On the eastern front in 1944, rear gunner Joseph Beuys (b1921-d1986) was—according to his own personal mythology— rescued from a burning Stuka by Tatar nomads and wrapped in fat and felt. These totemic materials predominate throughout the German artist’s work, with the myth as a resonating centre of meaning, both personal and historical, even if the story itself isn’t really true.

Curated by Norman Rosenthal, who worked with Beuys on many shows from the 1970s, Galerie Thaddeus Ropac has brought together a representative selection from across Beuys’s career. The show recreates part of Beuys’s 1982 Berlin exhibition ‘Zeitgest’ giving us a unique chance to review may of the Beuys’s key ’Stag Monuments’. It doesn’t add any huge revelations to our understanding of Beuys but is a reflective illustration of his rough-edged iconic work, which still sits uneasily within an art machine devoted to shiny things.

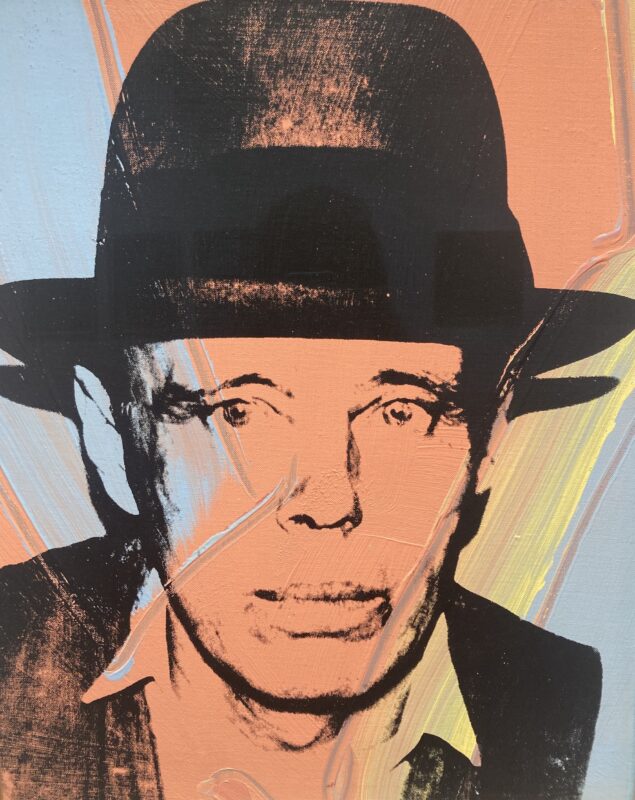

In the plush marble-lined corridors of Ely House in Mayfair, the unfinished sense of pencil sketches and workings on blackboards sets off an uneasy relationship with their surroundings, not least with titles like KUNST=CAPITAL (1983) and Economy and Socialism (1980). These point to Beuys’s continuing status as the Utopian thinker of the view that ‘everyone is an artist’, even if he has been adopted and sanitised as a household name. La rivoluzione siamo Noi (We are the revolution) (1971), a life-size sepia silkscreen of Beuys at his most iconic, striding forward in his trademark hat, gives a clue to his cowboy-like appeal, as a self-styled pioneer at a frontier in art that has by now seen plenty of action.

Infiltration-homogen für Cello (1966-85) is a cello wrapped in felt with a Red Cross, symbolising both crisis and salvation. It is literally wrapped up in Beuys’s personal myth, but the grey felt of this and Felt Suit (1970) set off wider historical resonances, not least the uniforms in the concentration camps. Beuys was continually making and remaking the history and war and culture through re-assembling its artefacts. The conceptual sculptures of the Stag Monuments form a kind of spatial poetry leaving plenty of space for individual interpretation. A wall of clip-mounted strips of thick grey felt, and larger mixed media assemblages Kleines Kraftwerk (1984) and Feldbett (1982) combine degraded copper wire and electrical accumulators and batteries with the grey felt—typical Beuysian intersections between the vulnerability of both flesh and material.

Nearly four decades on, the intervening digital revolution has given these assemblages a kind of steampunk feel: rusty metal boxes, a standing camera ossified into rock, slate workshop tables, scatterings of half-made pebble-like stones. There’s a coffin-like rock, an open box of rolled felt and yellow margarine, a black Bakelite phone wrapped in straw and mud, cumulatively embracing timeless themes of ecology and machines, social organisms and how we connect through art: perfectly Beuysian encounters between the prehistoric origins of society and art, and the rootless and relentless technomodernism of the twentieth century.

Joseph Beuys: Utopia at the Stag Monuments is at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London until 16th June 2018 www.ropac.net