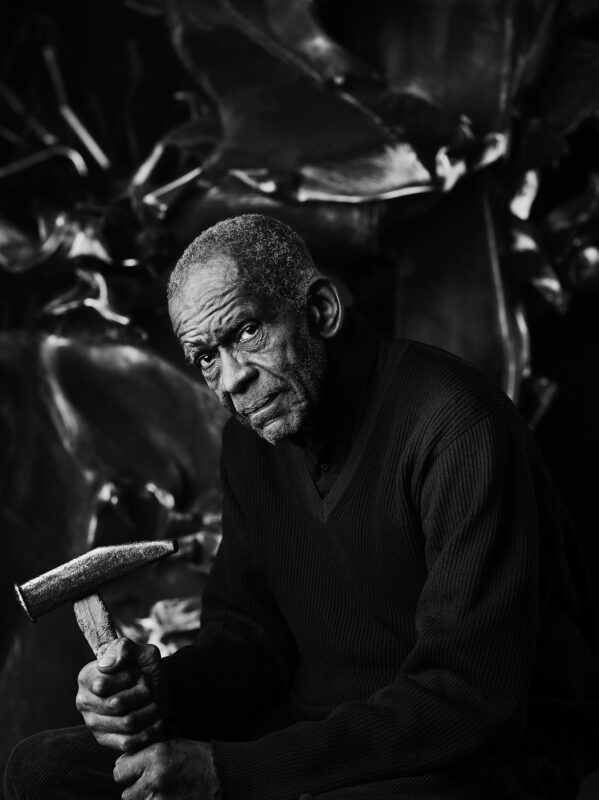

Richard Hunt’s first major exhibition in New York in over 50 years- Honouring the life and legacy of American sculptor Richard Hunt (1935–2023), White Cube New York is to present ‘Early Masterworks’, an exhibition bringing together 25 of the artist’s seminal sculptural works created between 1955 and 1969 – a fertile and critical period during which Hunt innovated the material techniques that would remain central to his prolific seven-decade-long career, immortalising him as one of the foremost sculptors of the 20th and 21st centuries. ‘Early Masterworks’ marks the largest gathering of Hunt’s works in New York since his landmark solo retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971.

‘It is an immense privilege to present Richard Hunt’s work at White Cube New York, with a nod to his important MoMA retrospective in 1971. At the age of 35, Hunt was the youngest and first African American artist to receive this honour, and over fifty years later, it feels very special to commemorate that historical moment. Hunt was a giant hiding in plain sight for decades, and with Early Masterworks, the first exhibition since his passing last year, we not only look forward to showing his powerful early sculpture, but also celebrating his life and art.’

Sukanya Rajaratnam, Global Director of Strategic Market Initiatives

In 1953, after receiving a scholarship at the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), Hunt encountered the work of Spanish sculptor Jose González, whose metal welding techniques profoundly influenced the young artist, providing him with an innovative means to cultivate growth and renewal through the deft handling of unyielding metal. Utilising materials salvaged from alleys and local scrapyards in Chicago, Hunt began to apply his sculptural practice to reconciling the natural and the industrial, employing his self-taught welding technique to create fluid, organic forms suggestive of biomorphic growth. In a statement from 1957, the artist, at just 21 years old, expressed, ‘I hope the resultant constructions exhibit an organic presence of life which the use of vigorous technique is designed to create. […] It is not possible to set down a clear outline for future work, for it seems that each new work suggests another either isolated in style and idea or as a developable series. I can only say that at present I wish to treat my materials (steel and space) in increasingly expansive terms.’[1]

Through metal, Hunt engaged in an iterative process – trialling, refining and rearticulating thematic threads, techniques of expansion and trajectories of metamorphosis. While early explorations included a fusion of metal and wood, as realised in works from his 1956 series such as Construction D, Construction N and Construction S, he later devoted himself exclusively to working with metal. These early masterworks are distinguished by characteristics located within distinct series, which equally overlap, build upon and engage in a dialogue with other works – from those rooted in classical and mythological themes and early 20th century Primitivism, to expressions of linear-spatial expansion, moving into the latter half of the 1960s towards more monolithic and enclosed forms, as exemplified by Figure Form (1966) and Stretch (1969).

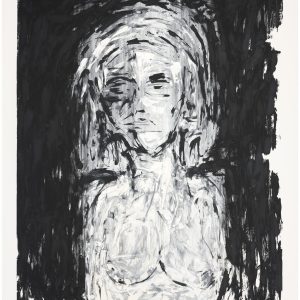

In 1955, at the age of 19, Hunt witnessed the open-casket funeral of Emmett Till – a young African American from Chicago whose brutal, racially-charged murder became an enduring symbol of the civil rights movement. Marking a critical turning point in Hunt’s artistic journey, he created two works in direct response to the event: Prometheus (1956), where Till’s suffering is linked to the mythic narrative of the god of fire, who endured eternal condemnation at the hand of Zeus, and Hero’s Head (1956), immortalising the image of Till’s disfigured head through welded steel. Through the allegorical narratives of mythology – of indiscriminate punishment and metamorphic transformation – Hunt found a way to reconcile the darker realities of contemporary America. In his later career, Hunt reflected, ‘My own use of winged forms in the early ’50s is based on mythological themes, like Icarus and Winged Victory. It’s about, on one hand trying to achieve victory or freedom internally. It’s also about investigating ideas of personal and collective freedom. My use of forms has roots and resonances in the African-American experience and is also a universal symbol.’[2]

Hunt’s lifelong interest in mythology finds further expression in Linear Peregrination (1962), an expansive, open-form steelwork belonging to the artist’s ‘Metamorphosis’ series. Inscribing space through a meandering trinity of points, the sculpture’s chromed armature assumes the abstracted shape of a bovine, drawing dual inspiration from Picasso’s 1942 found-object sculpture, Bull’s Head, while referencing the Greek myth of Europa and the Bull. Representing the largest ‘drawing in space’ created by Hunt in the 1960s, Linear Peregrination’s winding metal odyssey probes space in ways unattainable with other materials, subverting traditional sculptural modalities to expose its exterior parameters and voided spaces as an analogous interface.

Created in the same year, Organic Construction, Number 1 (1962) continues Hunt’s explorations with linear-spatial configuration, shaping a protracted, lateral form that extends through space, favouring horizontal expansion over vertical height. ‘I like the idea of creating this extension rather than having to grow up from the base more vertically’, Hunt noted. The sculpture’s central and sole point of vertical progression converges on two thick horns that create the composition’s balance. Demonstrating Hunt’s proclivity for disassembling and reassembling parts of old works, the horns are inherited from the artist’s earlier 1959 sculpture Longhorn – created in San Antonio, Texas. The work was dismantled, and its parts reused and grafted to cultivate new, hybrid shapes, which became some of Hunt’s most notable sculptures. Elicited through the titular word ‘construction’, Organic Construction suggests a material and discursive life in constant evolution – fully realised yet maintaining an openness to further growth.

In the mid-1960s, Hunt began to explore more homogenised, enclosed forms, moving away from the calligraphic style of the linear-spatial sculptures. Produced within this transitional period, Opposed Forms (1965) embodies composite conditions, in which rounded, organic shapes cohere with constellations of axial geometry. A chrome-patinated bodily mass rests upon three attenuated legs of wrought steel, evoking a life form that appears almost otherworldly. Synthesising volumetric density and the delicacy of sculptural drawing in space, Opposed Forms tethers Hunt’s varying stylistic influences – from elements of the machine-made, to forms inspired by Surrealism, science fiction and biomorphic growth.

‘These major works by Hunt, welded while still in his 20s, call to mind the influence of Pablo Picasso, Julio González and David Smith. This body of work confirms Hunt’s dazzling talent at an early age and manifests his undeniable importance as an American sculptor. Not since his 1971 MoMA retrospective have so many of Hunt’s masterworks been on display in New York.’

Jon Ott, Biographer of Richard Hunt and Chairman Emeritus of the International Sculpture Center

Exploring the possibilities of diverse metals, including copper and aluminium, as observed in Coil (1965) and Tube Form (1966), as well as techniques of casting, showcased in Serpentine (1969) – one of the first works the artist cast in America – Hunt’s progression into the 1970s laid the foundations for his later large-scale public installations. From his formative student years at the SAIC to the monumental, commissioned works exhibited in institutions across the United States, Hunt’s protean experimentations in scale, material, composition and subject matter collectively form the epic odyssey of an inimitable sculptor.

Richard Hunt, Early Masterworks, 13th March – 13th April 2024, White Cube New York

About the artist

Richard Hunt was born in 1935 in Chicago, Illinois, where he continues to live and work. He has exhibited extensively, including recent solo exhibitions at KANEKO, Omaha, Nebraska (2022); Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California (2022); The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois (2020–21); Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens (2018); Koehnline Museum of Art, Oakton College, Illinois (2018); The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2016); Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Illinois (2014–15); Galesburg Civic Art Center, Galesburg, Illinois (2013); Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso, Indiana (2012); Peninsula Fine Arts Center, Newport News, Virginia (2011); and David Findlay Jr Gallery, New York (2011).

Hunt’s work is held in over 100 public collections including Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio; Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, California; MFA Houston, Texas; MoMA, New York; National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among others.

The artist is the recipient of numerous awards, among which are the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship (1962–63); the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center (2009); the Fifth Star Award from the City of Chicago (2014); and the Legends and Legacy Award from the Art Institute of Chicago (2022).