Heather Sincavage is a performance artist, educator, and curator. Her works often use food to make trauma visible, and heal through it. She will perform in Riga Performance Art Festival: Starptelpa in June (details to come!).

Read my interview with her. Get to the very end! There’s a special surprise the artist so kindly shared with me (and you).

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018. Image by Adriano Farinella

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018. Image by Adriano Farinella

Sincavage recurrently uses food in her work. The performances To Have, To Hold and Pangs Of are a case on point. All dressed in white, she sat on a chair, or on the grass, for hours. She was holding out red berries to the audience. Time passed, and her offers remained unreciprocated. With time, the juicy gifts stained her gown. From candid to bloody, the passage was fast.

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018. Image by Adriano Farinella

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018. Image by Adriano Farinella

A simple gesture, a basic donation, turned out to reveal the fragile nature of generosity. Raspberries, the most prevalent fruit in the performance, signaled a symbol of fragility and kindness, already pointed to this duality.

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Hector Canonge

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Hector Canonge

The suffering coming from the unreciprocated generosity was only a remote echo of a deeper trauma that characterizes the artist’s work (and personal history). An offering is never just that. Signifiers have no simple, unique signified. The artist was offering herself, was exposing her interiority to passerby. The deep red of these fruit permanently tainted the white cloth of the her dress, indicating the lasting effects of intimacy.

The more the viewers decided to remain that–viewers, rather than participants, the more Sincavage’s provoked them. In an ultimate attempt to not let the berries slip away, she folded the skirt up on her body. Unavoidably, this left her genital area exposed. With the red juice staining all over, a reminiscence to taboo-menstruation, hymen-breakage and pain seem inescapable.

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Hector Canonge

To have, to hold, 25 minutes, Nexus PAF during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Hector Canonge

For Pangs Of I’ll leave you the artist description as she sent it to me. I really feel I cannot use better words that the ones she chose:

This one-hour seated durational performance is a repetitive offering from the performer to audience. The performance is an act of holding 300 quarts of raspberries on (and spilled over) her lap. A small group of 5-6 raspberries is placed in her mouth, masticated, and then offered to the person sitting across from her, then repeated. The participants can choose to eat the fruit offered or reject it. Should no one be sitting there, the performer will still masticate the fruit and offer it to the empty space. The rejected/unaccepted fruit is disposed of onto the floor.

This offering is an act of kindness. Kindness, an act thought to be of the heart, is historically represented in art history by the raspberry. The heart is known to pump 2000 quarts of blood per day or 300 quarts in one hour. The length of the performance is determined by the amount of fruit offered. The fruit, however, is also considered fragile and therefore this offering and all of its implications can be thought of as a fragile exchange.

The performer will be wearing a white garment while holding the fruit. It is expected that the fruit and its juices will stain the garment, indicating the lasting effects, both good and bad, of intimacy. At the end of the hour, the performer will gather the rejected fruit in her arms, hold it against her body, and leave the performance area. Again, it is implied that the rejection is carried within us and has lasting effects.

Pangs of, 1 hour, Alive at Satellite, Satellite Art Show during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Alex Sullivan, courtesy of Performance Is Alive

Pangs of, 1 hour, Alive at Satellite, Satellite Art Show during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Alex Sullivan, courtesy of Performance Is AliveAs I said before, this unreclaimed gifts are only the public, visible reverberation of a deep trauma. Having suffered intimate partner abuse, Sincavage’s performances work through this trauma. They don’t simply heal it, in a cathartic way. You never heal. Marks, scars, painful memories won’t go away. Yet, by exposing the trauma, you make it visible for the audience, but also for you. Food is highly mimetic. It’s organic, like a body. It warms to your hands’ touch. It perishes. These quality makes it a perfect agent for re-enacting, visualizing and reflecting on trauma.

Pangs of, 1 hour, Alive at Satellite, Satellite Art Show during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Alex Sullivan, courtesy of Performance Is Alive

Pangs of, 1 hour, Alive at Satellite, Satellite Art Show during Miami Art Week | Art Basel, 2018; image by Alex Sullivan, courtesy of Performance Is Alive

Here is my interview with the artist.

- Hi Heather, so nice that you can take part in my project. I would like to first have you introduce your performance work. How did you start? Why performance?

I’ve always considered myself an “interdisciplinaryartist” working with themes that involve rebuilding my life after intimate partner abuse. For many years, I worked in sculpture, drawing, and installation. As much as I tried, I always felt as though the work felt stagnantand that the figure lacked the autonomy I intended to create for her. At a residency, about six years ago, I had a very meaningful discussion with another resident about how I was representing the body. That small discussion led me down this rabbit hole that eventually became performative. I didn’t make a definitive choice to do performance work. It first came as a way to document drawings I was creating at the time. After watching, I was more intrigued by the making of the drawings than the drawings themselves and from there, I began to consider gestures that were not drawing-centric. Performance emerged as a way for my body to make a mark and be completely in control of its image. It further became a way to connect with an audience in a way my still work hadn’t. I tackle heavy themesand have struggled to find an audience who weren’t fascinated by the mania of my early work’s construction. Performance has become a more direct avenue for meaningful conversation. Additionally, I find that the structure of my performances is more focused, and sparer. Every movement, material, shape, etc have intention. I’ve eliminated the clutter that was prevalent in my still work in exchange for a direct “conversation” with a viewer through performance.

- You often use edible elements, such as berriesor lard. How did this come about? What attracts you about the use of comestible material? Is it its analogy with the body? Its quick perishability? Its socio-cultural implication?

Materiality is very important to me. What I choose to work with is very symbolic. I am always looking to make a reference back to the body and its experience living with trauma. For many of my pieces, I use a form of measurement, usually weight, as it would relate back to the functions of the body. Examples from a few of my works are: a 10 ounce stone = the human heart, 300 quarts of berries = the amount of blood pumped through the heart in one hour, 180 lbs of manure = a human body.

Each of these materials were chosen for their symbolism and how they imply the body. I feel it is best to use a material we already have a close relationship with because we understand it and have our own associations coming from our experiences with the material. For me, then to use it as I do in my performances allows an entry point into understanding the work.

- It seems to me the food you choose is highly symbolic. The berries in to have, to hold quickly stained your immaculate, white dress. Immediately, juice turned into blood. A blood which not only referenced female’s stigma, but also the pain resulting from a non-reciprocated intimacy. The lard directly dialogued with your body, mirroring and healing trauma. Can you tell us about your relationship with food? How do you choose the elements? What do they signify?

There is both a practical and symbolic reason to use food. First and foremost, we all have our own associations with food and is readily accessible to work with. Furthermore, there is a strong tradition of food in art history. I do look upon food symbolism historically to help inform what I am doing. In fact, the berry work emerged after teaching a class where we discussedvanitaspaintings.

I am also looking at these foods for their plastic properties as well. The berries were especially important because not only are they precious, they are also fragile. In early Christian artwork, raspberries have been represented as a symbol of kindness. In “to have, to hold” and a related piece “pangs of” the berries begin whole, as an offering that is often not reciprocated, but, as the performance continues, they break down into pulp/juice that stains me and my garment. These pieces are about an offering of myself to another. But furthermore, they explore the connections of intimacy and power dynamics within that intimacy. The stain the berries made is equally important because as we move on from our relationships, our experiences shape us, create how we interact in future situations. In those two pieces, the stains are impossible to consider that they would ever be removed from the garment, just as my experiences with trauma will always be with me.

- I could’t help but think about the highly aesthetic impact these edibles have as well. Do you think about it when conceiving the artwork? Or symbology comes before, and then everything else follows?

I have set up a few parameters for myself. In whatever I am looking to do, my outward gesture should imply an inward function of the body. That inward function therefore explores the emotional impact from trauma. It’s taken me a number of years to be okay with this. I first made very gruesome work reliving trauma, then spent many years trying to heal and move on. I now have come to accept it as a part of my life that will always be with me. I am looking for a better understanding of myself. This might imply a bit of navel-gazing but my experience is not unique. In a 2016 report, 75% of young women have reported an experience with sexual harassment and assault, during their college years. This trauma is far too prevalent in young women to not examine it. People often tell me how cathartic that must be to make my work, that I’m strong for working it out the way I do, and these comments always bother me. I am really trying to intellectually understand trauma so that I can manage my life and empower others. It isn’t necessarily cathartic- I will always hurt. But a better understanding as to how complex the situations I got myself into might allow better understanding and even a more empathetic treatment of people enduring trauma. At the time, people close to me either chose not to believe me or swept it under the rug. I believe much of that behavior manifested in my body to create legitimate health concerns- such as chronic illness, such as cancer, such as changes in my body. For a current project I’m workshopping with the lard, I read one source of lipomas comes as a result of physical trauma. I can’t help to think of being assaulted by my partner when I was strangled, punched, and kicked. It struck me that huge lump I have on my back is a result of the many years of carrying this experience around with mean my body then literally created an armor to protect itself in this large lipoma. So, in using lard, I am exploring subconscious armors we build for ourselves.

All in all, the material I use is incredibly important. Sometimes the material comes first but other times it’s the gesture. If I am to be honest, the first berry piece, ‘pangs of,’ probably began as the gesture of chewing food and offering it to people but with the lard work, I definitely began with the lard for what it represents.

- In my research, I am trying to question the equation between domesticity / cooking and femaleness. Patriarchal societies passed this a natural law, and this generated an enormous gender (and also class and ethnical) disparity. How do you feel about this? Were you somehow influenced by a need of breaking boundaries between home and public sphere?

When I first read this question, I had to laugh because I actually really hate cooking or figuring out what I should eat. My partner does all the cooking.

On a more serious note though, I am thinking about labor and as my work has been progressing, I am thinking about “women’s work” so clearly as intimate partner violence is primarily (but not exclusively) a women-centered issue. I am interested in intersecting (for lack of a better term) gender-specific labor with the cognitive labor women contend with while living with trauma. It is maneuvering triggers, battling depression, negotiating social situations, not to mention all the direct emotional work cleaning up from the immediate aftermath. Trauma is felt in the body and, often, when I deal with weights in my work, it is because I have felt the emotional weight in my body.

Labor is a theme I don’t think I have developed in earnest as of yet, it has been more a secondary component. The making of my performances involve a tremendous amount of labor. My recent ash performance, ‘2375,’ required days of burning wood, sifting ash, and then, after the performance, hours of washing all surfaces in the room, myself, then the bathroom I cleaned myself in and all items embedded with ash then laundered, dried, and folded. It felt like endless days of this performance when the actual piece lasted 4 hours. I’ve joked that I am an artist – scullery maid.

But I do believe there is something to this- the maintenance of the self and how we compose our self to be in the public realm requires an exorbitant amount of care and energy of the internal self. I do not think people want to recognize that about mental health, especially as the years wain on.

- Do you consider food to be empowering? Can it actually bring a certain entitlement to women once it is brought into the public dimension?

That’s a good question. When I perform, especially during the recent berry pieces, there has been an amazing charge I have felt in using the fruit, especially in the scale I chose to use it. “To have, to hold” and “pangs of” are both about offering on my terms. While much of the offering is unreciprocated, I deem this as the “others” problem, not mine. These were pieces where, for the first time, I felt in command of the space rather than entering from the periphery to potentially be ignored. So, from my experience, it is incredibly empowering.

Overall, we can’t ignore the associations a viewing audience will make. Despite how far feminism has come, patriarchy still exists. However, how can we ignore how food has been used by women to challenge that? Think Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy. Nao Bustamente’s Indigirrito. And endless others. Women are challenging stereotypes with material often associated with them, food.

- So, we’ve established that, for better or worst, food is a domestic (aka feminine) matter. Clearly when women use food as an artistic vehicle it’s hardnot to read a subtle critique of that equation. Yet food brings also a familiar unity through the generational passing down of recipes. Can you share a recipe that is meaningful for you?

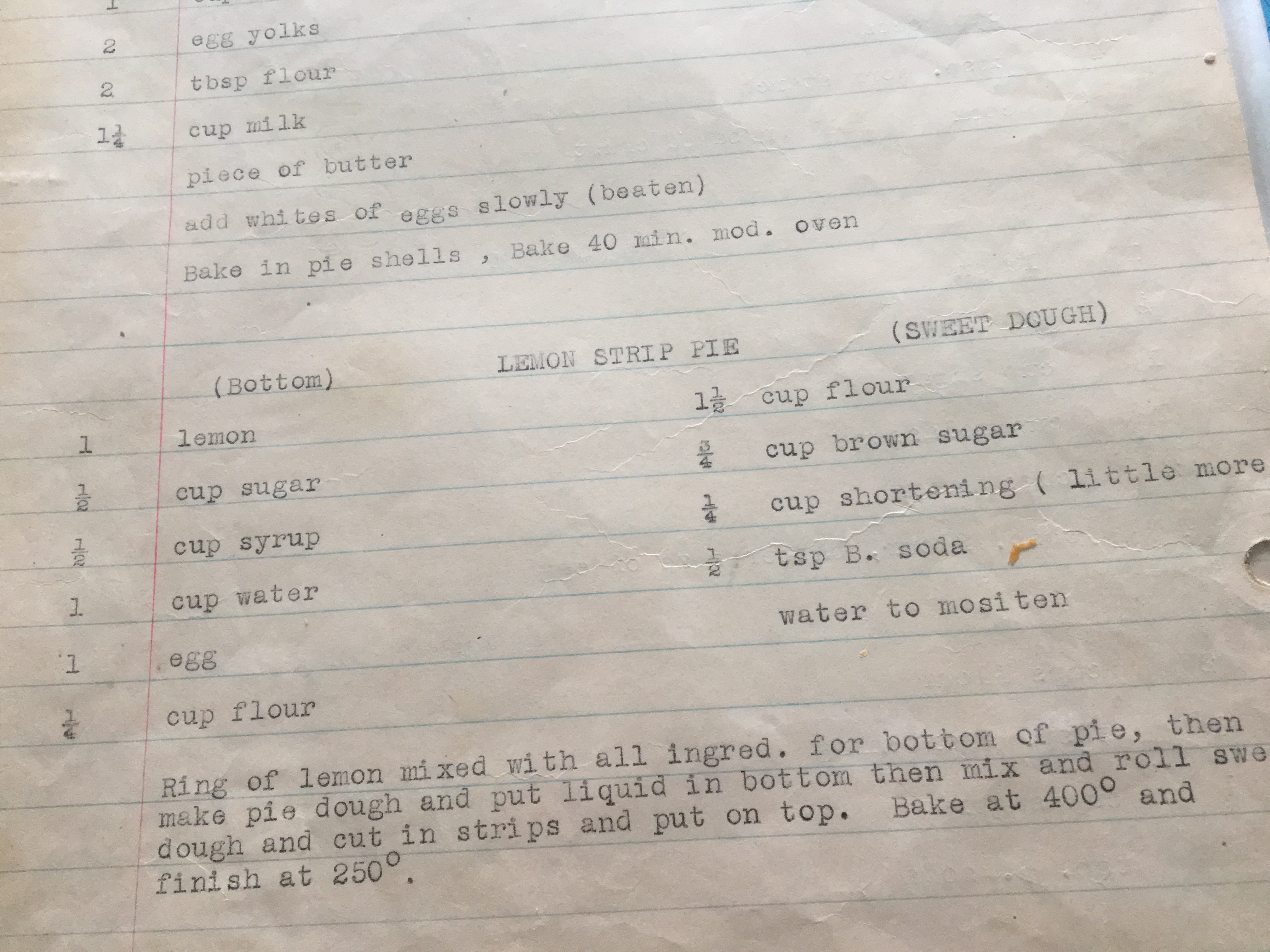

Here you are! From my great-grandmother!