London is a city with a rapidly changing skyline. The Brutalist estates and tower blocks – and the communities that once inhabited them – are being demolished, displaced and in extreme cases killed to make way for ‘redevelopment’. These unique concrete monoliths that soar towards the skies are being replaced with low-rise, characterless homes for the wealthy, while vast numbers of people are being exiled to the suburbs away from their friends, families, jobs and the communities that raised them.

These so-called eye sores that are either torn down, sold off privately by councils or covered in flammable cladding – so as not to offend the sensitive gaze of the upper and middle classes – have long been ignored by society at large, but recent events have brought them into sharp focus.

The Grenfell Tower fire in June highlighted the neglect and poor treatment of communities by authorities whose only concern seems to be to cut budgets, cover their tracks and continue to line their pockets and those of foreign investors.

Estate Agents is a collaborative project between artists Andrew Gillman, Maeva Berthelot and Ivan Bliminse, which celebrates the rich histories and stories these spaces hold, whilst also documenting the crisis they face. Over the last three years the trio have been exploring and chronicling these dilapidated buildings in an attempt to capture the beauty and complex infrastructures that have existed inside them for decades. From illegal drinking dens to pirate radio stations, these buildings have been home to an integral part of the cultural landscape of London – something that is quickly being jeopardised.

Using three very different but complementary styles of photography the group has amassed a body of work that digs right to the heart of the estates, also giving insight into their explorative process and the unique moments they have been so fortunate to have experienced.

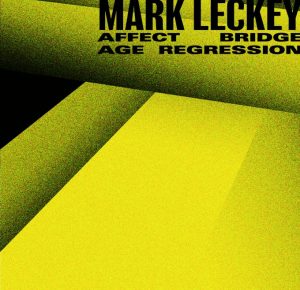

I caught up with them while they were preparing for their upcoming exhibition – Estate Agents – which is taking place in the carparks under the Ledbury Estate in South East London.

Who are you and what do you do?

MB: I’m an artist from Paris, from I suppose the equivalent of Lewisham. I was born and raised in a tower block and think this is why I feel so at home in the heights.

I’ve been working mostly with movement over the last few years, but developed an interest and a passion for photography. I’ve been working in a medium that gives you nothing physical to hold. With performance, once you perform it’s done, it’s gone.

I’ve been on the road for the last 15 years working, traveling, performing and always had a camera. This was my way of keeping a trace or memory of what I had experienced: the places, the people. Now I’ve landed in London and I’m not working so much with performance it gives me the opportunity to reflect on the content I’ve gathered over the years – to utilise it and really think about it and build more material out of it.

IB: I’m a Londoner born and raised. I suppose this project just stemmed from exploring. I’ve been exploring since I was a kid, it’s just now that it’s become more important.

I guess me and Andy knew each other from our previous lives. We bumped into each other a few years ago – actually the first time Andy was out painting after he’d just got out of prison – and I was just starting a photography degree. We always had common interests and we just started exploring the Heygate. We went there three or four times and through that started to gain access to similar blocks. We had links to people in pirate radio who helped us gain access.

AG: I’m from a funeral directing background – It was the family business and it’s what I did after college and uni for quite a long time. Since around 2010 I’ve been freelance. I’m from a graffiti background creatively, I guess, and I’ve always taken pictures through that, in a documentary style, to serve the purpose of documenting the piece before it disappears.

The last few years I’ve just been working out what I really enjoy creatively, whether it be painting, photography, filmmaking. This project again ties in with my need to document things before they go, disappear. You know, before times change.

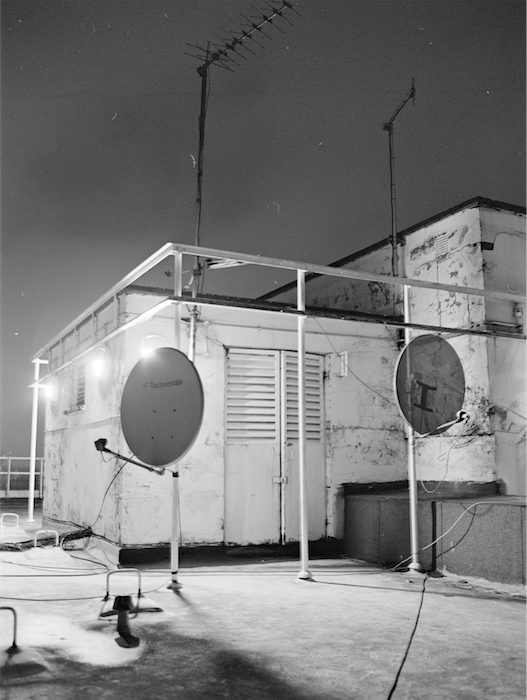

The background of funeral directing is a traditional London thing and I have strong interests in other London pastimes or sub-cultures. I shot a short film about the banger racing at Wimbledon – which is now closed – and made another short about a guy that does bottle digging. This project is influenced by pirate radio and how that it’s a bit of a dying art but has played such a huge role in the London music scene. Finding a lot of the relics from old pirate radio stations in the blocks is really cool.

I’ve always explored, jumping into these places to take photographs, from estates to warehouses, and squats to graffiti places. It sort of comes natural and it’s something I’ve done from a young age; this project has just been a natural progression.

How did the show come about?

AG: The Heygate in Elephant and Castle was the starting point. We were there in 2013 and the real draw was that it was this no-mans-land in the middle of London. I mean, there was no one there apart from a handful of residents. We would walk around and revisit and I think on the third visit the roof was finally open.

Then we also found the Haggerston estate off the Kingsland Road and another in Mile End. This began our documentation of these buildings and communities that were soon to be demolished, and we just wanted to do more.

I had just been a ‘point and shoot’ guy and Ivan’s approach – who had just come out of photography school – was interesting for me because I didn’t really know anything about photography. We all have different styles. I’ve more recently moved into digital, Maeva uses a lot of old SLR and has more of a feeling about the settings and stuff like that. Ivan works completely in film and now medium format – black and white.

MB: We started really spontaneously, but out of curiosity and playfulness it became a repetitive ritual. We would meet up and slowly it developed a deeper meaning – a stronger project that started to naturally build.

We started to realise that there is a real social dimension to the blocks and it’s almost supernatural, which shaped the bigger picture of what we were doing.

With the events at Grenfell being still extremely current and raw, is it important for you as artists to highlight these issues?

AG: There were big scandals around places like the Heygate with residents being issued compulsory purchase orders by the council, and whole communities being displaced and being moved out to places like Eltham. Residents weren’t given the market value of their properties – they were moved away from their families, their jobs…displaced, ripped off and sold out by the council.

MB: Sold out to foreign investors.

AG: So now these places will just become luxury apartments. We see what is now where the Heygate was, and we see what’s in Battersea Power Station, and know these places have a minimum quota of social housing. The model has changed. In post-war Britain the Brutalist style of social housing – this sort of utopian vision – is no longer considered to be cool. What people now see as an eyesore we saw beauty in even with the decay.

MB: The colours, the textures, the patterns, the lines, the staircases! We really got into it, you know?

AG: We started looking at other Brutalist estates. We went to Robin Hood Gardens, then a year later there was a compulsory purchase order – everyone is kicked out. It’s not a listed building. They listed the Balfron Tower but didn’t list Robin Hood Gardens, which seems like a crime – they’re gonna demolish it.

What’s happened with Grenfell has brought out the true colours of councils in London – they don’t care and they don’t invest. I mean, a lot of what we find interesting about the buildings is the neglect and how they managed to get this way. They’re not doing the fire regulations, everything is broken, and there’s piss in the lift.

MB: The estate where we are doing the exhibition, the residents are only now being listened to in the light of what happened at Grenfell. Before that it didn’t seem to matter.

The government are like children scared of being caught rather than caring. It is so obvious now that they have to do something.

Coming from a creative angle that isn’t always necessarily legal, how does this inform your practice?

AG: As an artist now it’s important to show my work, but I’m from a background where you hide your pictures – you know, where you’re really staunch – you don’t tell anybody anything. Who you’re moving with, where you’ve been. That’s cool and I have a huge body of work from that part of my life, but this is different. It’s about showing people what we have found and what we’ve documented. It’s all done in a respectful way and it’s important; I’m proud of that and and I want it to be seen.

The whole process of doing this show has been fantastic: working together to a deadline and then showing what you’ve done is a huge journey, and it’s important to do that so we can move on to something new.

IB: We live in an age where nothing lasts long and photography lasts for a matter of hours. There’s a lack of nostalgia in a lot of photography. It would be interesting to have this body of work available in 20 years time when the subjects have disappeared. I feel like there is still so much to do and it’s so quickly disappearing.

AG: But that’s the great thing about London: it’s all on our doorstep. We don’t have to go to far, we’re not segregated like other cities. And there is always more to discover. You know you can be on the top of one tower block and see three more and think: “Bang – that one next.”

IB: Getting our bearings on a rooftop, trying to work out where these other places are, then setting off to find them.

Graffiti is a lifestyle and it teaches you a lot, but we’re now visiting these places with a completely different intent. You learn to appreciate them as something special that not everyone gets to see. We use a similar practice with a more mature approach to capture these experiences.

AG: You have those magic moments with graff where you could be walking down the [train] tracks at 4am and it’s just you and a fox, and it’s a full moon and you’re in complete silence. You can smell the pollen on the trees and it’s like this is magic. We have those moments with this: we were on a rooftop at 4am and a seagull just saw us and started circling and hung out for half an hour while we did our thing. These are things most people don’t experience.

I’m a bit of a magpie. Part of the whole experience is some of the treasure you find: the artefacts. We’ve found a lot of stuff from old pirate radio stations in forgotten parts of the blocks that the council can’t be bothered with. The signs of life and the history of people wanting to put up a rig and play music to people for free – it feels very unique to London.

MB: Growing up in a city when you are on the top of a block and it’s still it’s like being on top of mountain; it’s a universal feeling. Anyone on a rooftop could connect to the feeling of freedom.

AG: London is becoming a millionaire’s playground: the poor are being pushed out to the suburbs, people can’t afford to be here. A place that used to be so mixed is rapidly changing.

With something like Grenfell all the communities pulled together to raise millions and really help each other, and now these communities are being torn apart to accommodate the wealthy.

Estate Agents opens this Thursday the the 13th of July in The Ledbury Estate, Old Kent Road SE15 1QP and runs until the 16th. There is an accompanying zine with the exhibitions with all proceeds going to the victims of Grenfell Tower.