Liverpool Biennial 2018 Liverpool Biennial, with 40 artists from 22 countries, steers clear of the standard offerings: there is no central hub; no big ‘wow factor’ work to provide a talking point; and far less use than in previous editions of unusual locations, preference being given to exploiting the existing infrastructure of public arts buildings – so no ‘wow locations’ either.

Perhaps the idea is to call attention to Liverpool’s improved infrastructure, which is also sufficient to swallow such major parallel events as the John Moores Painting Prize, Bloomberg Contemporaries and a celebration of current art from Shanghai. That thinking extends to foregrounding existing collections, such as the World Museum’s impressive papier–mâché flowers. And the theme – Beautiful world, where are you? – is pretty loose, allowing for regret for what’s gone and optimism for the future. The result is a quietly democratic and thoughtful Biennial experience, with many of the best work too old to have been influenced by the event: three artists to whom I warmed were in that category…

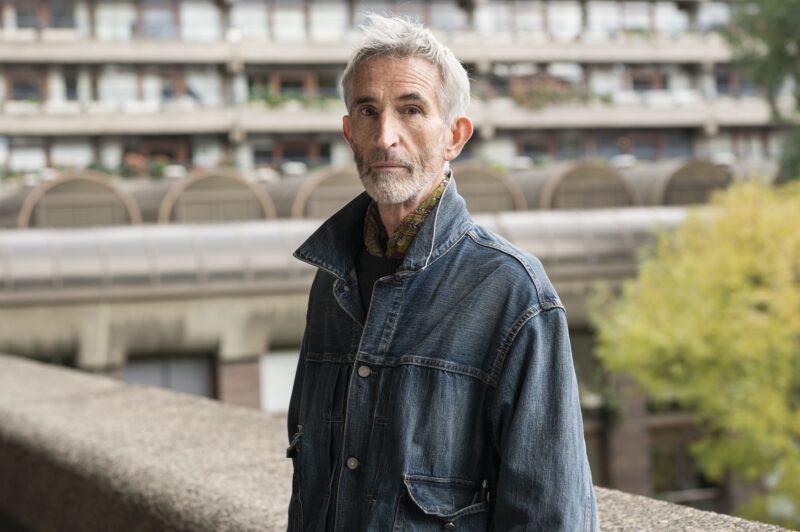

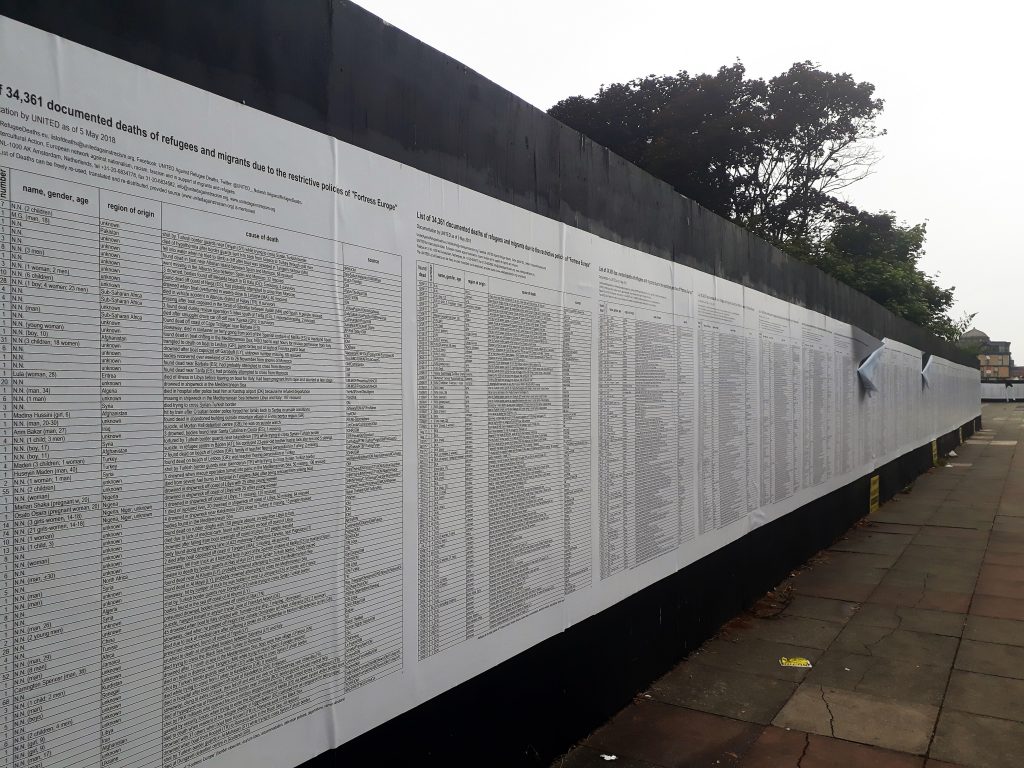

Banu Cennetolu

The Turkish artist, who is also showing at the Chisenhale currently, doesn’t necessarily see The List as art: her purpose is to draw attention to the fate of over 34,000 asylum seekers who have died since 1993 in trying to enter Europe, or within the system for detaining them. She re-presents internet-sourced data to maximise its visibility, here by showing what’s known of date, name, origin and cause of death on a massive advertising hoarding (you can also read the distressing litany of drownings, security force shootings and suicides in detention here). It led to something of a fly posting war, as prior users of the site pulled down sheets, which then had to be replaced.

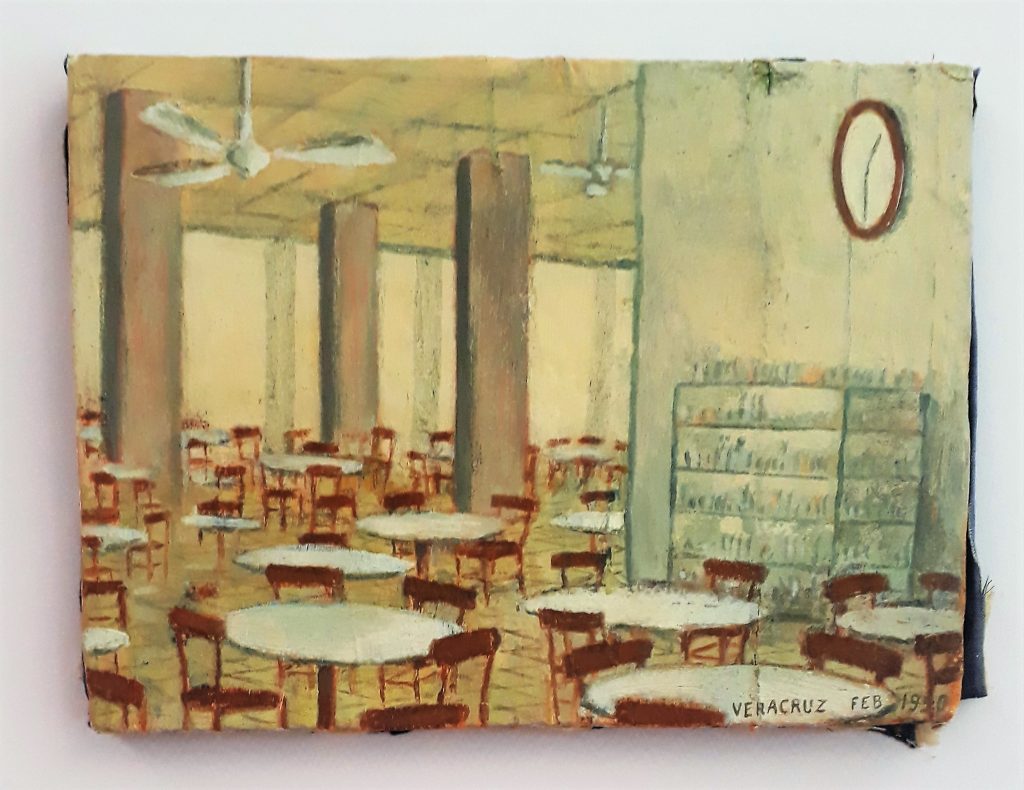

Francis Alÿs

One modest room in the Victoria Museum is ringed with postcard-sized paintings which the Mexico City-based Belgian has made plein air in the course of travelling to conflict zones to make his renowned film works. And the hauntingly light touch of the paintings in Age Piece is presented as a means of self-discovery by the wall labelling, which sequences them according to how old Alÿs was – from 22 to 59 – at the time of their production.

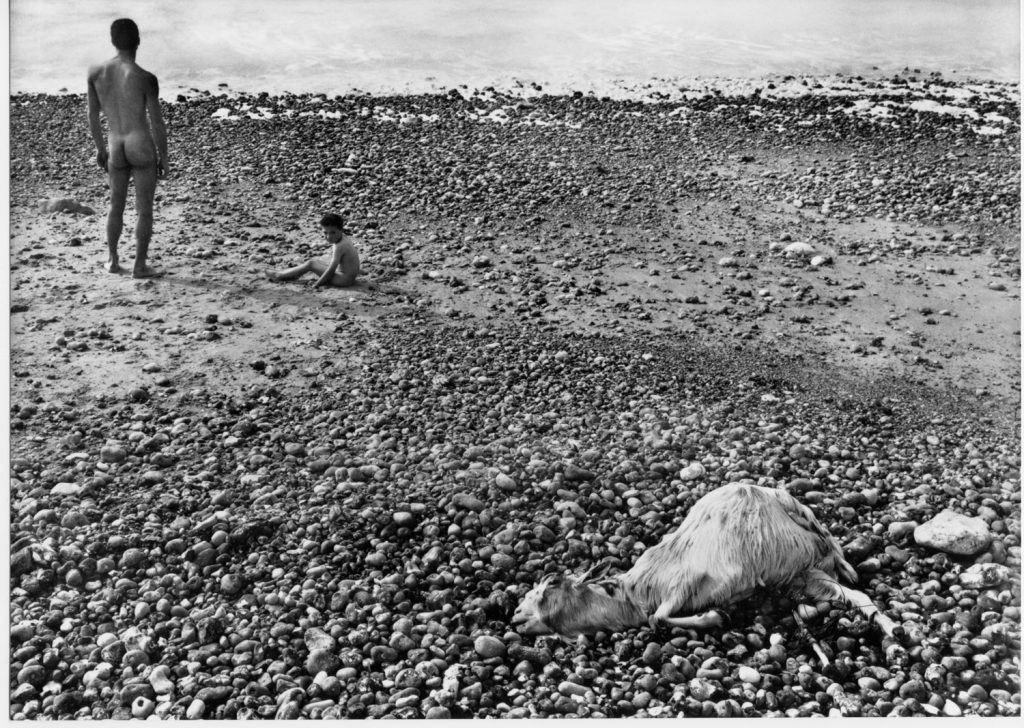

Agnès Varda

The veteran French new wave film director has shown regularly in galleries this century. At FACT she combines a monumentally-sized new photograph with a three-screen installation of extracts from previous films, and the beautifully nuanced 1982 short Ulysses, in which she tracks down the subjects in her own photograph from 1954 to inform voice-over reflections on the nature of images and the effects of memory. In a subsequent Q&A, she majored on her passion for heart-shaped potatoes, beaches and cats – which she admires for how people love them but – unlike dogs – cannot tell whether they love them back.