outlines instructions that are vague but succinct: Hammer the nail. Trace your shadow. Write your thoughts about your mum and stick it to the wall. What’s most interesting is how the audience — when given an inch — takes a mile.

Compelled to break free from the format, museum-goers have taken the invitation to push the envelope, so much so that the curators have installed a retroactive no climbing sign. In the Add Color (Refugee Boat) room, multiple visitors stop in front of one particular message scrawled at least eleven feet off the ground just to discuss how someone managed to even get it up there.

I might not usually invite myself to lay on the floor of a museum, but it’s actually the third time over the course of the installation that I have been allowed to do so. In this way, Ono’s participatory pieces are like a gateway drug: the more we engage with them, the farther we regress from the behaviours typical to an otherwise predictable and all too often stagnant institutional setting.

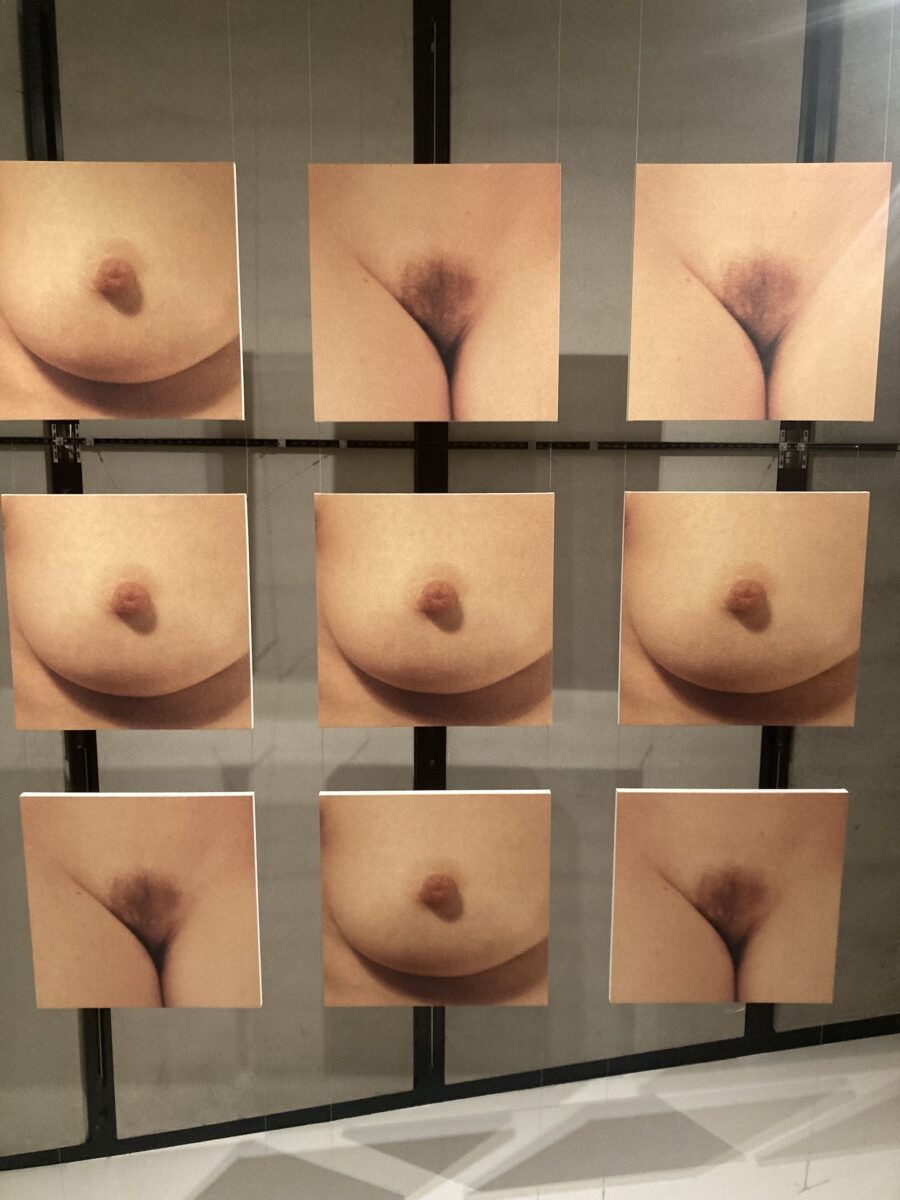

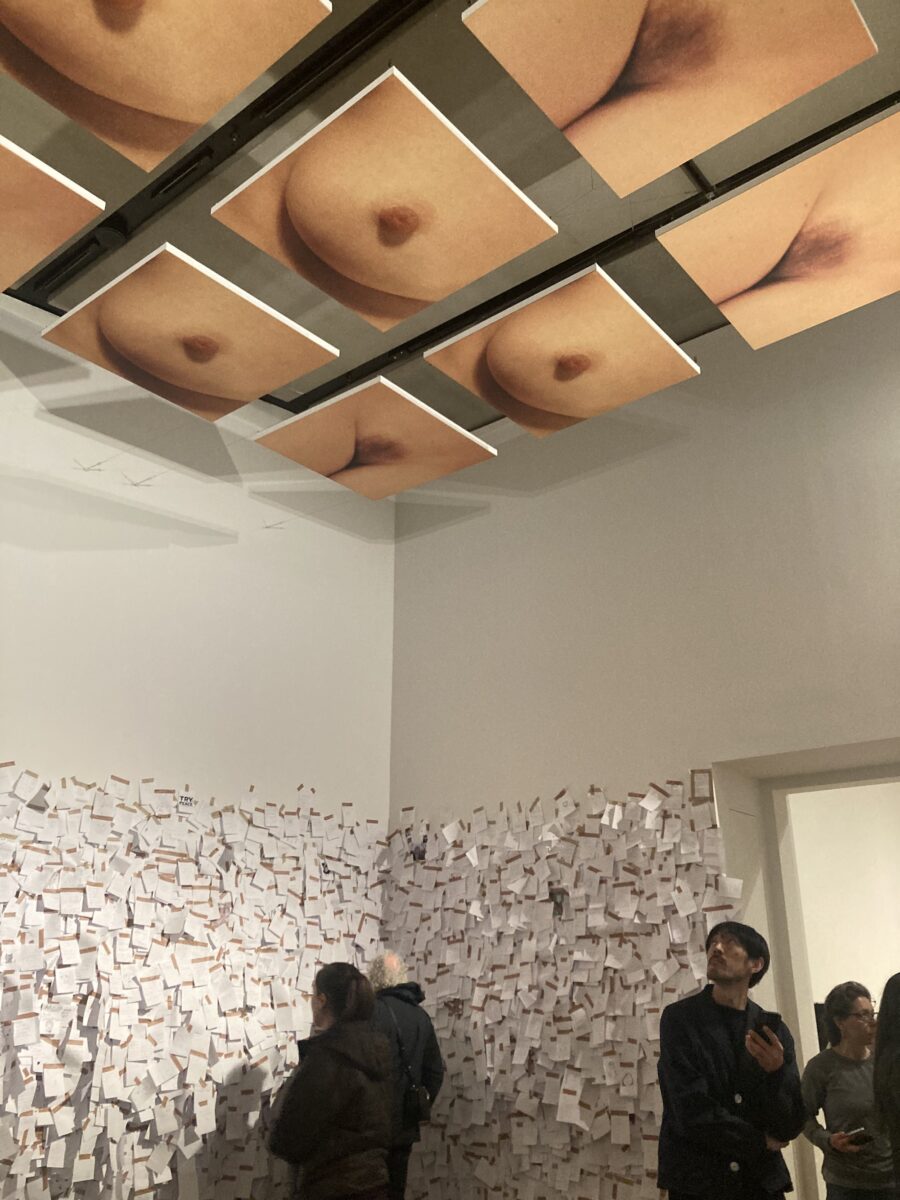

I’m lying down to photograph pictures of female breasts and pubis mounted on the ceiling. Baring the caption ‘My Mummy Was Beautiful,’ the same pictures first covered the ceiling at the gallery of Tate Liverpool in 2004. Banners of the images were also plastered around the city. According to Tate’s archives however, reception from locals was “less than positive”.

Tate doesn’t say why Liverpool’s reception was poor, but the apparent mastophobia is just one example of double standards in the creative industries, especially considering the city’s recent positive reception of A Game of The Mind, a Liverpool-based treasure hunt-style project created by Ono but John Lennon-themed.

This kind of double-tracking is pervasive not only in the arts but also the music industry and pretty much everywhere — though interestingly enough, not in the city’s exotic fish trade. According to city ordinance, in Liverpool it is illegal for a woman to expose even a single breast. However, women bearing their chest are exempt from prosecution if they work as a clerk in a tropical fish store.

Nudity and absurdity aside, Ono herself cannot — to this day — escape her proximity to Lennon — nor does she want to. She also has not escaped her association to the accompanying rhetoric that cites her as responsible for single handedly breaking up his band — a narrative whose time is ripe for retirement. Many lament the loss of the Beatles but few ever bring up the fact that Ono’s career was also hijacked.

In any event, the seemingly more positive reception of the exhibition in London may have more to do with the span of two decades than with the city or even the Beatles. In the age of social media, the weirdly public yet anonymous opportunity to reveal intimate mommy messages makes a lot more sense. Furthermore, against the backdrop of prolific data collection, participation has become an integral part of the neoliberal feedback loop ever more present in our day-to-day lives.

Participation — particularly in a written form — has become part of contemporary existence in a way with which early 2000’s audiences were not familiar. Performance art has also changed. In the 1960s, audience participation was an act of subversion — it was avant garde. Today, it has become the duty of the consumer and the final way to validate a transaction, commercial or otherwise. Just think of the last time you were asked to fill out a survey.

Notwithstanding the privacy paradox — that is increased privacy awareness paired with the dynamic of over-sharing one’s innermost thoughts — perhaps the impact of Ono’s piece has a new context in which to exist, and this time flourish under new circumstances. Ono’s piece has not changed, but the permits of regression have.

The parallel proliferation of wellness culture, growing mental health crisis, and unprecedented defunding of the NHS services in the UK together create a perfect storm that leave the public ready to open up. As much an adult daycare centre as it is a a place to see art, the behaviours in this newly created space facilitate redefinition of the museum as an institution of retreat, regression, and even healing.

Regression can be a beautiful thing. It’s not everyday we truly have the opportunity to do so, especially not in any kind of public or institutionalised way. Save for the confines of a psychiatric sofa, society rather encourages us to progress; to develop, move forward, and expand upwards instead of downwards or inwards.

With an incentive to create works that are contingent upon an audience’s presence for their completion, Ono refutes traditional notions of artistic authorship and autonomy. Beyond these requests are also cached creative opportunities to perform under one’s own parameters, and even to use them as an opportunity for inner psychological exploration.

As I visited the exhibition in April and it runs until September, I only have one question: will the structural integrity of the wall of messages bare the weight of thousands more?

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern until 1st September 2024: tate.org.uk

All photos © Camille Moreno