FAD sat down with artist, Elliot Dodd to discuss his practice and his current show with Zabludowicz Collection Invites. Dodd is showing The Manbody, a 4K digital film that borrows its stylistic structure from Hip Hop music and commercial promotional videos. The show runs until 28th May, with an artist’s presentation event on Sunday 21st May, 3pm.

Elliot Dodd, The Manbody, 2017, 4K digital film.

The Manbody is a continuation of your use of avatar characters placed over filmed footage, creating a bizarre and uneasy atmosphere for the viewer. How did these characters come about and what is their importance to the work?

I started using them after watching Marianne Trench’s Cyberpunk, a documentary made in the early 90s about cyberpunks and computer hackers. The way they’d used early, clunky computer graphics to mask people’s identities stuck with me. The animation blurred and masked their identity in a way that changed them but you still felt their presence. These digital identities act as ciphers to deliver the film’s dialogue and standpoint.

Was it important that these masks were digitised?

Yeah. I wanted to create a mesh between digital animation and film footage. I used tracking on the character’s faces to create the avatars so it’s almost embedded into the person. You get a really accurate, uncanny movement of something really fake on top of something very real. I like that you read the animation as something digitised but you’re forced to buy into a direct link to this real life character by its movement.

It’s interesting that you mention the ability to hide parts of people’s identity through these avatars. Your work is often concerned with how masculinity functions in society as well as for individuals. Do you see these traditional markers of masculinity as a form of hiding?

I think I’m really baffled by other people and I guess particularly men in the way they conform to certain things. I have a strong sense of how pervasive and negative a force that has been in the world. So it’s a frustration and bafflement with the continuation of this system. I guess in some ways, the film functions as a way to emulate a specific mode of communication (that of a rap video or advertisement) which is constructed and performative. With the avatars, the relationship to identity is about being able to perform or converse through something non-human.

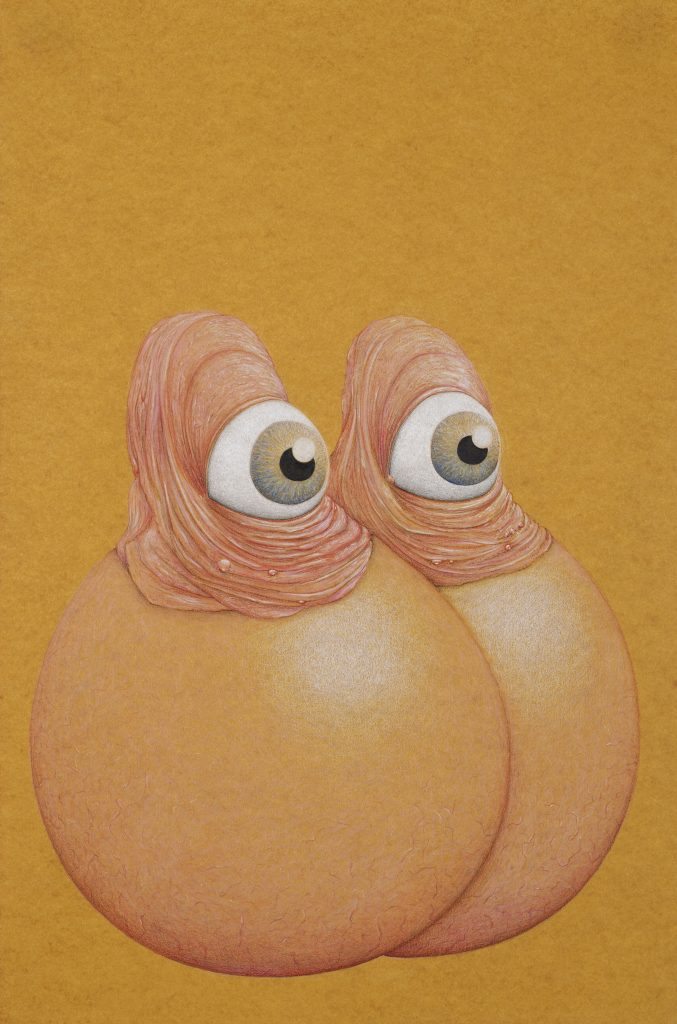

Elliot Dodd, Yeezy Boost Balls, 2015. Coloured pencil and ink on card. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph: Andy Keate

You were saying the text (which uses Plato’s Timaeus as the starting point) is very cyclic and I guess it’s a type of performance in itself.

The text comes from a dialogue and speech essentially constructing the whole world at different scales from complete creation back to cell biology, physics and chemistry and interlinking that into really base level notions of gender and hierarchy. In Plato’s text, (of course) the male is a the top, then women, then ducks, then fish etc. Things that move nearer the land (reptiles etc) are more stupid because they’re closer to base level: soil, earth, rock.

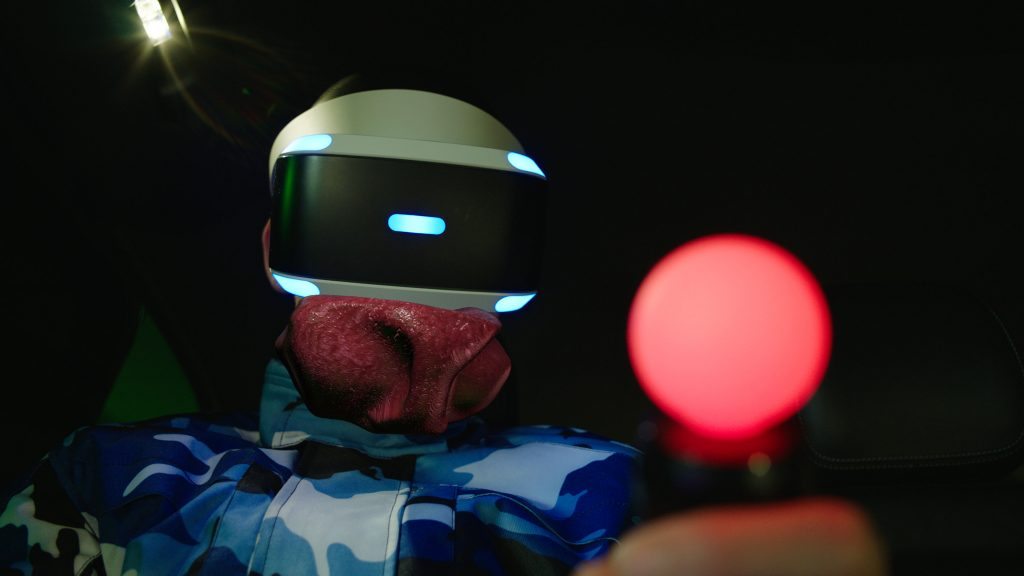

What is your interest in the relationship between the body and VR?

I’m really interested in the limitation of your functionality when using VR like being able to see or hear whilst you’re inside it. I like the idea of that becoming more commonplace – a normalisation of that activity that can now happen in people’s houses or on the bus. You can be in your own world and have no cognition of the outside world. I find that exciting and apocalyptic at the same time.

Elliot Dodd, The Manbody, 2017, 4K digital film.

Elliot Dodd, The Manbody, 2017, 4K digital film.

What drew you to such an old text when dealing with contemporary culture?

I didn’t think about the fact that it was old. That wasn’t what I was drawn to. I was reading Bataille at the time I got into it. It sat happily alongside that as a weird mode of investigating the world. There is a certain excitement when you think about how old it is but I don’t think that was a drive. I was attracted to the dynamism of the text and I knew I wanted to use it for a new conversational film. The friend that introduced me to it is a writer so I had an instinct to set that up as a collaboration and create the script together. He’d go away and write up a really clunky, mock up dialogue, then we’d take it apart and restructure it. It was a kind of working through and filtering process.

Is that why it doesn’t come across in a linear way and as you were saying, has parts that feed into each other and loop back?

It does to a certain extent. There’s a degree of nonsense to it, almost like a cut up poem. But ultimately, it needed to hold together as Character A and Character B. So it goes between elusive and clear.

What were the reasons behind choosing male American voices?

It seemed like it would be cohesive in terms of it being a kind of hip hop music video. The voices in my previous film are English and purposefully jarring whereas with this one, I wanted to have a blandness. Everything seems sophisticated and it’s almost quite bland in the same way music videos drift along at a similar tone and speed.

The fact that there’s a female character voiced by a man is to enforce the unreality of the situation that nothing quite sits together. The female character is dealing with the ‘geometry’ of the text whereas the male character deals with the froth and phlegm of the body.

Although the film has a very strong visual language, there seems to be an irony to it. The shiny car shot as if in a slick advertisement is incongruously parked in a low ceiling, claustrophobic carpark. Can you talk a bit about this?

I actually chose the carpark because I thought it was really slick and high-end and very clean and it felt like a TV studio. It wasn’t dingy or sordid. It felt like an equal object to the shininess of the car. So it wasn’t chosen with that irony in mind. It ended up in the film coming across more claustrophobic and cramped. However, I was also looking to present a series of containers: a static space with a static car with static people with a static text.

It’s failing to be something deliberately. We used the modes of music video production so the camera isn’t still at any point. I was trying to get the energy only present in those types of videos so you have this floating, fluid impossible camera movement the whole time.

But this does feel in contrast to the stilted way the characters are sitting for example. There’s a distortion of the hip hop video formula.

It is doing that but it’s all done with love. It’s coming from a place I really like so I’m not seeking to destroy it. It’s trying to inhabit something. I’ve been fascinated by this camera work for a while so I wanted to force it together with my own interests and methodologies and see what came out at the end.

Can you tell us about the costumes in the film?

I followed a process with a fashion photographer to curate the outfits. We discussed the character traits going through the dialogue. The contrast was important, as well as what they contained in themselves. There’s an organic element to the female character’s dress (made of fake hair) and the other costume is very rigid (a motorbike outfit with geometric camouflage). The VR headset was also a choice. A defining element to his ‘look’ was the headset. I wanted it to be a full-body look. As well as these aesthetic choices, I was interested in using a fashion photographer because of his very direct route in terms of being a professional in the industry.

Elliot Dodd, The Manbody, 2017, 4K digital film

Elliot Dodd, The Manbody, 2017, 4K digital film

This professionalism seems important to the video.

Yeah, I was working with lots of people I respected. They’re working in a high level in their industries. There was an element of getting a job done in a more direct and professional way than an ‘ephemeral’, artistic route.

It’s interesting that the production of the artwork actually worked in the same way as a genuine hip hop video.

That was the key thing. It had the feeling of a proper shoot – a lighting guy, a camera person, someone doing the tracking shots, hair and make up. That’s the case in all the work I do. I need to sort of blind myself from it being art and instead feel like I’m drawing a diagram or logo or inventing a new product.

To distance yourself from it being an art object?

Well, I do want it to be viewed in a gallery context. I think that’s a really efficient and interesting way to look and analyse things. But in the making of it, I can get more excited about it if I feel I’m inhabiting a different, defined world. In this case, that was music video production.

Elliot Dodd (B. 1978 Jersey, Channel Islands) lives and works in London. He studied at the Royal Academy Schools, London 2013–16. Previously he completed his BA at The Slade School of Fine Art, UCL London 1998-2002. Recent exhibitions include: Virtually Real, collaboration with HTC, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2017; Semi Self Reflections, Rockelmann &, Berlin, 2017; SUNDAY Art Fair solo presentation, London, 2016; Event Horizon, Gabriel Rolt Gallery, Amsterdam, 2014; Switch, Baltic, Gateshead, 2012; Pluscom, Milton Keynes Gallery, 2013; Ear Found, Ana Cristea Gallery, New York, 2012.

Zabludowicz Collection Invites: Elliot Dodd until 28th May

Zabludowicz Collection 176 Prince of Wales Road, London NW3 3PT. www.zabludowiczcollection.com