MAXXI returns to join forces with Bvlgari to present the third edition of the MAXXI BVLGARI Prize, a project supporting and promoting young artists. Together, they showcase, in the upper galleries of the museum, the site-specific works by the artists Alessandra Ferrini (Florence, Italy, b. 1984), Silvia Rosi (Scandiano, Italy b. 1992) e Namsal Siedlecki (Greenfield, USA, b. 1986). The 2022 winner will be announced in the fall.

Giulia Ferracci curated the show, opening today in the scenic Galleria 5 of the Roman museum. This brings together three works conceived, produced, and created exclusively for the Prize. The winner will be chosen by an international jury composed of Hou Hanru, Artistic Director of the MAXXI, Bartolomeo Pietromarchi, Director of MAXXI Arte, Hoor Al Qasimi, President and Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, Chiara Parisi, Director of the Pompidou-Metz, and Dirk Snauwaert, Director of WIELS Contemporary Art Centre. The winner’s work will finally enter the MAXXI’s permanent collection.

As Giovanna Melandri, President of Fondazione MAXXI points out, the show addresses some urgent questions of our days.

“The relationship with personal and collective memory, with history, with nature, are themes that have become increasingly central in the light of the profound geopolitical, social and ecological transformations we are witnessing, and the MAXXI BVLGARI Prize could only reflect this. The Prize, which represents one of the most important appointments for the Museum – developed together with Bulgari, our strategic partner since 2018, a company that has always been attentive to research and with which we share the mission of investing in the creativity of our time – puts us behind the gaze of young artists, giving us a glimpse of the future and perhaps the best way to deal with it. Welcome to the finalists! It is a pleasure to have you at MAXXI”.

While belonging to our collective history, these geopolitical questions somehow fail to surface in the quotidian life of everyday people. The exhibition addresses, for example, the colonial past of Italy, among other nations, and the complex relationship between humans and technology. These questions, as they are investigated by the three finalists, have deep roots in our past, but their influence still impacts profoundly our present.

The exhibition opens with Gaddafi in Rome: Notes for a Film, by Alessandra Ferrini, a video installation analysing Muammar Gaddafi’s first official visit to Italy in 2009. This happened during the signing of the Treaty of Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation between Italy and Libya. While this helped Italy to secure fuel supplies and ease the flow of migrants to the southern coasts, it remains a highly controversial moment in European history. It meant negotiating with a dictator, bringing back the policy of refoulement, as well as causing human rights violations.

The videos put together a meticulous reportage on Gaddafi’s official visit to Rome, one that caused a frenzy in Italian media. Especially La Repubblica began a real-time reportage of the event of unprecedented scale. The videos bring forward the relationship between the speed of communication and the effective understanding of complex geopolitical events, the media spectacularisation of events and Italy’s complex relationship with its colonial past. Yet, Gaddafi in Rome does not offer clear-cut solutions, leaving the viewer to draw their own conclusions.

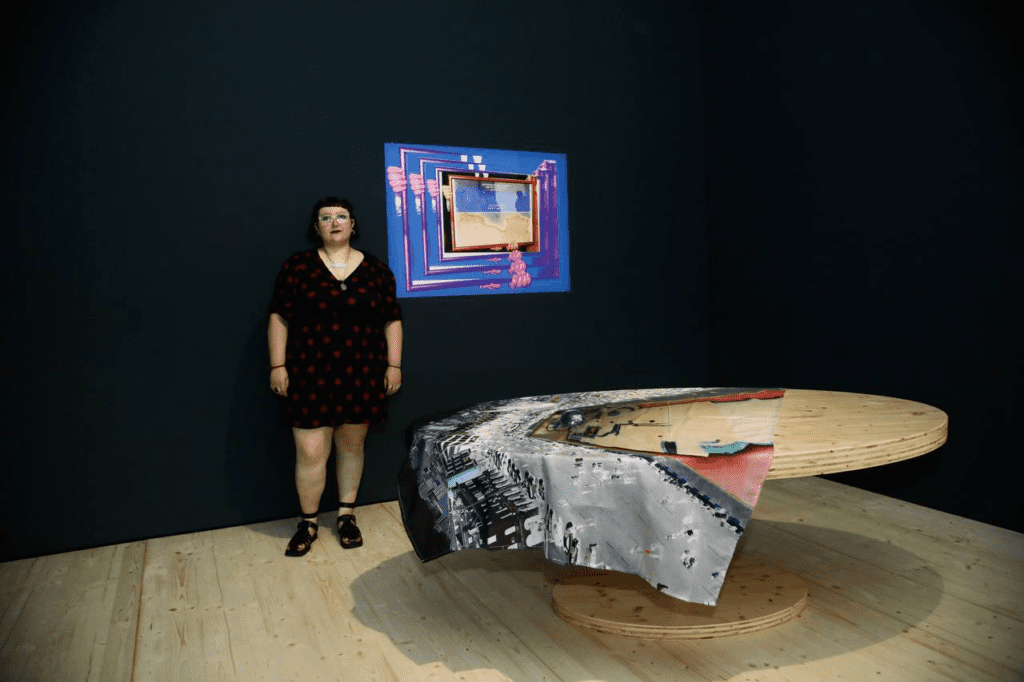

Namsal Siedlecki focuses on another hot topic of our present: Nature, and the relationship between humans and new technologies. His work, Nuovo Vuoto, talks about absence, about the artist’s need for empty spaces. Yet, it does so through a thorough exploration of the physical world, of matter. Siedlecki starts from the inside of a bronze hand purchased online and goes on to find the “original sculpture” that contained it. With 3D scansions, vector reconstructions, and robotic technologies, the artist displays six works. These all come in different materials, consisting of a sculpture and its plinths. The viewer moves through the different stages of mutation of our existence, of matter, of technology and of our relation to it.

Silvia Rosi‘s Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense (2022) concludes the exhibition with a reflection on memory, both collective and individual. Investigating her family history and identity heritage, Rosi dedicates her work to the Ewe and Minà languages, once spoken in Ghana and Togo. Despite the French and German-speaking colonialists’ attempt to eradicate it, the Ewe language survived thanks to local families, linguistic studies and craft practices whereby you decorate fabrics with phrases in Ewe. Rosi’s work, presenting three groups of photographs and videos, highlights the role of language in the affirmation of identity, especially within the history of colonisation.

THE FINALISTS

Alessandra Ferrini (Florence, Italy, 1984) lives and works in London. An artist, researcher, Italian educator based in London, her work is developed through the use and combination of different expressive languages, from moving image to installation and performance. Ferrini’s research is rooted in the study of post-colonialism, historiography, archival processes and critically analyses the relationships between Italy, the Mediterranean region and the African continent.

Silvia Rosi (Scandiano, Italy, 1992) lives and works between London and Modena. Rosi is a Togolese-Italian visual artist, whose work focuses on the theme of origins and the personal, historical and social characteristics that determine an individual’s identity. Through the genre of self-portraiture, she recaptures her family’s experience by updating stories, memories and ancient traditions. Inspired by her Togolese heritage, her works privilege the photographic medium and the moving image combined with textual fragments.

Namsal Siedlecki (Greenfield, USA, 1986) lives and works in Seggiano (GR). Siedlecki places the constant transformation of matter, both natural and artificial, at the centre of his work, enhancing its infinite expressive and semantic qualities. Stories of rites, memories and ancient traditions inspire the particular technique and aesthetics of his works, sculptures and installations in which the process of manipulation, control and change of materials evokes the ancestral question of the relationship between man and nature.