Blain|Southern gallery in London just presented its show featuring early photographs by the acclaimed film-maker Wim Wenders. It is an incredible opportunity to discover a new side of this all-embracing artist, and to see for the first time some of the polaroids he kept hidden in his archive.

The gallery presents a (small) selection of C-prints, based on original Polaroids taken by the artist. ‘Small’ because, as Wenders himself stated, he gave away the majority of the polaroids to the people inhabiting the places of his photos. Some of the prints are shown in their original, minute size, while others have been enlarged. Big or tiny, they all symbolise the capturing of a moment and have not been altered by the artists in any way. For Wenders, in fact, the essence of photography lies in its authenticity and immediacy, both intended as belonging to an evanescent moment, and to not having being mediated by inorganic action.

We see, as a consequence, pictures where time and light left their unavoidable traces, “ruining” the perfect, dolly-like, smooth surface of the polaroid, as the modern, photoshop-intoxicated mind would perceive it. Wenders kept all of his pictures in old cigar boxes, which allowed the majority of them to preserve quite well. The cases were indeed designed to keep a constant temperature and atmospheric condition ideal for the right conservation of the medium. Nevertheless, some of them, inevitably, varied. But this was not an issue for Wenders. On the contrary, the truth that filtered through this organic alterations was just an added value.

Wim Wenders, Surf City, N. Carolina, (1973), C-print, 60 x 78 cm. Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

Wim Wenders, Surf City, N. Carolina, (1973), C-print, 60 x 78 cm. Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

Looking at this print, Surf City, N. Carolina, Wenders gladly commented: “This is it: it has cracks now, like an old painting.” It all goes back to the idea of spontaneity and powerlessness in front of nature, time, life. After all, you cannot really control the polaroid, you just have to take whatever comes out of the machine. There can be no manipulation, no retouching, no ripensamenti. That is what Wenders appreciated the most of these instant films: their being moments of a moment.

Polaroids also have a very personal connection to Wim Wenders, since they were the medium and format he first used when learning the art of film-making. Not surprisingly, a number of the pictures in the exhibition were at first simply intended as researches for potential sets for his movies. In spite of their primary objective, those little, squared pictures turned themselves into something much more powerful than dry studies.

Wim Wenders, Alice in Instant Wonderland, (1973), C-print, 8.5 x 10.8 cm. Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

Looking at them is like experiencing the world through the lenses of the artist himself. The polaroids introduced by Blain|Southern genuinely tell a story, and this is the story of Wenders in the first person. There is a small snapshot, some slices of tomato out of focus, a pile of what looks like cottage cheese with a red, candied cherry on top. The photo was shot while filming Alice in The Cities. Yet, it does not talk about Wenders’ experience as a film director but, rather, it refers to its immediate everydayness. The artist recalled how, on that day, he had just been given the prototype of a new Polaroid camera. He was so excited that he immediately started using it in amazement, taking a picture of the first thing that caught his eyes: his breakfast.

Wim Wenders, NY breakfast, (1973) C-print, 8.5 x 10.8 cm, Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

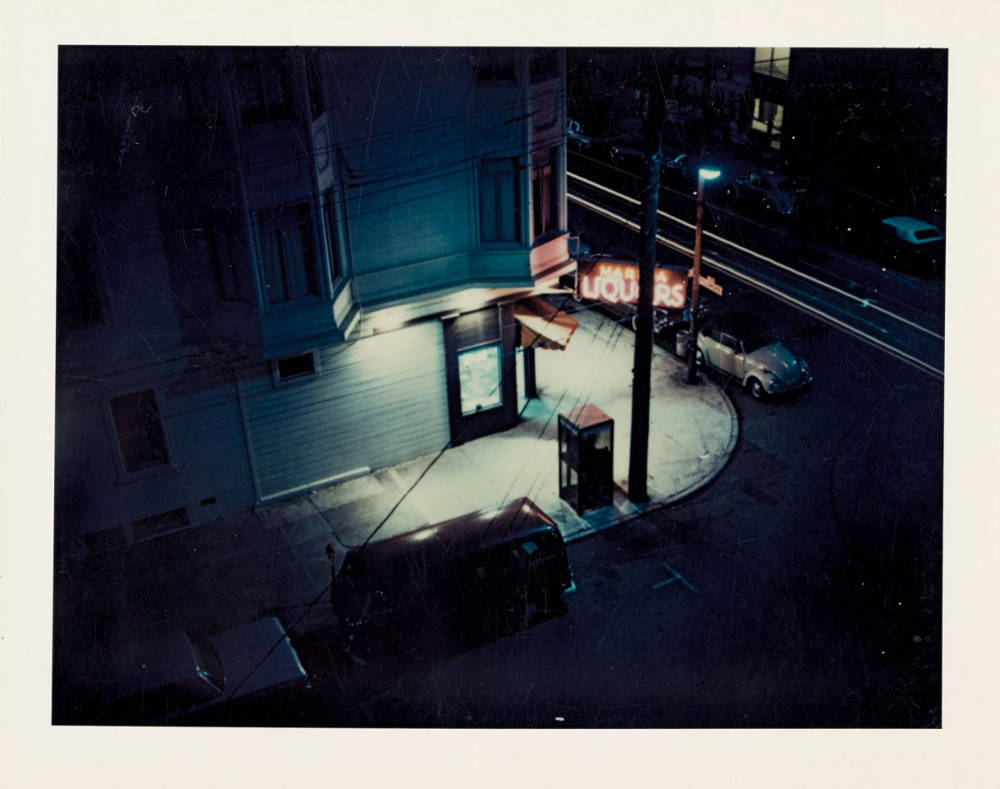

Nevertheless, at the same time, these pictures recount the story of all of us. Walking through the space of the gallery transports you into a parallel state of being, and you imagine yourself living the same experience of the photographer. One moment you are standing in front of a brasserie in Paris, and, a second after, you are wondering around the deserted cities of Texas. Take another step, and you will be catapulted in a Hopperian scene, looking in solitude at a desolate liquor shop in the streets of San Francisco.

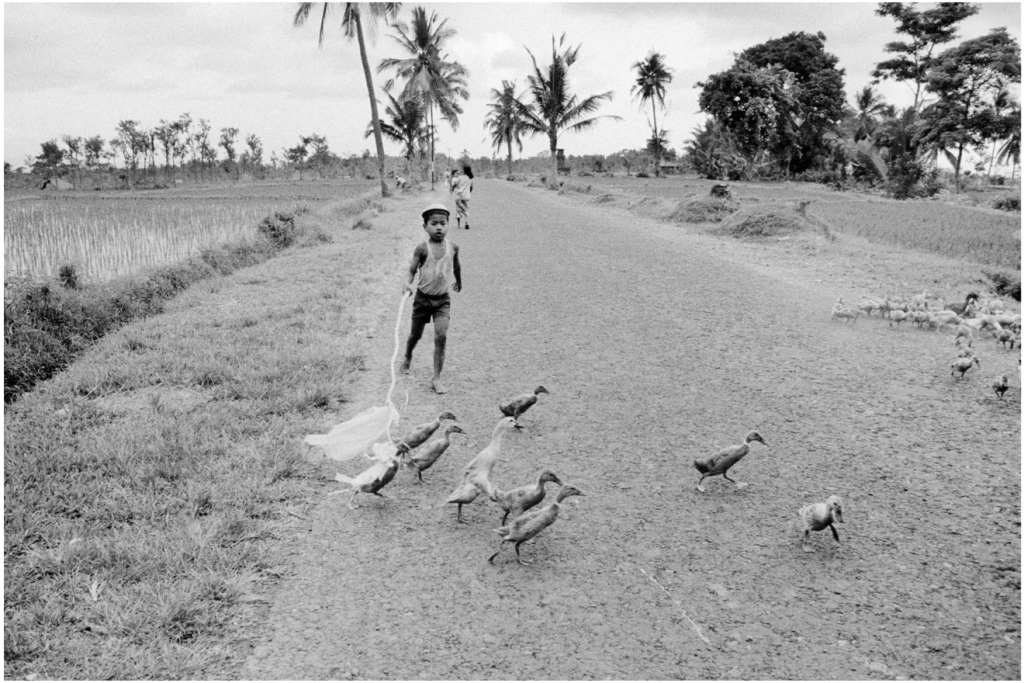

Wim Wenders, Boy with ducks, Bali, 1978, Silver gelatin on Baryt paper framed behind glass on Alu Dibond 40 x 60 cm, Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

Wim Wenders, Waterfall, Iceland, 1973, C-print, 8.5 x 10.8 cm, Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

The universal character of this narrative is enhanced by the great absence of people in the images. Only a few, in truth, have as protagonists familiar faces. This exclusion of humanity did not occur by chance. As a matter of fact, Wenders believed that the introduction of people in a depiction would have immediately conquered all of the attention and curiosity of the spectator. But as this instantaneous shots were intended to narrate the life journey of Wenders, they could not have allowed for the intrusion of monopolizing stars.

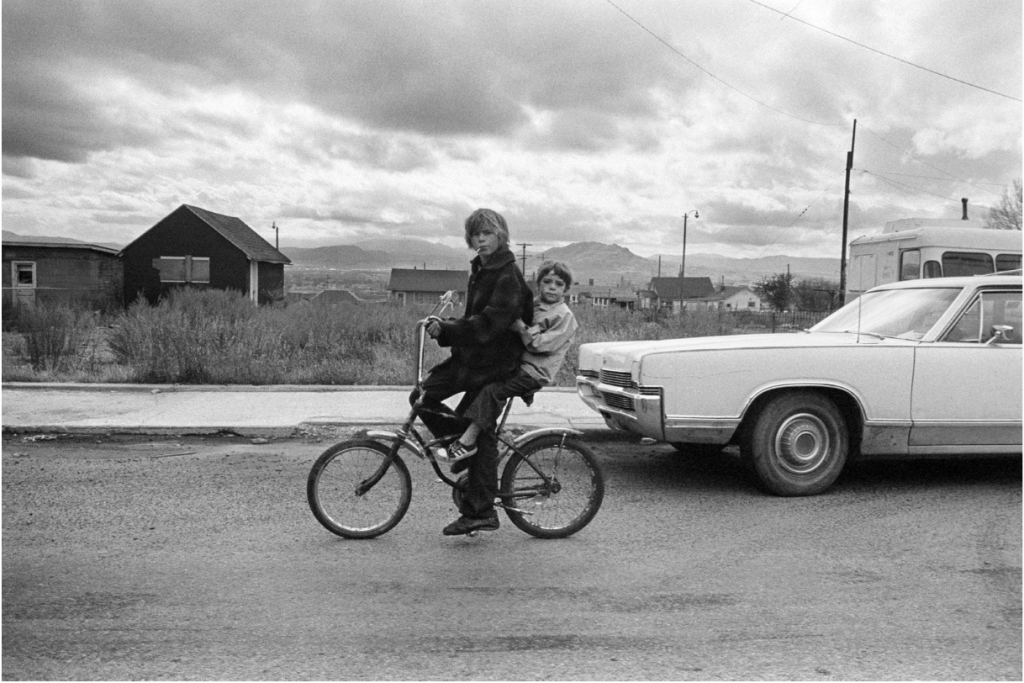

When people are there, though, they are there for a reason. Kids in Butte, Montana depicts a (12 years old?) chap, with a sigarette in his mouth (still hoping it’s a lollipop) with his brother, probably. They are in Butte, the city of Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest, a significant book for Wenders. The two boys are on a bike, looking fiercely at the spectator, but somehow nostalgically as well. Around them is just desolation.

Wim Wenders, Kids in Butte, Montana, 1978, Silver gelatin on Baryt paper framed behind glass on Alu Dibond, 40 x 60 cm, Courtesy Blain|Southern, © Wim Wenders

As I have already stated, the artists was very much concerned with the organicity and uncontaminated truth of the stories he was to delineate through his polaroids. Although no technology infringed the surface of the polaroids, and only time, casual light and chance played a role in the eventual alteration of their facades, the C-prints presented in the gallery have, in some occasion, been enlarged. It might be worth asking whether this change in scale couldn’t itself be considered an artificial alteration. Size is not, usually, the first thing we worry about when analysing an artwork. This doesn’t render it less important. The physical scale of something is what, ultimately, decides the category an artwork could fit in. As Robert Morris remarked, “beyond a certain size the object can overwhelm and the gigantic scale becomes the loaded term”. Polaroids are naturally about the size of an adult hand, and therefore have a very haptic appeal, an extraordinary intimacy and tactile feel. When their proportions becomes something like ten times bigger than their original, this visceral affection is inevitably transformed into something more spectacular, public, formal.

Wim Wenders Early Works: 1964 — 1984 to 5th May 2018 Blain|Southern London www.blainsouthern.com