iPhones have pretty good cameras. More than just rendering a subject in high-resolution, they can endow a sense of affective mythos upon it; readying it to be stored in our individual pocket archives. For his installation-based exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms, Mahmoud Khaled embraces the possibilities of these digital records to explore poetic alternatives to antiquated history-telling. Titled Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, this immersive exhibition draws upon Max Klinger’s 1879 series of etchings titled Fantasies on a Found Glove, Dedicated to the Lady Who Lost It, as its methodological springboard. Working from an imagined anecdote about finding a lost phone in a public toilet, Khaled plays with a soft form of critical fabulation (to borrow Saidiya Hartman’s term) to narrate the life of the phone’s mystery owner – Mr O for short. In turn, questioning the rigidity of archival technologies that so often overlook, or outright refuse to tell, the histories of folks marginalised or who live queer.

Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, extends Khaled’s recent work around ‘house museums’ – described by Dina Ramadan in a recent Art-Agenda conversation with Khaled as, “space[s] dedicated to the legacy of the person (real or invented) who lived there.” Rather than a museological-type display of rows upon rows of fetishised objects endowed with value through their auratic proximity to Mr O, as common practice in house museums, the personal fragments – the photos, the screen-shots, the notes and other memorabilia – saved upon this lost/found phone set a general ambience for Khaled’s installations. Across the exhibition’s three rooms, we move from fresh encounter to eerie squeal; not coming to know Mr O, the person, through some regurgitative action of biography, but rather, we becomes attuned to how a narrativizing of a life can move our bodies to feel the “very erotic, elegant,” but “troubled” personality of another.

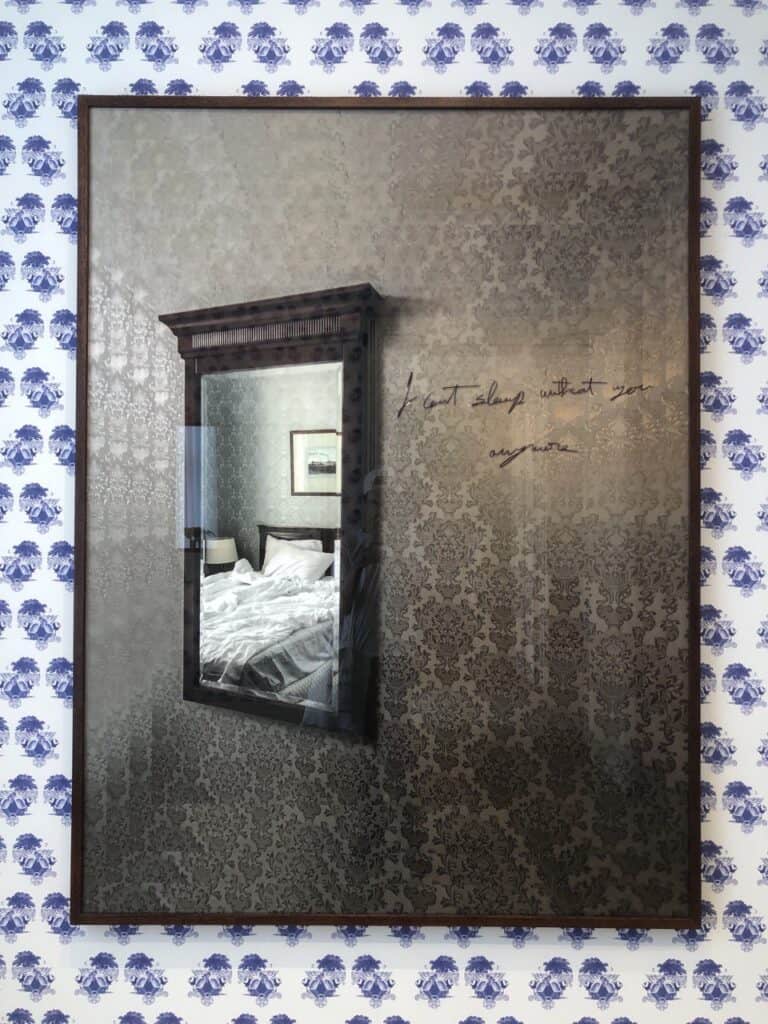

“I can’t sleep without you / anymore”, the opening line to a love letter, a memoir, a novel? Written here, in sharp freehand script, the poetic sentence acts as an epigraph to Khaled’s exhibition; one that is not only intimately bare but lays bare the tensions at the heart of Khaled’s fantastical storyline: a narrative where desire and anxiety rub, where dream and reality pour, together, out from the archive. Framed within a frame, next to another frame within a frame, this delirious note adorns a large photograph of a bedroom wall. With its olive green flock wallpaper and deep mahogany mirror, at first glance, the face of this pictured wall provides us with an inkling into Mr O’s aesthetic tastes – the man likes classical forms and baroque flourishes. There is something more to this photo, however, something disquieting. Formally, within the photograph’s composition, the wallpaper contorts as if we were looking at this plain wall through some sort of kaleidoscope, whilst the iconographic details refracted in the mahogany mirror – where we see a simple photograph or print of dark chimneys leaking delicate trails of smoke into a baby blue sky above a limpy bedspread – give the scene a dissociative air. In this way, Khaled’s photo feels more like an apparition than a realistic appearance; a restive dream rather than some regurgitative document.

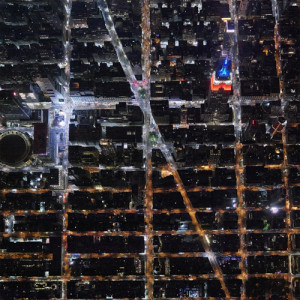

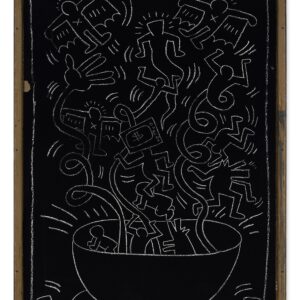

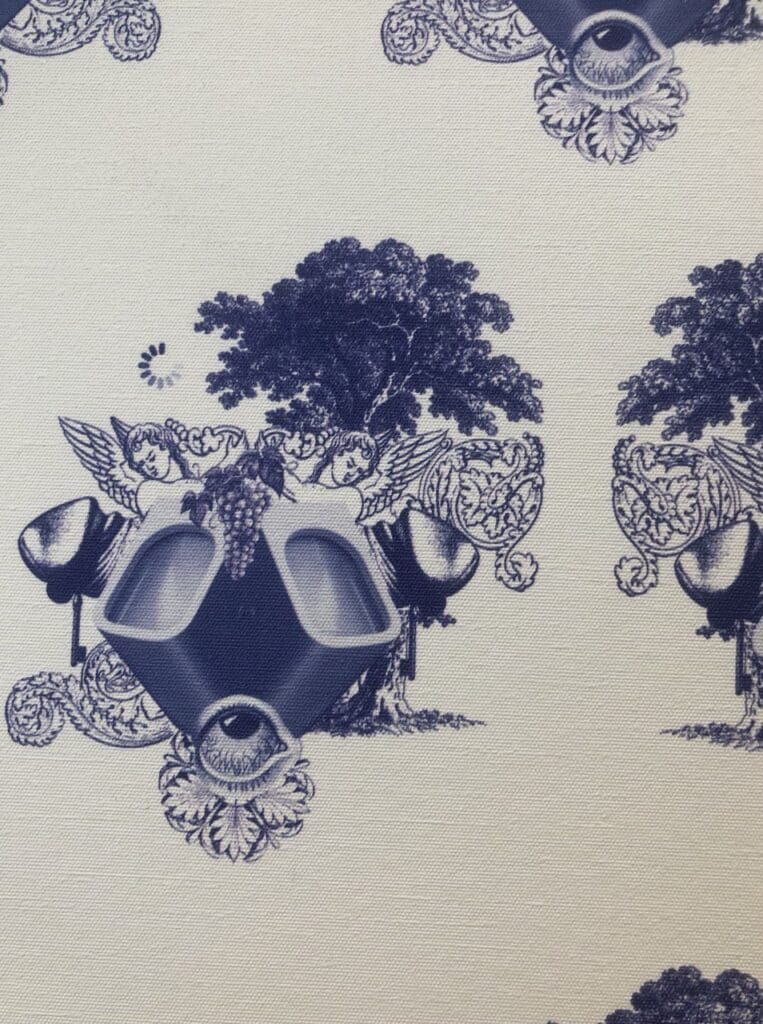

Khaled appears to lavish liturgical investment in each of the details of his installation. Within this first room, Khaled’s unnerving photograph is hung upon a flock wallpaper of his own design. Much like that opening poetic scrawl, the wallpaper’s motif alludes to a narrative. In this case, the mythology behind the exhibition: Khaled finds Mr O’s lost phone in a public toilet, delighting in this, he eyes the phone’s content and constructs, through this fortuitous archive, a domestic portrait of Mr O. Simply a blue print upon a white ground, the repetitive motif tells this myth through an iconic collage: cherubs, penis tips, urinals, and a veined eyeball all sit alongside baroque frills, a classical tree, grapes, and an iPhone buffering sign. Brought together, as if on a rudimentary phone photo editor, this absurd composition is both humorous and touching. Perhaps the epitome of delightful; encharming.

The second room of Khaled’s house museum brings us closer to the troubled life of Mr O’s. Entitled Calm, this immersive sculptural environment haunts through its paradoxical pairing of an app soundscape and exaggerated furniture. This sense of unsettledness is provoked through Khaled’s attentive use of material: rippling suede curtains (I say suede as the fabric has a thicker more fleshy tactility than velvet) line the perimeter of the gallery space enclosing an evocatively phallic daybed that has been upholstered in black leather and finished with S&M style belts. Juxtaposed with these items of semi-anthropomorphic furniture, the mellow voice of a Siri-esque app narrator speaks past me, filling the gallery space with a taster of their daily sleep podcast. Mixing white noise and oceanic waves, the slow enunciation of this disembodied voice is wholly seductive. Tuning into this alluring cadence, the promise of better sleep achieved by listening to their daily podcast is held out to us, we just need to sign up for the monthly membership.

If Calm is a space where we witness Mr O’s unsettledness, then, in the lower ground floor of Khaled’s exhibition, we see the protagonist’s unrequited aspirations. Composed of a soft grey carpet, a circular bed, and ambient melodies, For Those Who Can Not Sleep takes up Khaled’s evocative use of furniture as a cipher for sexual desire; in particular a super-masculine fantasy drempt through the clash of 60s decorum and baroque excess. Echoing the phallic daybed of Calm, the circular bed at the heart of this installation is upholstered in black leather with its mattress being pinned in place by a singular S&M belt running its diameter. Referring to Hugh Hefner’s iconic bedroom office, Khaled’s bed slowly rotates with quiet screams – the awkward sound of 60s mechanics. These (un)sexual noises fade in and out of the installation’s soundscape; a tranquil meander between ascending violins and the ding-ding-ding-ding tiptoeing of piano keys. Despite being intoxicated by this beautiful eulogy to those aspiring to descend into the erotic depths of the midnight mind, I cannot help but remember the apparitional disquiet of Khaled’s bedroom wall photograph. “I can’t sleep without you / anymore.” If that image preluded a narrative about anxiety, desire, dreams, and reality, then this work makes the tensions innate to Mr O’s life wholly apparent – felt.

By clashing suggestive forms and sly atmospherics, Khaled not only alludes to Mr O’s psychological troubles but pointedly references the spurious promises innate to sleep-aid and dating apps; technological dependencies that Mr O – here a monika for a collective we – cling to in the hope of easing his mental strife: his anxiety, his loneliness. By bringing us disquietly close to Mr O, Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it leaves one feeling like a voyeur, or awkward witness, tiptoeing through an ultra-fine space of affective possibilities; a critical space where affect allows one to practice history-telling critically and otherwise.