The newest UK solo show since decades by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare CBE RA hasn’t even officially opened yet when an associate leans into his ear and tells him that The Guardian has already given Suspended States the publication’s top rating of five stars.

Around him, a frenzy of journalists eagerly queues up as others mill about the Serpentine’s peripheral galleries, photographing a collection of chromatic sculptures, textiles, a dollhouse-sized city of refuge spaces, and a “war library” of historical conflicts and peace treaties, each book dressed in a bespoke sleeve designed by the artist.

Non-reactive at first, he takes a moment to process the information.

“It just makes me giggle when I read the stars,” he says as the corners of his mouth curl slightly. It seems that flattery and internet points mean little to the artist, whose energy is rather spent endorsing the Yinka Shonibare Foundation, which supports international exchange and cultural infrastructure between the UK and Nigeria through residencies, collaborative opportunities, as well as educational & research projects. Everything he does stands in the face of residual colonial transgression and says, not today. Not in our globalised world. We can do better.

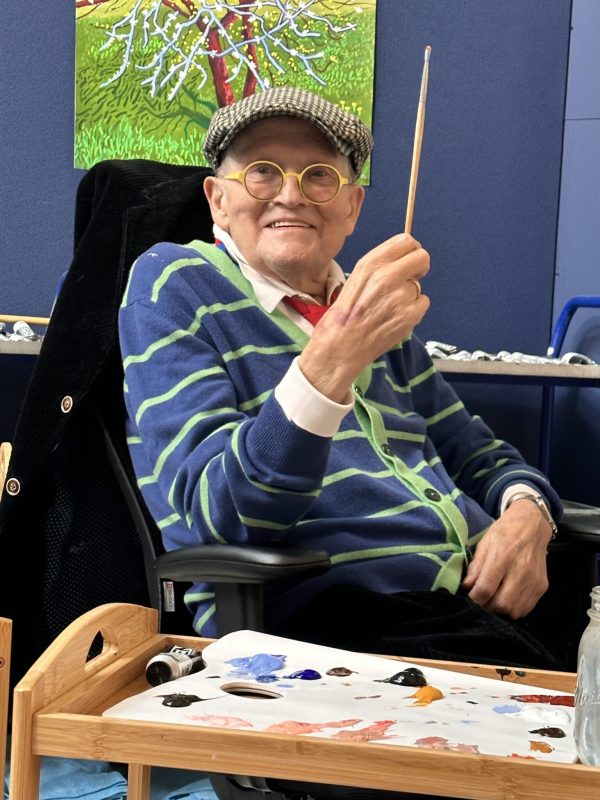

Like the eye of a storm, Shonibare himself is a picture of calm. Obliging a selfie with a young fan, his smile radiates. When you ask him a question, he looks you directly in the eye, his presence self-effacing, thoughtful, and positively serene.

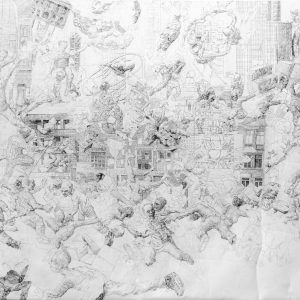

In the next room, Shonibare’s sculptures encapsulate his stoic demeanour. Pacifist but not passive, he has produced his own response to the post 2020 revisionist purge of problematic public statues that glorify war mongers and slave traders. But instead of chucking oatmeal at them or submerging the problem in the canal, Shonibare proposes a more whimsical and invariably penetrating strategy: he asks questions.

We were able to sit down with him on the occasion of the opening and chat about the exhibition, his motivations, and what his foundation means to him.

Camille Moreno: Can you talk about the title?

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States is a way of saying that it’s work that kind of moves beyond boundaries, beyond binary oppositions like good and bad. Then also, keeping things in a state of suspense. Recently there’s been a lot of “you’re with us or you’re not with us,” very divisive ideas, particularly around social media. I’m saying that things are so much more complex, that there are kinds of grey areas.

Can you talk about the use of textiles?

So, I trained as a painter. I think it’s more common now for artists to use textiles in their work. At the time, it was actually considered “low culture,” and it wasn’t considered as important as painting. When I was looking at issues of identity and exploring African textiles, although I was trained as a painter I decided to abandon paintings — just to make a point by making my art out of that.

What surprised you during the making of the exhibition?

My initial proposal was actually for a film. The show was also supposed to happen much earlier, but then the pandemic happened and I couldn’t direct the film anymore. So that’s when I got the idea for the sanctuary city, so I decided I would do that instead.

What has been an unexpected source of inspiration?

Travel and visits to other countries. I have very strong memories of trips to places like Hong Kong — places that are out of my normal [environment]. I like nature — landscapes and farms. Particularly Nigeria as well. When you go out of the city, the landscape is kind of jaw-droppingly amazing. Especially on our farm that we have there for residents. The house we built for the artists is on top of a hill, and you look into this kind of forest of palm trees and it is…simply gorgeous.

The sanctuary explores the notion of a refuge. Where is your refuge? Is it a physical place?

At our studios where we work, at the end of my garden I have a small studio where I go to do my thinking. So that’s actually very good, and I don’t have to be with my whole team. I can focus and do my sketches and come up with ideas. There will be birds singing, it’s very lush and green. I think that would be my refuge.

What motivates you to support other artists?

I have had a lot of opportunities, and I have been fortunate to have the level of success I have. I’m in a position to support other people and I decided in 2008, when I acquired my studio in London, to create guest projects and allocate half [the studio] as a project space for artists. I felt that many artists don’t have a space to show their work or to even make work, so I make that space available to them and that then evolved into the foundation.

I have a studio practice and I also have a social practice. The work of my foundation is to actually create friendships between people. To understand that the conflicts in the world are based on not knowing the other and the fear of the other. We have a responsibility to get to know each other, to develop creative projects together.

Can you talk about the influence of literature and post colonial text in your work?

As someone of African origin, my identity is very much part of that colonial history. My identity is informed by that colonial history. I read a lot about colonial history over the years: Frantz Fanon, Joseph Conrad, Onibaba, Edward Said, the list goes on and on.

What is the role of the artist?

As an artist, I actually don’t have the answers. All I have is questions. We know the state of the world right now. We understand the refugee crisis. We see the centuries of war until now. As an artist, my work is to transform tragedy into beauty. I have no other way of approaching the most pressing issues of our time, other than to make social interventions.

Through my work, I wish that the world could actually be as beautiful as the work of an artist. The artist, in my own case anyways, is an idealist. I always wish that the beauty I create in my art can also flow into the world.

Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, SUSPENDED STATES, 12th April – 1st September 2024, Serpentine South