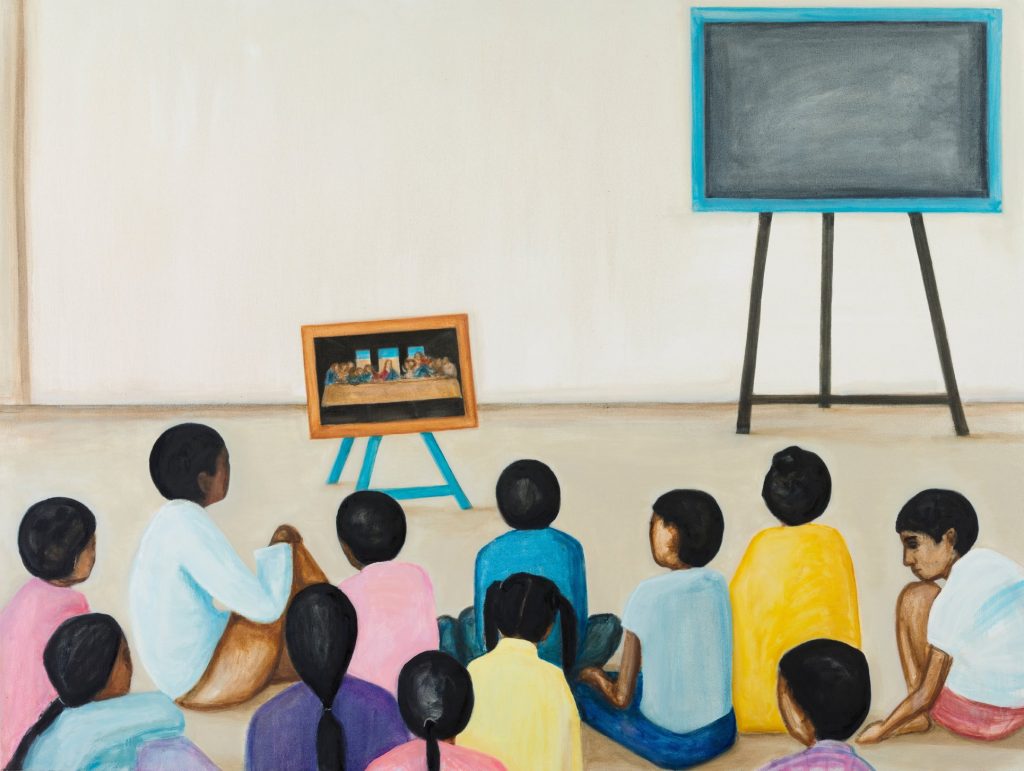

Matthew Krishanu Mission School, 2017,

Twelve children sit on the floor of a classroom, cross-legged or knees bent up towards their chins. They are brown-skinned with black hair. The painting, called ‘Mission School’ (2017), is by Matthew Krishanu. The imagined viewer of this work is positioned just behind the group of children, looking over their heads towards what they are looking at – a painting propped on a low easel. To the right of the easel as the children look at it is a blank blackboard. On closer inspection, the painting on the easel is Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’, presumably a copy. ‘Mission School’ is made up of distinct sections.

Take away the children, the blackboard and the painting on the easel and it would be an abstract painting made of two colour fields separated by a horizontal zip. There is a distinct fatness to most of the surface. The children occupy the very bottom of the picture plane, and the lack of pictorial depth reinforces their proximity to the imagined position of the viewer. Flatness and a lack of pictorial depth give way only in one part – the reproduction of ‘The Last Supper’. Christ is at the centre of the work, the viewer’s gaze directed by the diagonal of his left arm. This is a sudden appearance of the conventional perspective associated with Renaissance and pre-modern canonical art history, puncturing the rest of the picture plane. The children looking at this painting within a painting, this moment of interruption, look bored.

Matthew Krishanu, Everyday Heroes

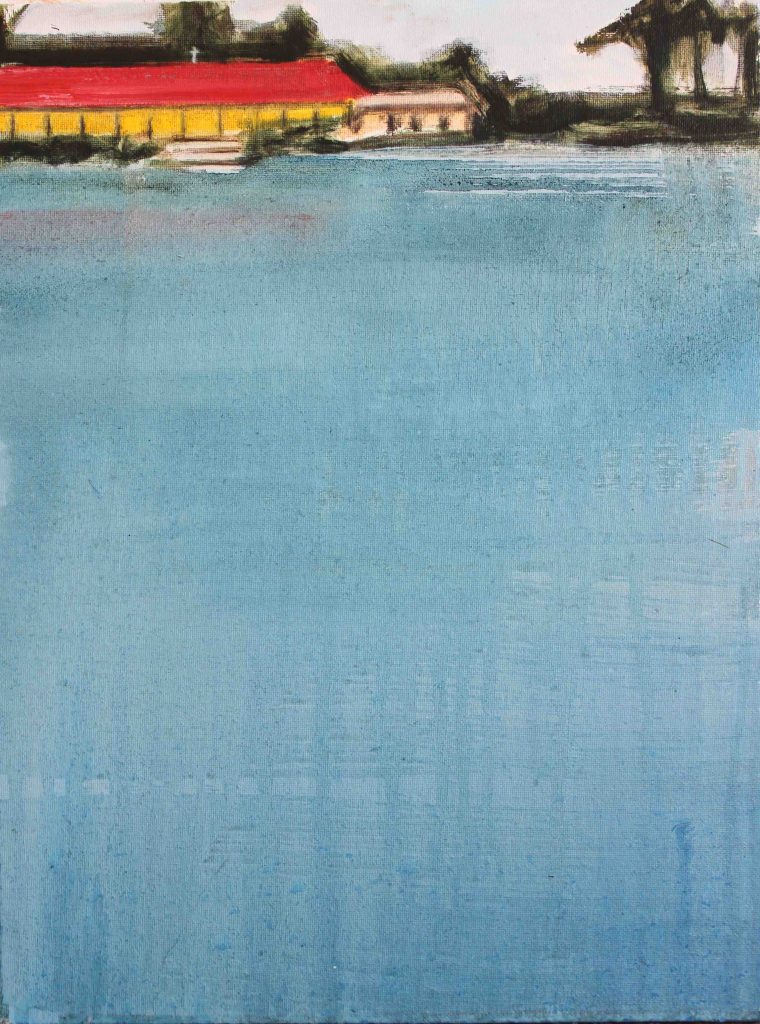

Krishanu’s use of pictorial depth (or fatness) and shifts in registers between different parts of the surface of paintings results in subtle ambiguities and dissonances. In the House of God series,

Krishanu paints together areas of fattened space, rendered in layers of one particular colour, with half-remembered figures and places that are pushed towards the edges of the painting. The surface of

works such as ‘Church, Tree and Field’ (2020), and ‘Church Tower and Field’ (2019) are predominantly taken up by a large painted area of colour that might plausibly be read as a field (with reference to the respective titles of each work). But it is also possible to read these areas as a field in a different sense; a colour field, the term that writers sometimes used to describe abstract painting in the USA in the 1950s and 1960s. These ‘fields’ have a pictorial depth that is largely fattened so that area becomes almost wholly abstract. The ‘subject matter’ of this series, the churches, towers and crosses, is very literally at the margins. The ground beneath each church of these two paintings forms a thin, hard edge, below which subject matter dissolves.

Matthew Krishanu_Mission House and Lake, 2020,

Christianity is a minority religion in South Asia, largely a legacy or a leftover (depending on your point of view) from European colonialism. As theorists such as Homi Bhabha have written, the Bible and the rituals of the Church were used to ‘civilise’ the colonised, but that mission was always undermined by the local nuances, misreadings and mistranslations that happened in the transmission of the Bible. For him these mistranslations undermined the authority of the civilising mission creating instead ambiguity and subversion: “the colonial presence is always ambivalent, split between its appearance as original and authoritative and its articulation as repetition and difference” (H.Bhabha ‘The Location of Culture’, Routledge, 1994, p.107). The religious figures and buildings in Krishanu’s works might be understood as embodying the half-remembered traditions of a long-gone power, slowly disappearing into the land, into the fields of colour that surround them. The figures in ‘Procession of Priests’ (2020) seem to gain collective meaning from each figure’s similar devout pose, but individually these figures and buildings are unmoored, always just surviving on edges or thrust out towards the viewer at the bottom of the picture plane. Depth, context, anchoring of figures within a background is only sporadically present. It is there contained within the reproduction of that mainstay of the western canon, ‘The Last Supper’. It is also there, albeit in a different way, in Krishanu’s paintings that feature two boys which he has indicated are him and his older brother. For example in ‘Mountain Tent (Two Boys)’ (2020), the tent is physically anchored to the landscape through the tent poles, and the boys seem secured to the land through their positioning that is less towards the edge of the work. There is even a tenuous sense of foreground and background around them, grounding them perhaps.

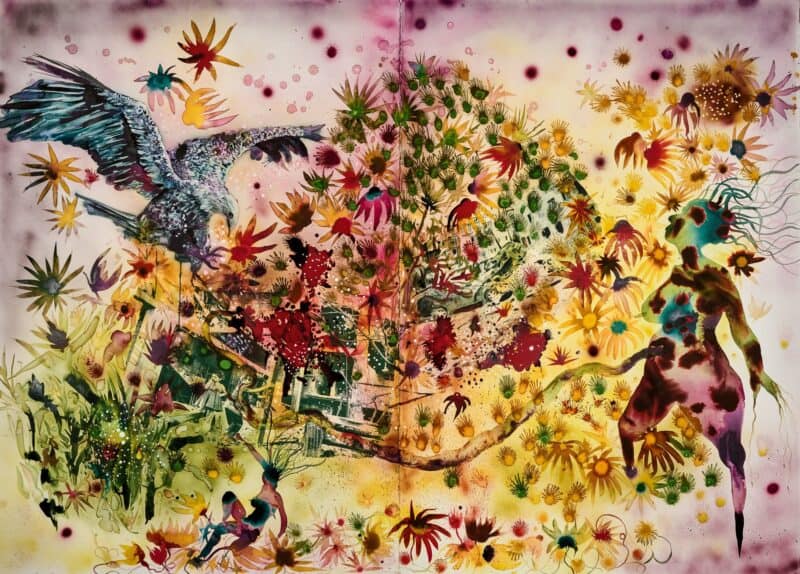

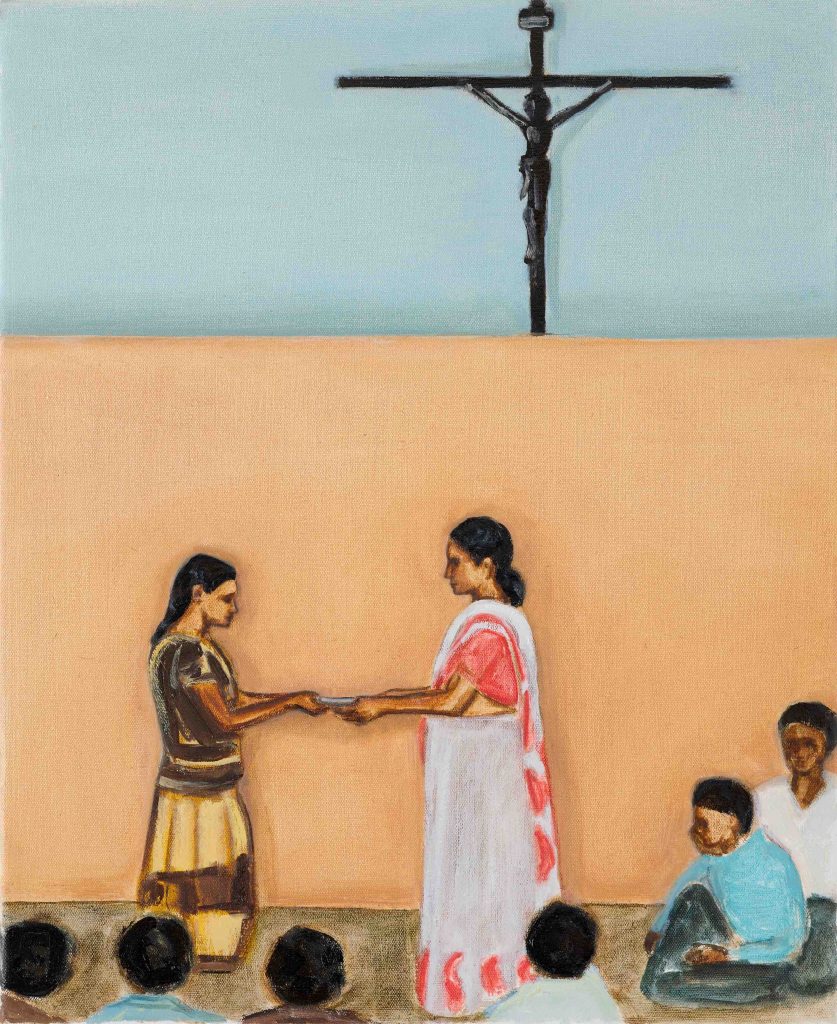

Matthew Krishanu_Ceremony, 2018_

The children in ‘Mission School’ sullenly look at the reproduction of the Western canon presented to

them. The blank blackboard suggests they don’t seem to have much to learn from it, or perhaps it is

more that they know that the history and the subject positions that painting assumes (Christ at its centre, the viewer’s gaze always directed) are not for them. Their space is at the edges of this foreign,

imperial narrative, an afterthought to the great civilising mission. They are observers rather than participants, but they are also observing the decline of that mission.

They might only be allowed marginal and precarious subject positions but there is a tenuous security in those positions, watching as imposed traditions slowly sink into the unforgiving land, serenaded by the crows.

Matthew Krishanu ‘Picture Plane’ Niru Ratnam 16th September to 24th October 2020 niruratnam.com

About the Artist

Matthew Krishanu (b.1980) was born in Bradford and is based in London. He completed an MA in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins in 2009. Recent solo or two person exhibitions include: New Figurations, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai (2019); House of Crows, Matt’s Gallery, London (2019); The Sun Never Sets, MAC, Birmingham (2019) and Huddersfield Art Gallery, Huddersfield (2018); A Murder of Crows, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (2019).

Recent group exhibitions include Everyday Heroes, Hayward Gallery / Southbank Centre, London (2020), A Rich Tapestry, Ikon and Lahore Biennial, Lahore (2020); Childhood Now, Compton Verney, Warwickshire (2019), The John Moores Painting Prize 2018, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool (2018); In the City, East Gallery, Norwich (2018); Contemporary Masters from Britain, Yantai Art Museum, Jiangsu Art Museum, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, China (2017-2018). He has works in collections including the Arts Council Collection, the Government Art Collection, Huddersfield Art Gallery, the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, India and Jiangsu Art Museum, China.