“It was the biggest and best show we have ever done to date,” said Joseph Bannan, (CEO of Woodbury House Art in London,) in reference to their latest project. Woodbury House, (a private art studio in Soho, London) worked with Startnet and Saatchi Gallery, to present Nightlife—Works by Richard Hambleton and Franc Palaia.

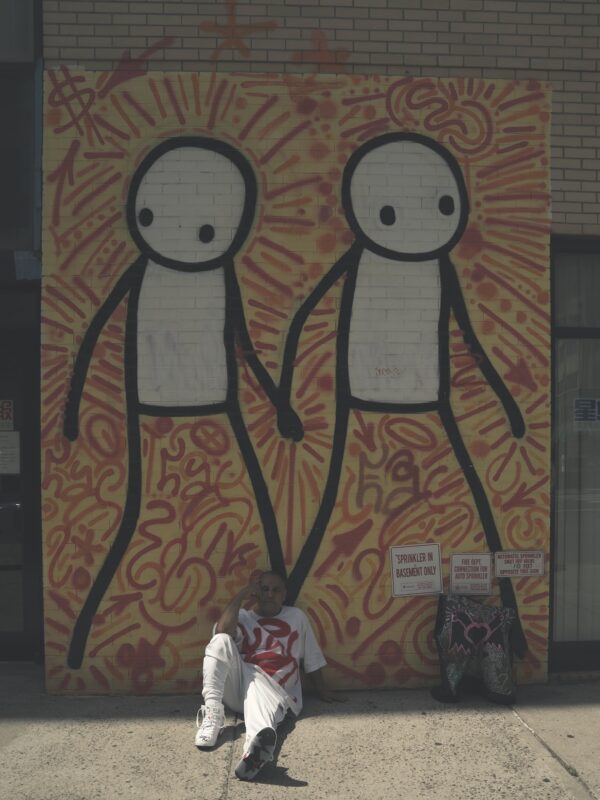

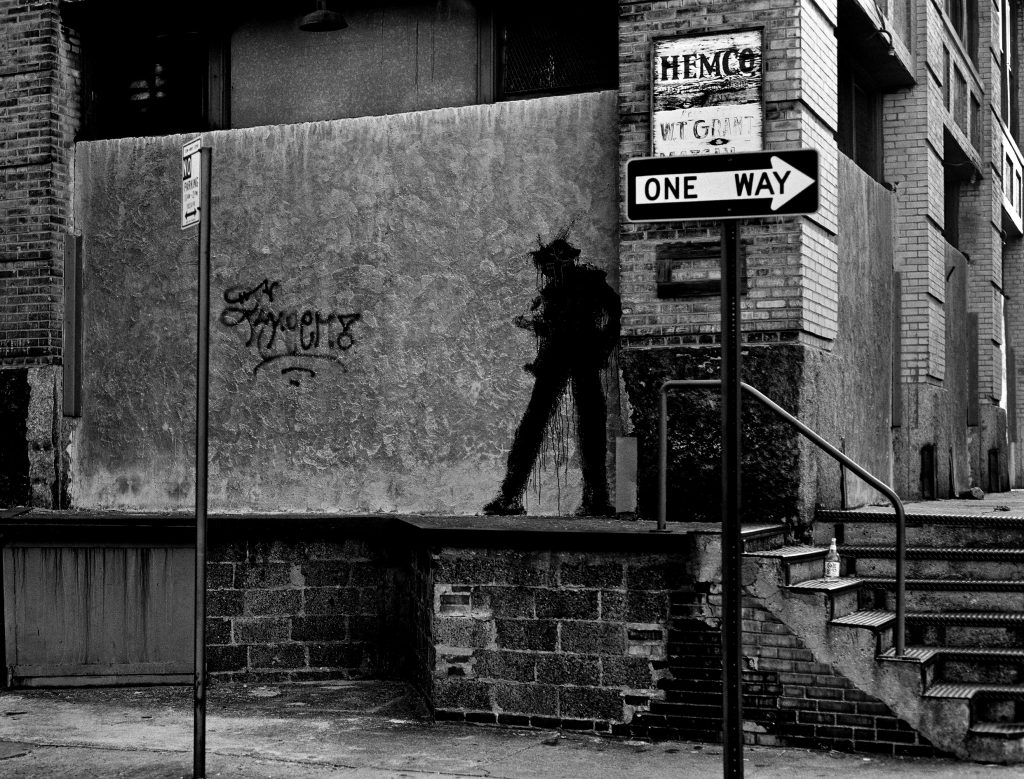

The show revealed twenty-two original works by Canadian/ American street artist Richard Hambleton, (30″ x 84″ acrylic on Japanese Kinwashi paper,) in conjunction with American photographer Franc Palaia’s images of Hambleton’s original “Shadowman” street art series. The series was done in the mid 1980’s, the peak of Hambleton’s career. Each one is signed, and numbered in an edition of 53 (22/53, 1985.) At this point, Hambleton’s reputation as a controversial, but frustratingly brilliant, conceptual artist was gaining momentum. Meanwhile, his strange, enigmatic charisma, was appealing, and even seductive. He was by no means, loved and worshipped by all, but he did have a loyal clan of contemporaries, followers and friends, including Jean Michel– Basquiat and Keith Haring to name a couple.

On from 21st through 25th October, 2020, the exhibition ran in tandem with the third anniversary of Hambleton’s passing, 29th, October, 2017. A number of mysterious years elapsed in between Hambleton’s heyday and his death. The artist self- isolated, withdrew, and eventually, disconnected from New York’s contemporary art scene altogether. It only took a few short years after Hambleton’s death, however, for the contemporary art world to notice and even foster, a newfound, or rediscovered, interest in the artist.

The Canadian born conceptual artist, often referred to as the “Godfather of Street Art,” outgrew his provincial origins and relocated permanently, to New York’s City’s Lower East Side in 1979. Here, Hambleton would join the various underground, counterculture, creative movements of the 1980’s. From the inception of his career, the artist was consumed by a need to paint reality. Much of “reality” at the time, though, was anything but picture perfect. Senseless violence, crime, and murder threatened the city’s streets. Instead of shying away from the darkness that plagued the city, though, Hambleton used his work to seize it.

Hambleton’s violent depictions of murder scenes (large, and looming dark figures covered in bright red paint,) and his “Shadowman” paintings appeared on abandoned buildings, in empty alleyways, on street-corners, and in any other communal space that the artist deemed worthy. New York became the artist’s canvas, upon which he brought the foreboding darkness that beset the city, to life.

“There was this strange, eerie mood. You were always looking over your shoulder, whether someone was actually following you or not. It was ominous, and Richard really captured this”

said fellow artist and former friend of Hambleton

Hambleton pioneered the concept of “Public Art” and many refer to him as a, (if not the,) founder of the genre. As a nod to the artist’s influence on this particular art form, Bannan and his team decided not to hang Hambleton’s works on the walls. Instead, the exhibition would simulate a work of public art. The captivating (30″ X 84″) works stood side by side, carving up the remaining negative space for viewers to engage with. Visitors walked around, or to the side of, each piece, replicating an interaction between a passerby and a piece of street art. The design made a “significant impact,” and, according to Bannan, reflected “the way Richard would have wanted it.” This was crucial; Because Hambleton had such a unique, and beautifully perplexing artistic existence, the need to do his story justice was paramount. Woodbury House had a responsibility to curate not only a successful show, but one that would also move and teach its’ audience. In my opinion, the studio succeeded.

By the mid-eighties, Hambleton was a household name and his work was more sought after than that of his contemporaries. Penny Arcade (a brilliant artist in her own right) “spent so much time with Richard. I would go to sit and watch him paint for hours.” Their immediate connection grew especially strong because “we were both conceptualists.” “Fundamentally,” she said, “Richard and I shared a serious devotion to the purity of our work.” Presumably, this made Hambleton’s self-sabotage all the more difficult and painful to watch. Penny stressed, though, that Hambleton was not the usual, or “typical” sort of self-destructive person.

“Richard was different. He seemed to get a sick pleasure out of destroying any potentially good thing in his life.”

Clearly, Hambleton had his demons. What began as occasional, recreational drug use (which was unfortunately common amongst creative clans of the time), quickly became routine. It is nearly impossible to tell Hambleton’s story without acknowledging his absolutely overwhelming and all-consuming addiction. The drugs, without a doubt, fueled Hambleton’s creativity, while simultaneously providing a psychological comfort, or warmth even, which numbed him. Only then, was Hambleton able to handle the manic and dismal mAll Postsess that his life had become. His addiction was a divergence from facing realities, and as these realities worsened, so did his compulsion. Ironically, Hambleton was fixated on representing reality through his art, but when it came to his life, he was using and every façade he could. People in Hambleton’s circle, however, were not blind to their friends’ problem. Some tried to help but were unsuccessful, and many others had already given up. They watched as Richard’s addiction forced him into an even deeper hauntingly dark and lonely life. He self-isolated and withdrew.

“He would disappear, just like that, for weeks on end… no one knew where he was.”

said Penny Arcade.

With one bender after another, countless cancelled shows, apartment evictions, and ultimately a cancer diagnosis, Hambleton’s life tragically spiralled from one disaster to another. Perhaps it was my imagination, but Penny’s patience seemed to wear thin,

“He brought struggle and misfortune on himself. Richard wasn’t… you know… a Basquiat type, who we can all agree was a victim of his circumstance. Richard wasn’t oblivious to what was happening to him—he was driving it!”

Penny Arcade

After a while, even Hambleton’s closest friends, confidantes, partners, and lovers struggled to keep up with his drug fueled, erratic ways. “Richard was a real character. He lived just right on the very edge of his life,” said a former friend. Hambleton’s body worked tirelessly to fight off disease and addiction with little avail—his own face was barely being held together by bandages and gauze. Despite the horror he was enduring, or perhaps because of it, Hambleton’s mind and soul needed to be put to work too. So, he turned inward, deeply inward, toward whatever was left of his artistic ability, his talent, and his creativity.

Hambleton did not, and would not, stop painting; He remained obsessively devoted to the conceptualist within, and for as long as possible he kept his work, and the intentions behind it, pristine. “Richard was devoted, and held on to, for as long as he could, this incredible purity which fueled the creation of his work” explained Penny Arcade. For the majority of his life, Hambleton balanced the starkly different identities his single body contained. An artist, for example, who will only put his best, most original work on view versus the junkie who would sell anything to get high. Somehow, he kept each and all of these fragments in check, and met their needs.

Richard Hambleton’s story, even when told through the eyes of his former friend and confidante is “one of… the most grotesque” (as far as the history of art goes,) but also the most astonishing. “In the face” of this dark and dirty, “subhuman trajectory that he went on, was this extraordinary purity of intention,” said Penny Arcade. At the bitter end, though, something changed. Perhaps for one second Hambleton was distracted or just grew too weak to keep the opposing fragments of himself in balance. The self-destructive and desperate addict was gaining strength. A split second, though, was all it took for the dark side of Hambleton’s psyche to shift the balance in its favour. “I couldn’t believe Richard’s work in those last few months of his life. I was shocked he would even show the paintings in public, let alone sell them” said Penny Arcade. A menacing desperation, which Hambleton had tirelessly fought off, caught up to him. Deep physical and mental suffering overwhelmed Hambleton, and a throbbing need took over. “In the very end…” said Penny Arcade “the junkie in him won out.”