Tate Modern’s Giacometti retrospective (to Sept 10) is the best chance to see the sculptor as more than an existentialist. Yes, there are plenty of etiolated figures and murkily tentative portraits in his mature post-war style, all great in their way. Giacometti’s lively and also-famous surrealist phase – from 1931 to his ior to his excusion rom the group in 1935 – is well-represented, too, But you might in addition consider:

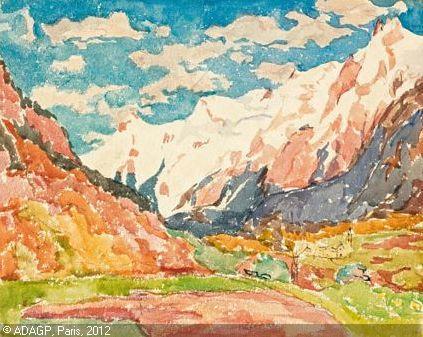

Giacometti the Fauve: actually Tate misses a trick by including none of Alberto’s very early landscapes, clearly inspired by the similar work of his father Giovanni, an established painter in that style. This church in Borgonvolo is from 1920.

Giacometti the Cubist: among various works with a cubist influence, filtered through a life-long reverence for Cezanne, is his paradoxically twelve-sided ‘Cube’, which may refer to throwing two dice.

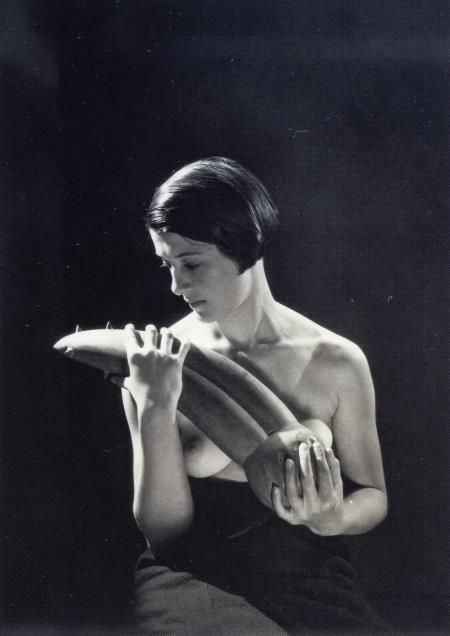

Giacometti the Obsessive: ‘Disagreeable Object’ has primitivist, surrealist and fetishistic qualities – and has been seen as a metaphor for frustrated desire, given Giacometti’s somewhat troubled sexuality: he’s said to have been pretty much impotent other than with prostitutes. Man Ray’s photograph shows Lili complicating that narrative by holding the sculpture as if it were a baby.

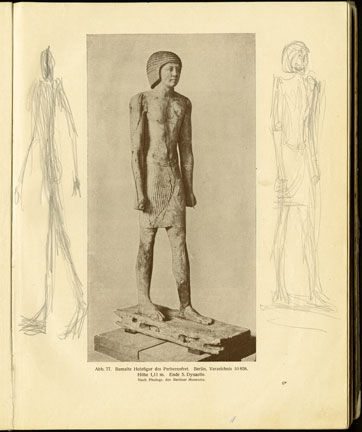

Giacometti the Egyptologist: Giacometti considered Egyptian art an unequalled pinnacle, and one highlight is his copy of the book ‘History of the Ancient Egyptian Civilisation’, on which he copied across various illustrations in exploratory-come-tribute mode.

Giacometti the Minimalist: There are five ‘gazing heads’ at the Tate, flattened forms in which indentations suggest that features have been removed, giving them a hauntingly elegant presence.

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?