$69.3 million is a lot of money to spend on something you cannot touch, that does not occupy space and that cannot even be seen without flicking a switch. Now the dust has settled on Beeple’s epic auction debut, it is time to soberly consider whether it is worth it. Spoiler – it probably is! We are, after all, living in the future.

March 11, 2021 was the first time that Christie’s sold a purely digital artwork, but in order to begin to get to grips with this seemingly outrageous turn of events, we need to look at the term ‘NFT’, which you’d be forgiven for never having heard before now. An NFT, a non-fungible token, has a unique value and represents a unique digital file or line of data, and the only way to understand that is to divest yourself of the urge to compare it to other tangible things. A fungible asset is something that can be exchanged for something else of equal value and it can be interchanged precisely because it can be divided into units. A £10 note can be swapped for ten £1 coins; a gold bar can be exchanged for two half gold bars, or equal weight of liquid gold or equal weight of gold earrings; a bag of saffron can be equally divided into five smaller bags of saffron. All these are fungible assets, but this should not be confused with liquidity, which just means that a thing can be exchanged for money or other goods wherein the value (the price) is contingent on other facts. A non-fungible token, then, is something that can only be exchanged for one unique thing, a file or recording, for example, and has no value outside that. So, the NFT bought at Christie’s can only be exchanged for Beeple’s Everydays – The First 5,000 Days; the token is unique, like a key that unlocks the file, and there can be copies of the file, but the NFT is the ‘original’. It is absolutely counterintuitive and mind-bending.

A painting is a liquid asset, which is ontologically and economically different in every meaningful way from a non-fungible token, so it will not help to think of the Beeple NFT, when considering either value or quality, in terms comparable to a painting sold at auction. It’s just too different. Indeed, artworks are usually liquid assets and rarely – though possibly – fungible, so the arrival of the NFT in digital art as an item of monetary value is new and shocking but we have to keep in mind that an NFT is a different thing from all the things we are used to in art, so we cannot judge it like a painting. To be sure, consider that we have no difficulty comprehending that paintings are liquid and not fungible assets; we intuitively know that if we split a bag of oats in half we have two bags of oats of equal value, but if we cut the Mona Lisa in half we do not have two new units of equal value that add up to the value of the undivided painting. In order to understand the Beeple story, then, we need to add the concept of non-fungible tokens to our artworld discourse.

Enter Beeple, or Mike Winkelmann, graphic designer by trade, artist by graphic design. In 2007, Winkelmann made an image of his uncle Jay, affectionally called Uber Jay, and posted it online. Then, the next day, he made another, different image. And then the next day and the next… He called them his Everydays because he made one every day, and every day he posted them online. It took 13 years to amass 5000 images and here we should pause to think about just how much time has passed. 5000 images is a lot by any standard; 13 years, just more than a decade, is not a long time, but it is long enough for every one of us to have aged and for our lives to have changed (psychologists say a person’s opinions, beliefs, worldviews and personalities organically regenerate every ten years so what you think or feel now is unlikely to be what it was a decade ago).

However, 13 years is an ice age in tech: Beeple began his project a month before the first iPhone, when Twitter was just a year old, when Facebook was only just a toddler, which was a time before Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok. The earliest of the Everydays pre-date the social media frenzy that has engulfed the lives of so many. We are talking here about a generation of young people who have no concept of what it is like to not own a smartphone and who have no concept of fame and scandal as it is traditionally generated by the tabloid press. Imagine – even if these kids know who Princess Diana and Michael Jackson are, they possess no working, experiential concept of the power of the press to peruse, built up and tear down, which they now witness – and aid and abet – on social media.

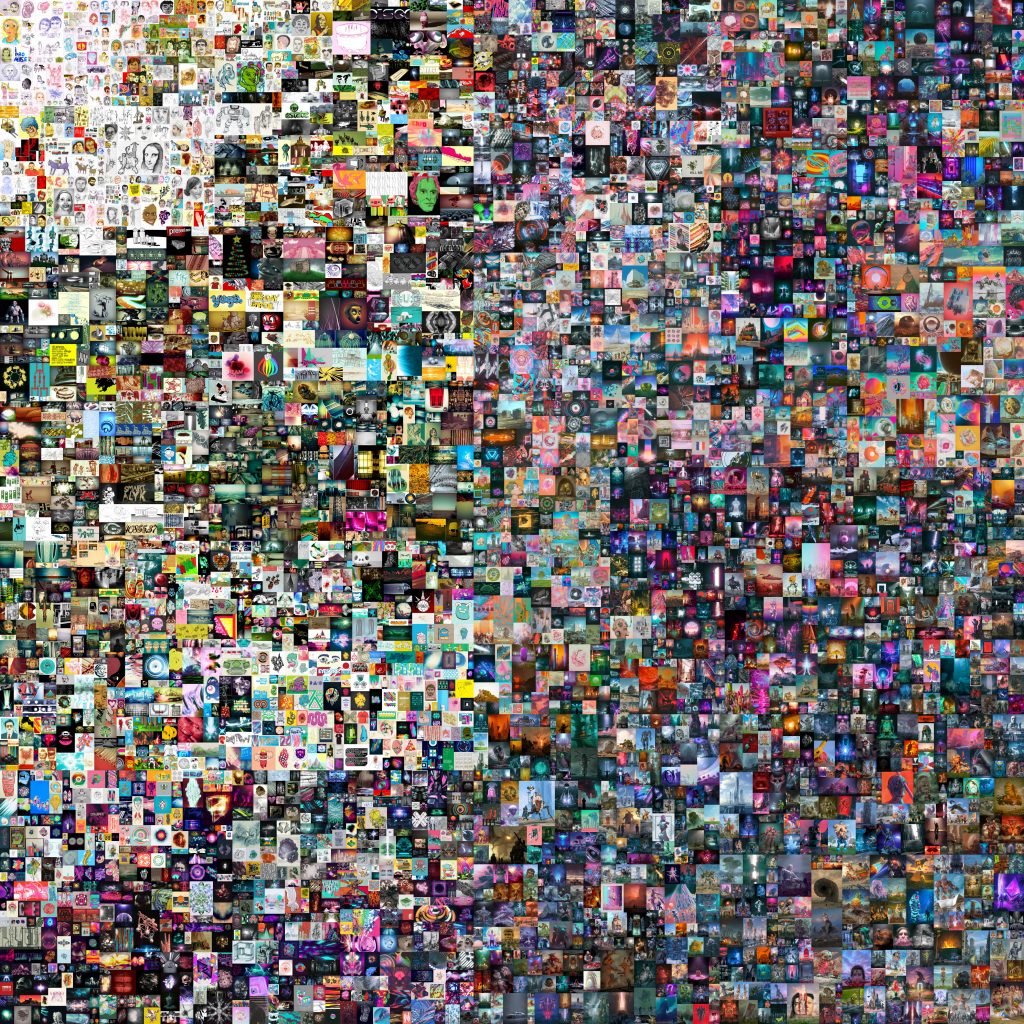

There is, then, something both achingly contemporary and refreshingly historical in Beeple’s Everydays – The First 5,000 Days. Broadly speaking, Beeple’s style is somewhere between pop art and comic book; some days he does cartoonish portraits, others he does sci-fi-looking apocalyptic landscapes; sometimes it’s an icon of consumerism, such as McDonald’s or Ocean Spray Cranberry (a la Warhol), and sometimes it is a juxtaposition of objects, like a building in the sea or a crystal in the woods; and some days it is a seemingly abstract pattern with a vaguely concealed order or image. When you make a new one every day you have licence for some of them to be below par, but a lot of them are great because Winkelmann’s graphic designer’s eye for colour, shade, line and shape is second to none; forget what they are supposedly about, they are aesthetically successful nearly every time. Then, when you stitch 5000 of them together you have a beguiling mosaic of images that approaches the sublime.

In short, Everydays – The First 5,000 Days is a really decent artwork, and certainly one of the very best examples of digital art in a field crammed with juvenile rubbish spouted by grown adults with little sense of artistry. Whether it is worth $69.3 million is another matter that requires we think soberly about two uncomfortable truths. First, we need to confront the fact that nothing is really worth anything. Money is just a construct, a very important one, but nonetheless, it is basically fictional – the buyer never had sixty-nine million, three hundred-thousand-dollar notes, nor did the bank have the cash in its vaults – it is just lines of numbers representing the possibility of a transaction. And the things you buy – you want them, you need them, but what are they really? It’s just stuff. Stuff that will either perish soon enough or outlive us.

Think about property: your tiny one-bed flat in Zone 3 is not worth £500,000, but having somewhere safe and warm to live is priceless; a Toni & Guy haircut is not worth £60 when a competent barber could do it for a fraction of that, but the feeling you get when it’s done, having been treated like royalty, is worth it. Money buys stuff and the only thing that matters is how we feel about that stuff because none of that stuff lasts forever and none of that stuff is worth, in and of itself, the price we pay or, frankly, anything at all. It all goes to dust in the end. It just ends up another spiralling flicker in the cosmos, so really nothing matters as much as how we feel in the here and now and if we feel good about our financial transactions, then so be it.

Second, given that we all die in the end, there is no meaningful difference in the value to us of goods and services, tangible and intangible things. Sure, it seems insane to pay anything much at all for a digital image, an encrypted file, but not more insane than having to pay upwards of half a million pounds for a fairly substandard house in London. Think about the price of food: the idea that we should pay anything over cost-price for food – stuff we need in order to survive, which gets used up in seconds and then squelched into nutrients and waste, only to have to start all over again in a matter of hours – is an absolute scandal. The greatest and most insidious wickedness of capitalism is the idea that a few individuals can profit from feeding – and starving – the rest of humanity. Again, the only real measure of worth here is whether the buyer feels satisfied with their NFT.

The thing with commodities is that it is just a question of who will go first – us or the things we own – so we should be impressed that so many things do outlive generations. The really interesting debate that Beeple gives rise to, even given that nothing truly lasts for ever, is about how long it can possibly last. It is through a confluence of good fortune and ingenuity that humanity embodied its creativity in paintings, sculptures and books, for example, which all seem to endure for a long time. Just reflect for a moment on the fact that ancient Greek statues are still around, all those Leonardos are 600 years old and a printed book, which is literally just bits of paper, can survive in good condition for 150 years.

Although the NTF can last forever, since it is just a conceptual token, the artwork it represents could have a limited life: technology is usurped and becomes defunct by itself all the time, so there may be a time in the not-too-distant future when we do not use jpegs anymore and then, later, when we hardly have the devices to open and view them. If this sounds unbelievable, think about the VHS, cassette tape, Betamax, floppy disc, and even CDs, MP3s, even vinal and 35mm film… Sure, they may not vanish completely, at least not in the next century, but formats become obsolete as technology moves on and they became harder to track down and to access. There is no reason to think the jpeg won’t go the way of the VHS sooner rather than later and, at that point, the buyer of Beeple’s NFT might have cause for sober reflection. Hopefully, in the event, they will reflect that nothing lasts for ever and they cannot take anything with them anyway, so they will enjoy the feeling it gave them, however fleetingly.