On March 21, Art in the Age of Anxiety did not open as planned. Culminating a decade of research, the landmark group exhibition at Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates explores the manners and behaviours of a world reconfigured by digital technologies. The exhibition was always intended as a confrontation, an experience of bombardment to conjure the information, misinformation, emotion, deception and secrecy that structure contemporary life. These are principles curator Omar Kholeif observes in our “post-digital” condition; they are also elements that exacerbate our anxious experience of the Coronavirus pandemic, the alarming reality that prevented the exhibition from opening.

Kholeif is prolific. As a writer, curator and cultural historian he has led over 100 exhibitions, special projects and commissions globally, he has also authored and edited two dozen books and catalogues on contemporary art. Named as one of Apollo Magazine’s 40 under 40, he has held positions with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Whitechapel Gallery, Cornerhouse and HOME, Manchester, and FACT Liverpool. Today, he is Director of Collections and Senior Curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, a boundary-pushing institution that has defined the cultural landscape of the Arab Gulf, and, particularly through its Biennial, shaped seminal dialogues with artists and cultural thinkers from South Asia, the Arab world, and Africa.

Whether engaging with the politics of art in the Arab world or post-internet cultures, Kholeif’s books and exhibitions expose the latent structures of fast-paced social and economic change and hyper-mediated technological evolution. Though his pace of thought, work, writing, production is impressively relentless, as for everyone, the new reality of the pandemic has imposed pause, cancellation, postponement.

Art in the Age of Anxiety is subject to this deferral, its themes exacerbated by the enforced closure. If we could visit the exhibition, we would find ourselves in a labyrinth of tilting walls and shadows, conceived by Kholeif and architect Todd Reisz to conceal and reveal 60 works by more than 30 artists. In dormancy, those structures remained.

As lockdowns have quieted the velocity of frantic lives, we have found ourselves in a more static relation to the panic and anxiety prompted by our digital context; in stillness confrontation and inspection. So too the ideas of this unseen exhibition are cast more starkly, more definitely, by this strange quiescence.

The third of a loose ‘trilogy’ of exhibitions charting the shifts in context and consciousness shaped by digital and internet technologies, it follows the genealogical survey Electronic Superhighway (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016) and the more intimate reflections of I Was Raised on the Internet (MCA Chicago, 2018). FAD spoke to Omar over Zoom, from London to Sharjah, in late April.

Find part II of the conversation here.

The exhibition is open to the public from June 26 – September 26 2020, at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE.

Antoine Catala, Don’t Worry (Rock) (2017) and Everything is Okay (Ground) (2017). Installation View: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic.

A note on context: This conversation took place in late-April, in the middle of lockdowns that had given a sense of extreme pause to life as it was being lived. In the past fortnight, though the pandemic still rages, global events have shifted us rapidly out of this experience of “hiatus”. As newsfeeds and news cycles mutate, they imply a shifting consciousness, at the level of content, if not behaviour. The following conversation touches on the possibilities of pause in the context of technology and the lockdown; cautious optimism might ask if current events will connect with experiences of the pandemic to resist a return to the “status quo”.

FAD Just before we connected today, I saw a video of your opening remarks as you convened the 2019 March Meeting. In it, you were talking about obsessions: it’s clear that the subject of this exhibition is one that has haunted you for a very long time.

Omar Kholeif I always tell people that my obsession with the Internet began when I was an early teen, living in Saudi, and my dad brought home our first computer. Schooled in a British American system, I encountered art, but never artists with names like mine. When I asked the teachers why they told me there were none. So, this slow dial-up connection became the only way to try and piece together what was hidden from me.

I am often asked: “Why are you interested in these two disparate subjects – art from the Arab world and technology?” For me, they’re not disparate; they’re intertwined – they’re both about hidden voices and their representation. And that’s really all I care about – what’s beneath the surface, how I can make it visible.

FAD My exploration of this exhibition has been fragmented and remote, through cloud-based folders of images with ambiguous file names, each sparking loose and associative google searches, attempts to accumulate information on the artworks themselves. It felt like glimpsing a thought process, the structure of an idea, unmediated by a viewing experience.

Omar Kholeif So, that sense of not being able to capture a glimpse, being unable to weave a thread through the context of the exhibition, is something we tried to create within the viewing experience, even formally.

As a curator, you’re often considered the conduit that helps the artists express their voice. But I see my role as a storyteller. I’m a writer first and foremost, I write fiction and I write poetry, that’s what I love. I actually went into curating because I knew it would be a field where I could write, reflect and think. Then came the joy of experiencing art and building exhibitions. And this is the most ambitious exhibition that I’ve ever done in terms of build. I had the privilege of working with the architect Todd Reisz, who is an old collaborator and friend. Previously, Todd worked at OMA with Rem Koolhaas, he was a professor at Yale School of Architecture for several years, he has spent time in the UAE. I find most architects tend to place the architecture before the art, but Todd is very sensitive to the art and the ideas themselves.

When we started to talk, we explored Dr Caligari and Labyrinth, questioned what being shot down a fibre optic cable would feel like, considered the disorientation of shifting between many different screens. Our current collective state of isolation has intensified this experience: we’re at our computer screens to play a video game, laptop screen to watch a TV show, TV to watch a film, on Zoom to do an interview, on a work computer viewing email, on a tablet to check Instagram and Facebook. Everything is disorientating, to the point that all these slippages happen to our memory and our consciousness.

With the exhibition design, we wanted to find a spatial expression of how the Internet and its encompassing technologies create slippages in consciousness, which have in turn shifted the way we engage with the world. There are almost no straight walls; each surface is slanted and very peculiarly shaped to mirror that sense of discombobulation.

FAD I am familiar with the architecture of Sharjah Art Foundation, already so distinctive in its modular quality – the movement from indoor to outdoor as you pass through courtyards, from the white heat of open spaces into the cloistered shadows of galleries housed in traditional domestic buildings. Despite that, I have no idea of the works’ relationships to one another in the unusual exhibition format you describe, no sense of the experience of them as aesthetic objects or events in time. It sounds like the progression and movement through the works is very deliberate – I’d like to try and add a layer to that imagining, can you explain the structure of the exhibition journey?

Omar Kholeif As you approach the square, sound bombards, you encounter shadows on the floor. Unsure if it’s an artwork, you start to move around the corner, then you’re lost. For now, we have kept on the outdoor sound installation so the public hears these unidentifiable sounds. It’s a project by Lawrence Abu Hamdan called A Convention of Tiny Movements (2015-Ongoing), which we began together for the Armory in 2015. I believe he started the project in late-2014 where he discovered work at MIT around “visual microphones” – devices that can record and then recreate your voice based on micro-vibrations caught visually by high-powered cameras.

There are six different sounds – sometimes discombobulating, sometimes thunderous and piercing. Taken from quotidian, innocuous objects like a rose petal, a tissue box, a packet of crisps, they invade the public space beyond the exhibition as well as the first steps into the galleries themselves. From there, you walk right into the first gallery, another piece from the same series confronts you. It is a picture of a supermarket in Beirut, and the shelves are colour coded depending on which items would be able to record your voice with this technique, and which cannot. From the get-go, you’re immersed in anxiety, immersed in the idea that your passivity is complicit in a world that is somehow always watching you.

You’re then confronted with a quiet and intimate moment through a work from Trevor Paglen‘s “de Beauvoir” (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) (2019) which is a very spectral and ghostly portrait that sets the tone for the show. This is part of a series and is an image of the seminal French writer and thinker but subjected to the Facebook facial recognition algorithm. Paglen argues this is the most powerful in the world. It works by accumulating multiple images of our faces and then creating one “face” that is utterly unique to us.

FAD In the context of the exhibition, I find this work striking for being highly specific and totally general – it is an approximation and it is distinctive. That tension of contradiction feels present throughout. It feels very much like individual consciousness and experience now, always caught in the alienation of technology, no matter how attentive or personalised that might feel on the surface.

Omar Kholeif Though I wish people could see the exhibition, I’m also aware that the Coronavirus and the way that it has spread is a kind of metaphor – we use the word viral in technology as a good thing, yet it’s obviously not in medicine or science. It also says something more nuanced about shifting consciousness, our attachment to everyday technology has been enacted and mirrored by the lockdown. I do not know anyone that is not intertwined with their devices. No one can even recall where they gleaned a piece of information. So, in a way, it’s a map – what we’re in now is a kind of manifestation of these ideas, maybe I shouldn’t be disappointed…

Installation View: Siebren Versteeg, Daily National (Performer) (2019). Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic.

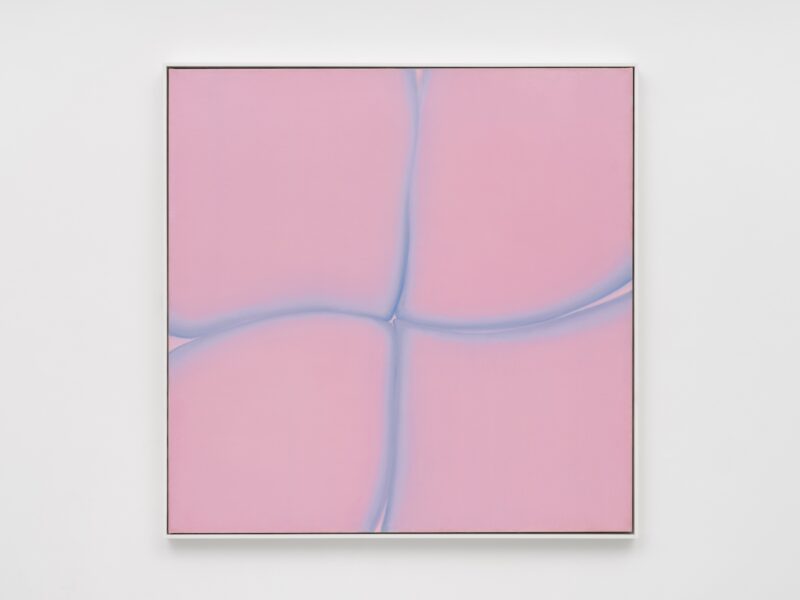

FAD It does seem extraordinarily prescient. I’ve been thinking about the silence and the muteness of the works, existing without witness in the exhibition. For example, Siebren Versteeg’s Daily National (Performer) (2019), where the front page of the UAE’s major English language newspaper The National is being drawn over via computer-generated colours and shapes, every day, without being seen. It heightens this sense of a cancelled future: the news halted, the same story played on repeat like a glitching record, the facts glossed over and over again into a strange abstraction of time distended by one unending story.

Omar Kholeif There are a number of “living” works that are not being seen. Siebren Versteeg’s piece creates a painting based on the cover, then it refreshes. Each day, it is making new paintings and new configurations that we will never witness. That idea of concealment is kind of sad and makes me wonder: how do we hook up these things to other spheres where we can see and engage with them?

There’s also a piece called Drinking Bird Universe (2018) by Tabor Robak, which is meant to look like an iPhone screen. On it, an algorithm creates a series of shapes, abstractions of alarming and anxiety-inducing headlines with information pulled from different RSS feeds.

It’s a work about the bombardment of information. It’s fascinating to me that, while we are at home, locked down, being inundated with information, there inside the exhibition, the walls and the security guards are also constantly bombarded, witnessing this unending stream of fear-inducing headlines through the artworks.

FAD Thinking about “witnessing” – I’ve been finding the way people are using Instagram lives so compelling. This experience of peering into people’s homes, their bedrooms and lives, witnessing something relatively unrehearsed – there’s something so intimate in these encounters, an immediacy that feels remarkably different than our usual acts of social performativity, the perfecting of stories and newsfeeds.

I’m thinking about this in relation to Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s work; just as the goods are colour-coded into those that hear and those that cannot, we exist with two contradictory anxieties: the fear of being “un-witnessed” and the anxiety of being surveilled. Anxious of being recorded, we also have a creeping sense that we may not exist if we are not documented.

Omar Kholeif We’re stuck because we have already become accustomed to the conveniences that these technologies offer, we’re incapable of standing back and reflecting on the reality. So, we have a sense of complicity. But what are we doing to our brains? They’re totally encumbered, yet we’re doing it without pause, failing to interrogate the process.

Even if we are in a position to multitask, I don’t believe that these things are necessarily healthy. Critics like Nicholas Carr said very early on that the Internet is completely ruining our potential to read and recall information. People like Hans Ulrich Obrist, Douglas Coupland and Shumon Basar, have said that Google is now our brain, our memory bank. I believe this to be true, but I don’t think it’s necessarily always a bad thing; it enables us to be more productive and do the things that we want to do. But in moments of crisis, where we’re seeking comfort, solace, retreat, I think over-dependence creates such intense stimulus and anxiety that it prevents us from living healthy lives.

One clear example is that I don’t sleep – and that’s because I’m wired on technology. I don’t want to say it’s become like a drug because I hate that metaphor, it’s so archaic now. But it has become almost nutritious, like food. So, I wonder how we might move out of this situation to be more reflective.

That’s what the exhibition tries to achieve, to create moments, singular moments, where you stand and become very reflective. So, when you stand in front of Trevor Paglen’s Circles (2015), which is a slow, meditative video of the GCHQ building in Gloucestershire, documented in a very quiet, delicate, sci-fi way. The projection is enormous but directed into the diagonals of corners, so you feel as if you’re falling into the circle. It creates a space of quiet repose, but you know that something creepy lies beneath, and it implores you to go and question that.

FAD It seems the exhibition is structured by dissonance, creating contrasts or strange resonances. Is that to call attention to what is overlooked?

Omar Kholeif Yes, there’s a desire to show how things that are actually quite dangerous and scary are becoming very quotidian. For example, right next to Paglen’s Circles is Wail that Was Warning (2018) by Aura Satz, another circle that you pull, that triggers a siren. The sound gets progressively louder and louder, it emanates throughout the exhibition, disrupting the very silent nature of works like Paglen’s film. It calls attention to how we’ve all become so used to death, living in urban environments. Accustomed to the sound of sirens, and to the anxiety they induce, we are no longer able to recall or engage with the specificity of what they mean.

FAD I feel that complicity is so apparent in the steady normalisation of data gathering. For example, conversations around Coronavirus track and trace apps, there’s an inevitability to it. Though everyone has a much greater analytical capacity to question how it is going to surveil us, how our data is going to be used, it doesn’t necessarily shift the response in any useful way. It’s normal dialogue, except when it is distorted into conspiracies, which seemed so outlandish, pure farce, yet are now making their ways into mainstream media.

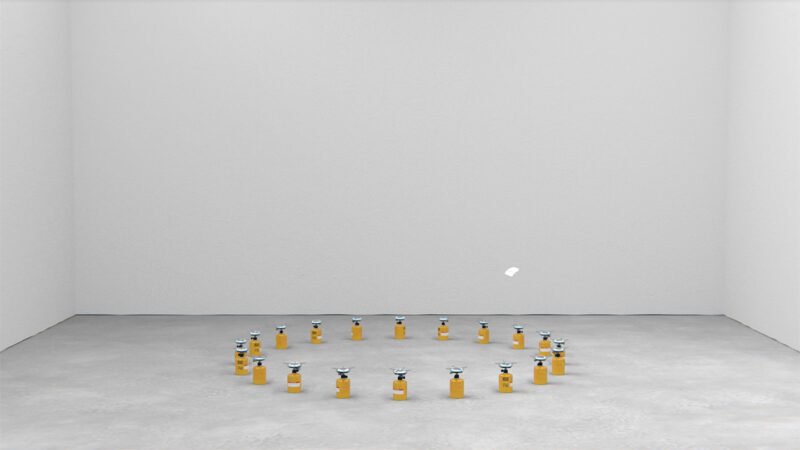

James Bridle, Homo Sacer (2014). Installation View: Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Danko Stjepanovic.

So there is an insidious and gradual acceptance bred through familiarity – as if knowledge is enough. That’s the uncomfortable experience of James Bridle’s Homo Sacer (2014), the progressive morphing of the fundamental right to citizenship. A concatenation of micro shifts that facilitate the next, moving us progressively away from what would originally have been unimaginable.

In terms of this progressive shift, in relation to this exhibition, Douglas Coupland has written about a sense of the future being displaced, he writes “The future used to be in the future, but for years we’ve been getting closer and closer to it, and now the present and the future have become the same thing”.

I have a strange, probably naive, hope about this extreme moment of pause. I wonder if this collision with the ‘end’, a sense of a future that has been “stopped, the noise of contemporary life postponed – could allow us to think through things differently? In this forced, collective experience of “cancellation” do we find a potential space to reflect on what we have accepted? Here, can we contend with what has felt too fast to linger over, the acceleration of tech and consumption and politics and news?

Omar Kholeif I don’t necessarily agree – I think that Douglas’s point in that essay, which features in the catalogue for this show is a very prescient point and a very interesting one. But I think what you’ve just articulated about an almost cyborgian interdependence on technology leading to our ultimate destruction is an accelerationist view. Personally, I choose not to engage with that, I think if I did, even just as a human being, let alone as a curator or cultural historian, I would cease to find my own agency to speak.

Now, a lot of people are digital dystopians – I have always said I’m more like a digital centrist, sometimes even a digital leftist. I think the really pivotal question that lies ahead is how we will reintegrate into society, especially in fields of practice that demand proximity to other people. I think, for the time being, we should accept our interdependence with technology while being wary of how we use it.

To think about it in a purely dystopian way is unhelpful for me. I don’t think we should come to terms with the idea that technology will ultimately destroy our lives, that our only option is to live with it and be with it until it eventually eats us alive. If we do, we start to enact that reality, and I don’t want to mirror a machine.

Find part II of the conversation here.

The exhibition is open to the public from June 26 – September 26 202o, at Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE.