Photographe : Luc Castel Crédit photographique : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Luc Castel

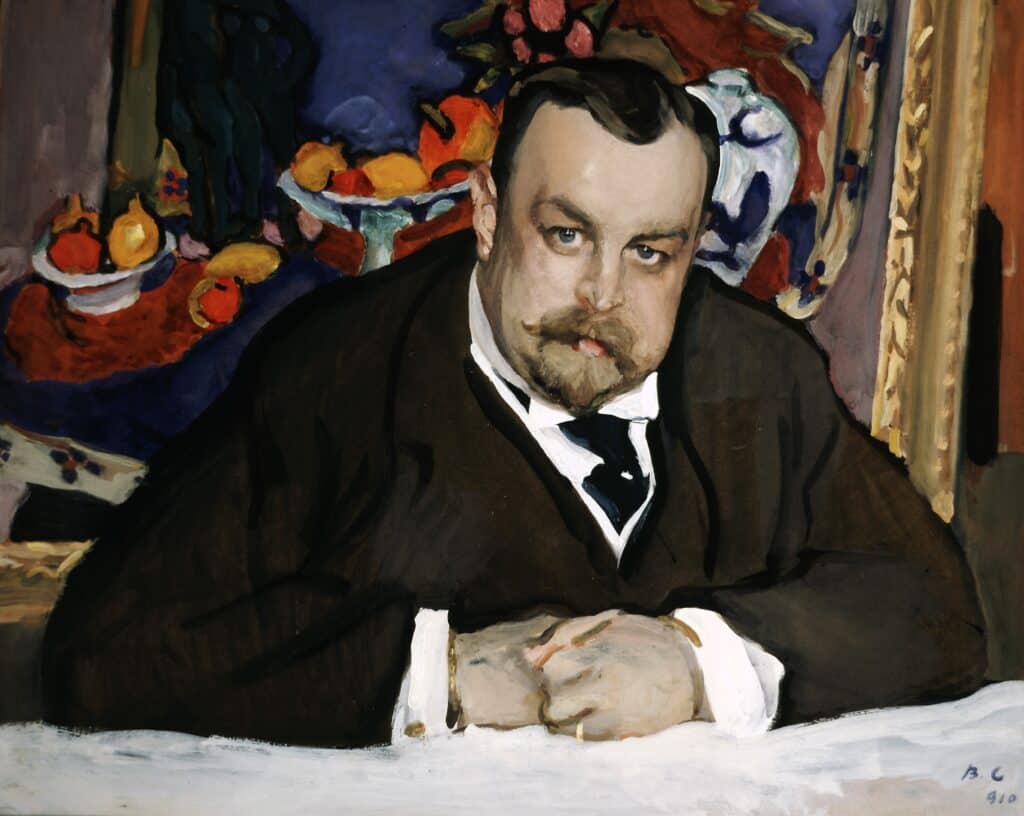

Anne Baldassari is the General Curator of The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art exhibition, showing from 22nd September at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. The show pays tribute to the two renowned Russian art collectors and brothers, Mikhail and Ivan Morozov, whose early adoption of many works of impressionism and post-impressionism from 19th century France fostered a collection of some of Europe’s most iconic artworks and visual spectacles. Romantic, tragic and intensely moving, the show follows the development of the brother’s collection over time, through its idealised theosophy-inspired artistic impact on a Russian audience, to the untimely suppression of its catalogue under the USSR’s regime.

What do the works in this exhibition proffer for art in your view; the impressionist philosophy, how do you see it?

Throughout the rooms, it appears that the Morozov brothers wanted to recreate the first impressionist exhibition in 1874, pursuing the same subject matter as this show, the same images by Pissarro or Sisley or Monet. Their inclusion is a way to create a kind of habitat – ‘this is earth’, ‘this is tree’, ‘this is sky’, ‘this is water’, and it’s a way to look at the natural elements, not through the gaze of academic painting, metaphor etc. but as an object of fact. It’s not just a question of optic and retinal perception, but to recreate a concept through the direct description, it’s very simple. There’s a reason it was so provocative at that time, because the public, the contemporary society, was unable to look at a ‘tree as a tree’ or ‘grass as grass’ – only through the chain of signifiers, so they lost something very important. The same is true of the Russian landscape tradition, and so the Morozov’s followed the impressionist paintings in particular to find a new story, through feelings, dramaturgy, social dramaturgy about landscapes, to be able to look at the natural environment in a new way. So, the revolution, the same impressionism that was impactful in the French academic scene, was strong and provocative too for the Russian interpretation of the world.

So, it’s simple; grass is grass. But it’s a good way to start in the construction of painting as a new language, as far that painting is a language and we have to learn it, to speak it, the impressionists engaged with the simple parts of its structure, fact by fact. For a modern audience, the experience of this language is also interesting, maybe it could play this role for the French public now, providing a path to see the natural world in another way. Today we are in a moment of natural alienation, to return to an old concept from the renaissance, but as our painting, cinema and literature change our understanding of nature, maybe it’s useful again to say that ‘earth is earth’, ‘tree is tree’, and to re-evaluate.

I think that’s definitely true, because it’s such a digitised world at the moment, and we have this excess of culture, so maybe bringing it back to life is very interesting.

Yes! To speak about the internet etc., painting is so lost today, so this dynamic of looking at pictures, and images first before going to the painting is very important. Because we must remember that a painting is a fact, an object preceding the images of it. It’s not an image. We need to look at a house online before going to purchase it in person, but to look at a painting the same way? I’m not so sure. The de-vitalisation, de-naturalisation produced by the internet is very dangerous, because again we are losing something very important.

The ecological aspect should also be looked at, particularly the second room in the exhibition, to see all the paintings in the Morozov mansion on the eve of catastrophe. This is also where we are, just before the tsunami so to speak; we are feeling the cataclysm, and we feel it strongly. I wrote the show’s text during the confinement, and I was in the same spirit in this respect. We share a context with the collection in this way.

There’s a consistent focus on outsiders and strangeness in the works gathered here, particularly with Gauguin’s works, that was quite new to the contemporary audience the Morozov’s entertained. This conflict with their own culture must have been quite revolutionary, how do you think that they related to this?

I’m delighted that you’ve asked this question, nobody else has. It is absolutely true, with both of the Morozov brothers, there is this interest in ‘the other’. It was an interest that probably came from and was fulfilled by their contact with other cultures, which follows from how they ran their industry. They grew cotton in South America, had it weaved in England, and then sold their products in Asia. From this multicultural capitalism, an economic and financial logic is mirrored in their interest in the arts ranging from the Middle East, to Africa, to Polynesia. It also alienated them from Russia itself. Mikhail thought Russia to be barbaric at the time, full of voracious people, and so that it was important to create a change here and to become more like Europe. To bring a new European feeling, or way of feeling.

In that way is it an idealistic collection, bringing this European Romance to a land which was perceived to not have it?

I think that there are two aspects to it, two levels. First, this sort of pragmatic opening up to the world, and bringing the appearance of greater civilisation and education. Then, on the second level there is a very strong personal line that runs through the works that focuses on romanticised light, the world of antiquity in the sun, nudity, the Latin cultures. Again, specifically in Gauguin, or in Bonnard’s triptych ‘The Mediterranean’, this was the world that the Morozov’s wanted to have, whilst living in Russia, in the snow and mud.

Though Mikhail started the collection he was not a Romantic, but when he passed and his financier sibling Ivan took over, these themes become more apparent. You can see in the works the sensation that one is about to lose nature, about to lose this classical past. There is delectation of the scenery, intellectual contemplation, but also this mourning feeling that permeates the space. Even in the largest rooms of the exhibition, there is something very sad about the paintings’ atmosphere. It is a kind of mausoleum to the lost paradise which they never possessed.

In that respect, if we start with Mikhail who isn’t very Romantic despite his interest in art, and move to Ivan who takes things further towards this feeling, as the curator today, what is the role that you’re bringing to this story? Would you consider yourself a Romantic in that regard?

I am certainly a Romantic, and I suspect that you are too. This is a singular collection, with two distinct characters in Mikhail and Ivan, and so I want to give it its place, a position as it should be; to give their dramas they lived and ideological pressures they experienced justice. This is the way in which I have tried to do the exhibition, and effectively it is Romantic, but through this service. That being said, there is a particular narrative that runs throughout. Alongside the works, we can see the Morozov’s personal story develop dialectically, and emotionally, from the portraiture in the first rooms all the way to the chapel arrangement in ‘The Story of Psyche’ at the end. What is interesting about this structure is its reflection of the quest for culture and beauty found both in Ivan Morozov’s pursuit of art and the story of Psyche and Eros featured in the final room. A quest for knowledge and transcendence, through the belief of Theosophy, that moves towards encountering truth through beauty.

Through this belief, both brothers were also sponsors of the composer Scriabin, who also followed this philosophy. Just like how the Morozov’s pursuits of art were stifled under communism, this musician’s final work was never completed – an ambitious plan to host a one-hundred-day long concert in a giant glass sphere – and for a while we toyed with doing this here at Louis Vuitton alongside the art collection. However, this did not come to pass.