Ex-Delfina Resident Asunción Molinos Gordo explores the inequalities inherent in the global food system in her first UK solo exhibition Accumulation by Dispossession. Curated by Dani Burrows.

Asunción Molinos Gordo, ‘Accumulation by Dispossession’, 2019. Exhibition at Delfina Foundation, 30 Apr-22 Jun 2019. Photo Tim Bowditch. Courtesy Delfina Foundation

Molinos (b.1979, Spain) questions the categories defining “innovation” in mainstream discourses today. From the urban to the rural, from Turkey to the UK, from video to ceramic, she investigates and exposes the reality behind the food chain. She is particularly interested in unveiling all those details we cannot see, or simply ignore, such as who decides food prices, who has access to what is produced, where and how food is distributed. The artist is driven by a strong desire to understand the value and complexity of the rural, and especially its cultural production and the obstacles that lead to its marginalisation.

In 2014 Molinos was a resident at Delfina Foundation, taking part in the first iteration of The Politics of Food thematic programme. This year she is back at the foundation bringing to light her research. The title, Accumulation by Dispossession, is borrowed from the work by the Marxist Professor David Harvey. In his 2003 book, The New Imperialism, Harvey introduced the concept to describe the increasing feature of global capitalism to concentrate wealth and power in the hands of the few through the process of dispossession. During her 2014 residency at Delfina Foundation, Molinos related this concept to her on-going research into the food system, the outcome of which is this exhibition.

Asunción Molinos Gordo, ‘Accumulation by Dispossession’, 2019. Photo Tim Bowditch. Courtesy Delfina Foundation

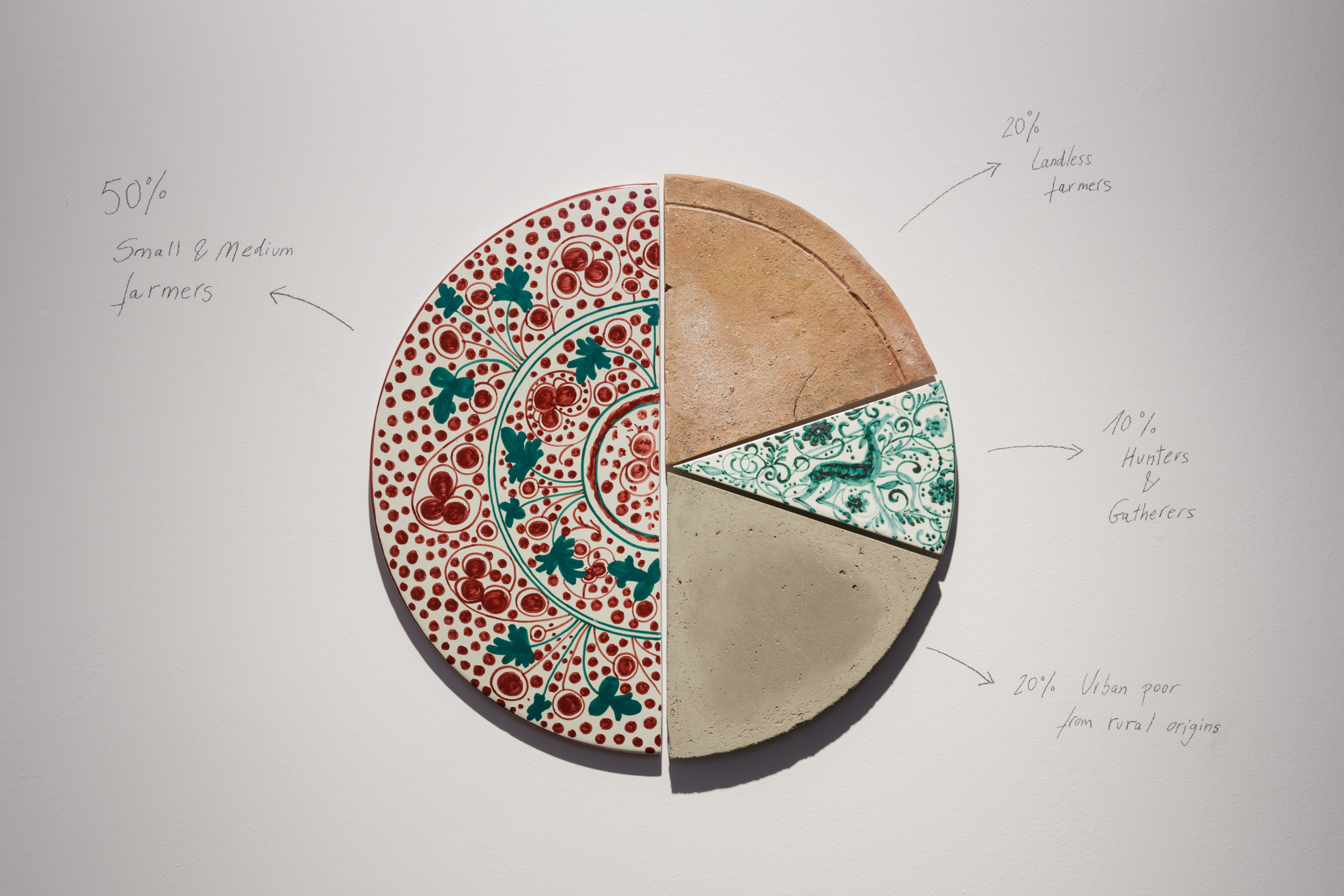

The show is dived thematically, where works explore different questions of privatisation, financialisation, the management and manipulation of crisis, as well as redistribution. How is food traded? What happens to food when it leaves the hands of the producer? And why does this create such an unbalanced and unjust situation? As soon as visitors descend Delfina’s staircase, they are welcomed by a ceramic-made statistic circle. The beautiful porcelain, painted with harmonic flowers and young deers, do not recount an equally pleasant scenario. While food is in the main produced by small and medium farmers, they are also the ones more likely to suffer from famine. I should also say that this discourse becomes even more disquieting when it comes to gender. As reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), if women were granted equal access to resources as men, the victims of hunger worldwide would decrease by up to 150 million people. So, who is the hungry? Farmers themselves; by and large women.

A similar analysis taints the story of seed ownership and production in Turkey. In a 18 minutes video produced for the Cappadocia festival in Turkey, the artists gives voice to an ongoing debate between local farmers. In a small cafe, a variety of people is interviewed, obviously with a çayi in their hands, the typical Turkish tea you see all people drinking, at any time. This Anatolian region is particularly affected by a recent production law which dispossessed producers from having control on their crop and seeds. In Turkey, albeit its rich biodiversity, farmers have no control over the national seeds. The World Bank Agriculture Reform Implementation Act (2001-2005) forced land-owner to adopt a market-driven model, introducing foreign seeds, for example. The 2006 law accepted by the Turkey’s Grand National Assembly obliged farmers to chose their crops only based on their yield-efficency, completely ignoring the value and variety of adaptability. Local seeds entered a black-hole, leaving space for anonymous (but potentially economically profitable….for the government) harvests. Interestingly, this law is not perceived as harmful by everyone, with a dispute been shown on the camera between traditional farmers and looking-forward ones. Yet this law also introduced a series of norms causing evident financial burdens for small farmers.

Not only do producers have no control over the physical byproducts of their work. They generally have no say on the pricing process either. They are price takers, not givers. Why are farmers not able to negotiate the food prices? Because, we know this, big capitals rule. The prices for the basic and most vital crops (wheat, rice, corn, soy) are determined by the Chicago Board of Trade, in US dollars! Clearly, small and medium-sized producers in areas where the monetary value don’t keep up with the North American one struggle to have an income. What they make from selling their harvest is hardly sufficient to grant them money to live. The food is bought from the big traders. And they have the capacity to decide the price.

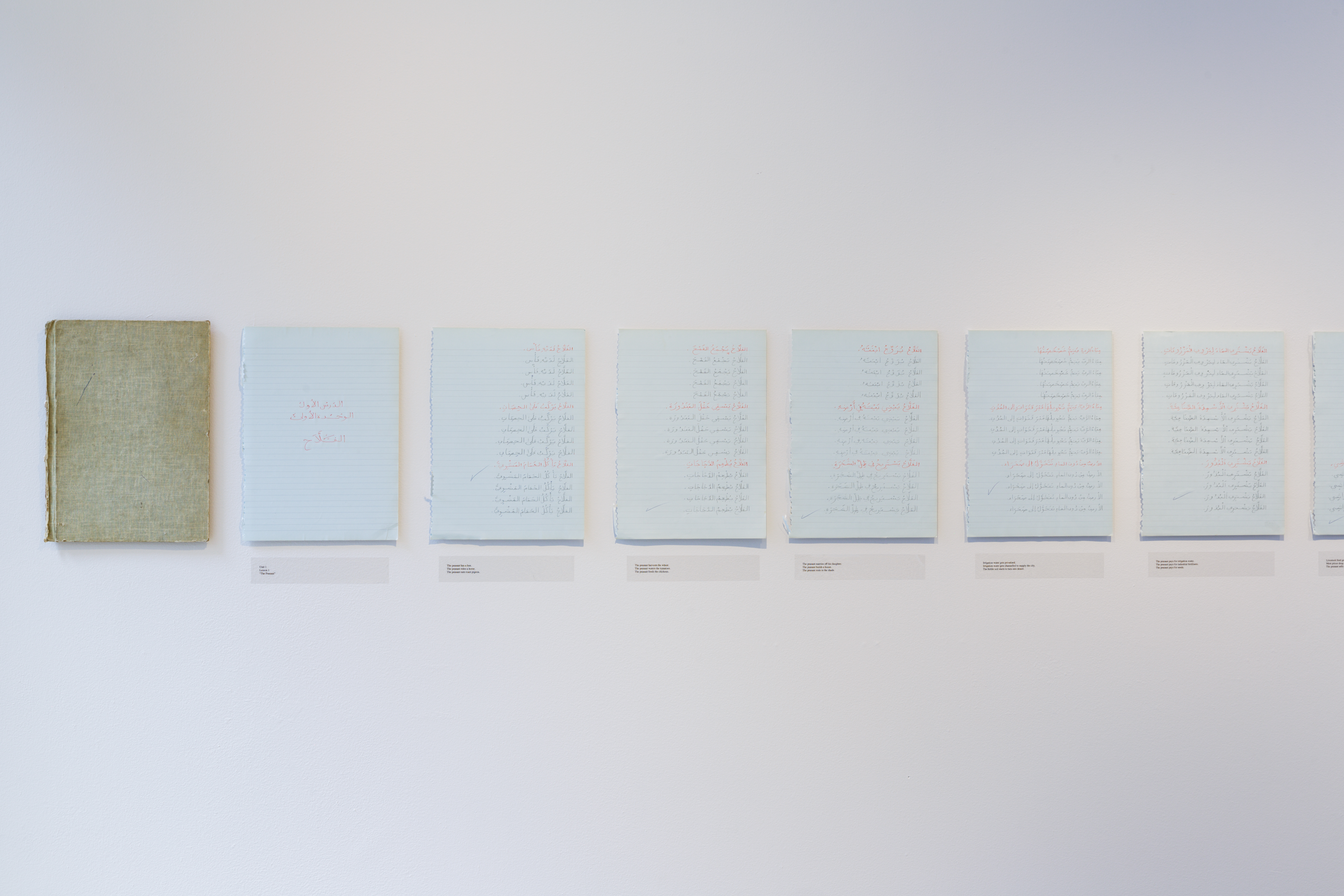

All these dispossessions go highly unacknowledged in the open air. Molinos recognized this while learning arabic. At a course, the teacher had her write the same sentences over and over again, in order to familiarize her with the alphabet and calligraphy. Recurrently, she found herself noting sentences like ‘The peasant has a hoe,’ ‘The peasant eats roast pigeon.’ Clearly, this written reality did not equal what was going on in real life. So Molinos started writing her own sentences, showing how ‘Irrigation water gets privatized,’ ‘The fertile soil starts turning into deserts.’ ‘The peasant pays for irrigation water.’

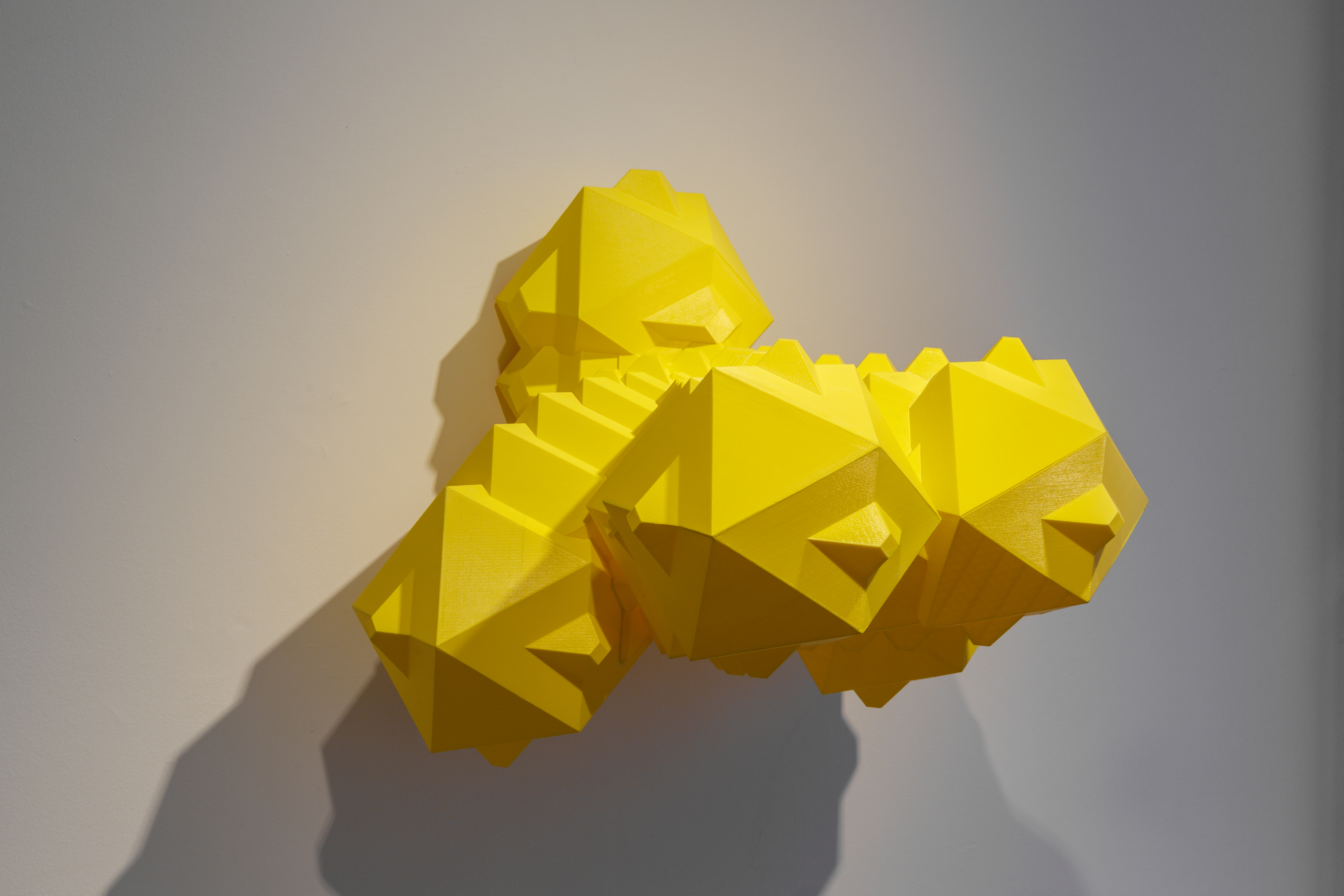

Using a variety of media, including drawings, videos, sculptures, photographs and textiles, the works are a combination of hand-made, machine assembled and computerised, reflecting the different inputs and influences within the food system itself. Power has to do with not having access to food resources, not merely with producing it. Food scarcity? NO! There’s a lot food. It’s all about food distribution, accumulation, displacement. There is enough food to feed the world. And yet famine seems a never-ending issue. The criticality lies in where does the food go. It’s a hourglass system, as Molino draws on the wall of Delfina’s space. A lot of producers, a lot of consumers. But who decides stands in the middle: a very small group of people. This is central to understanding the difference between dispossession and accumulation.

Molino’s eclectic combinations of medias and discoursed manages to show to a full extent the series of manipulations and injustices engendered by an unequal distribution of food. Dispossession, as Molinos evidences, is the depriving of the lands from their rightful owners. It’s a dispossession of water, knowledge, work, pricing capacity…

ASUNCIÓN MOLINOS GORDO: ACCUMULATION BY DISPOSSESSION until 22nd June at delfinafoundation.com