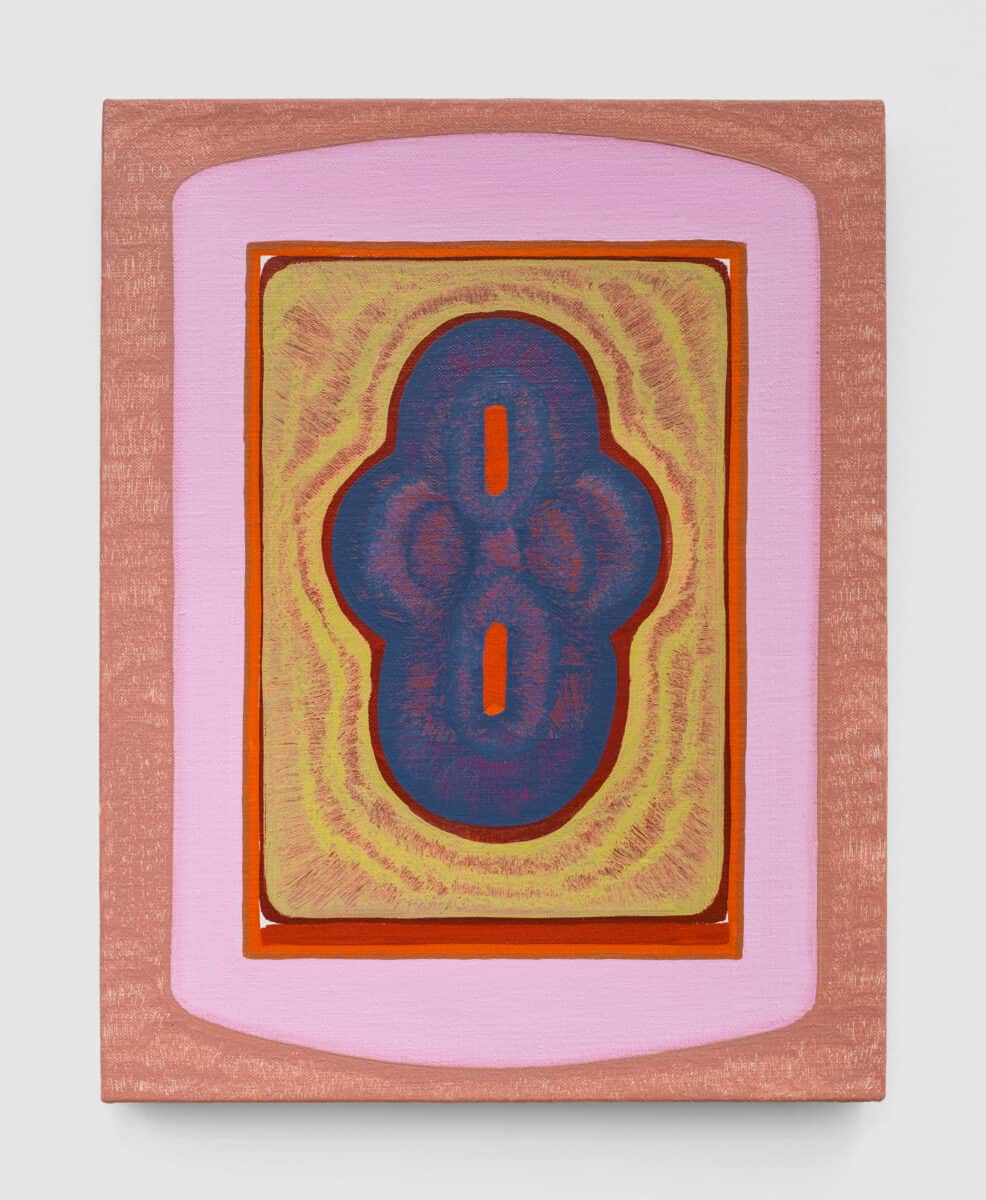

It takes more than a quick glance to comprehend Lily Stockman’s deceptively complex paintings. Artworks that are remarkably difficult to write about, perhaps because they are formed of a language entirely of their own. Her recent exhibition, The Waves at MASSIMODECARLO marks the gallery’s first solo presentation of the California-based artist’s work. The pieces on show beguile the viewer with rich and sumptuous colour combinations – crackling orange, red earth, Holbein brown, and Fra Angelico blue – in undulating and biomorphic, yet distinctly boundaried forms.

The exhibition births a cyclic dialogue between the space itself and the works on show; resisting the ‘white cube’, MASSIMODECARLO’s London home is a 1723 Georgian townhouse, its architectural grammar – cornices, dentils and decorative elements – are subtly echoed in the paintings. The Tyger pieces are displayed on the reverse of a wall adorned with rococo revival mirrors and are painted to reflect their ornate form. This is just one of the clever and somewhat hidden secrets within Lily Stockman’s work, a practice predicated on the need for lengthy consideration by the contemplative viewer.

Her sources of inspiration are markedly multifarious. For Stockman, nature is a central generative force, with memories of a bucolic childhood spent in New Jersey amongst apple orchards and hay fields underpinning the artist’s continued reference to the experience of being within a certain landscape.

Simultaneously, the body of work on show at MASSIMODECARLO is inspired by Virginia Woolf’s experimental 1931 novel with which it shares its title. Reading like a painterly stream of consciousness, the text is narrated in soliloquy by six friends from childhood through old age. It relies on the fallibility of memory and is a continuously slippery read, drawing the viewer’s focus to the delicate use of language and vivid descriptions instead of a unifying plot or overarching message.

This, in my mind, is the central connection between the work of fiction and the exhibition – a refracted, undulating and inconsistent story that insists upon consideration of minute detail. One can be sucked into connecting a certain painting with the landscape from which it was drawn. For instance, a well-informed viewer with horticultural passions might take the time to find the connection between the small orange, mauve, and umber painting Meadow Brown and the larger work Great Dixter (Meadow Brown mimics the wings of the butterfly of the same name, its form is repeated within Great Dixter, named after the beloved garden in the Kent countryside that is home to the very same butterfly). To me, this is the true gift of Stockman’s paintings – the fact that there is always more to her work than meets the eye, and the

invitation offered to the viewer to uncover these hidden mysteries.

The exhibition title ‘The Waves’ is drawn from Virginia Woolf’s experimental 1931 novel of the same name, a kind of stream of consciousness narrated in a soliloquy by six friends from childhood through old age. What drew you to this text? In what ways has it influenced the series?

The Waves is written in soliloquy and reads almost like a play. The standard structure of a novel –“Cecilpicked the apple”– is instead a present-tense embodiment of a character’s consciousness– “I am picking the golden apple from the black bough.” I only read The Waves for the first time this year, it’s was one of Woolf’s novels I could never really get into. I had abandoned it years earlier. But now, maybe it’s just getting older, I find it electrifying and moving because it’s a shape-shifting novel, it’s time travel, it’s abstraction. You, the reader, can inhabit an experience you’ve never had, through the eyes of someone with whom you might have nothing in common. This is the way I hope to make paintings.

The exhibition reflects on your own memories of youth, as well as the collective memories of yourself and your siblings. What was the process of excavating these experiences like? In what ways are the works imbued with these recollections? In particular, your relationship with nature as a child.

I have three sisters and we are extremely codependent and intertwined in each other’s lives. We have no memory of grownups from childhood, we were out playing in the fields and woods, building forts, creating entire systems of hierarchy with battles and kidnappings and treasures. No TV, no influence of popular culture. Chickens, horses, sheep. We rode to school in middle school on several occasions. We had no full-length mirrors in the house and we were not permitted to discuss our appearances. Work ethic and academic and athletic excellence was the value of the household. I laugh now because we are all a tiny bit vain and love trashy TV as adults, but we are all deeply absorbed by my parent’s values, but in different ways.

I feel like your work toys elegantly with the relationship between the written word, poetry, language and painting. You reference the ‘grammar’ of your paintings and refer to small works as ‘verbs’ and large works as ‘nouns’. What is this interface between different forms of communication in your practice? Why the correlation between spoken/written language and painting as a lexicon?

Because there’s no language to talk about abstract painting besides comparison to other senses. “It makes me feel XYZ.” I’m interested in the structure, the flying buttresses that hold up a poem, for the same reason I’m interested in the way Rita Ackerman rarely paints off the edges of her canvases; she is aware of the edge, she is painting in the middle, she has her own invested rules of structure, and that gives the paintings their language.

You describe the show as mediating on ‘the experience of being in the natural world’ – rather than based on the passive observation of landscapes, it’s really about the embodied experience of being immersed in an environment. Is there a particular work in the show that feels very true to this reading for you? How so?

The big blue painting, Bell Buoy. I have wanted to make a painting about approaching the island in the fog and navigating around the perilous rocks by the tolling of the bell buoy. The sound delineates an invisible landscape, and it’s also a guide. In thick fog I am essentially blind, and yet I can still navigate through the ocean by the sound of this bell, which tolls faster and more furiously the worse the weather and wilder the waves.

Talk a little about the places that have influenced this particular series of works.

I grew up in a pocket of green farmland in central New Jersey. It is very beautiful, it’s a great secret. Most people don’t think of rolling bucolic farmland when they think of New Jersey. We grew up on a hay farm and had a derelict apple orchard. Childhood time was marked by bow season when you had to be careful in the woods so you wouldn’t get shot with an arrow, pruning season when there were men in trees and the sound of rackety branches falling, pheasant mating season when we’d hear the double beeping of the birds in the fields, apple season, hay season. Winter was spent playing ice hockey.

I went to school around New England and I think the Shaker influence was enormous. Economy of means, whistle while you work, if you’re going to add an object to the world make it useful and beautiful. I moved to Joshua Tree when I was 22, and have lived out there in the Mojave Desert off and on all these years, with stints in New York and Jaipur. I’ve lived in Los Angeles for ten years. I visit Maine in the summer to see family. It’s a tiny island with a one-room schoolhouse and you get there by mail boat. Fishermen and artists.

Speaking of place, in some ways this exhibition is very site-specific, responding to the architecture of the 1723 Georgian townhouse within which it is displayed – MASSIMODECARLO’s London home. The Tyger paintings in particular seem to playfully recall the rococo revival frames of the mirrors positioned on the other side of the wall. Do you see this as a site-specific show? What is the impetus to respond directly to a certain exhibition environment within your work?

Yes very much so. It’s a thrill to make work in collaboration with a vernacular architecture, which becomes the personality of the show. What a joy to make work for a space with a point of view. What could be more boring than a white cube. Like, it could be anywhere in the world, who cares, blah. Give me crown moulding or give me death.

Your lifelong pursuit of abstraction was informed by two specific and quite unusual apprenticeships – Buddhist thangka painting at the Union of Mongolian Artists in Ulaanbaatar, and later, traditional Mughal miniature painting in Jaipur. Can you briefly describe the influence of these experiences on your work?

In Ulaanbaatar, I learned how to make circles and in Jaipur, I learned how to make straight lines.

Lastly, I am interested in your process and the role of dichotomy – you seem to toy with the boundaries between rigidity and fluidity, smoothness and texture and the pre-mediated versus the instantaneous. How do these contractions inform your practice?

Maybe that’s just what it’s like to be a woman.

View this post on Instagram