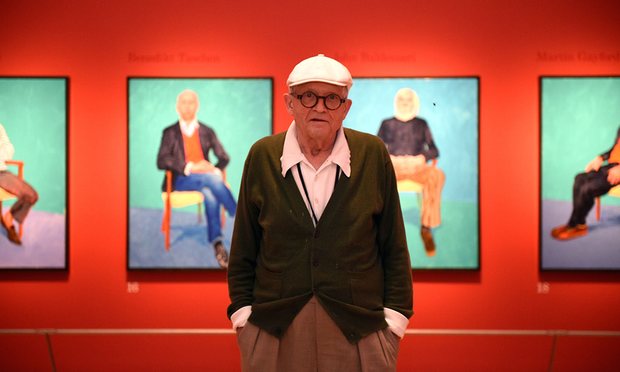

‘Letting loose Hockney’s raw instinct for colour’: David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life. Photograph: Andrew Matthews/PA

![]() This article titled “David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life review – ‘We can feel Hockney’s deafness'” was written by Jonathan Jones, for The Guardian on Monday 27th June 2016 21.00 UTC

This article titled “David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life review – ‘We can feel Hockney’s deafness'” was written by Jonathan Jones, for The Guardian on Monday 27th June 2016 21.00 UTC

David Hockney is a relentlessly experimental artist, in the original sense of the word experiment, which means the testing of truth against experience. The artist is interested in how we see and how we can adequately record the evidence of our eyes. His restless quest for visual truth has led him from cubist photomontages to plein-air paintings – and now to an intriguing exploration of the nature of portraiture, in which 82 different people all pose in the same elegant chair, perching, sprawling or slumping themselves on its lemon upholstery, faces ruddy or pale, accepting the scrutiny of his pencil and paintbrush.

What is it, in the 21st century, to have your portrait painted? It is for one thing a gloriously archaic exercise, a few hours of escape from the speed of modern life. Just do it, says the slogan on Avner Chaim’s green T-shirt, under his striped purple zip-up jacket, yet he’s been taken out of the rush of the big city, sat in Hockney’s old-fashioned chair, and must wait for the artist to do his work.

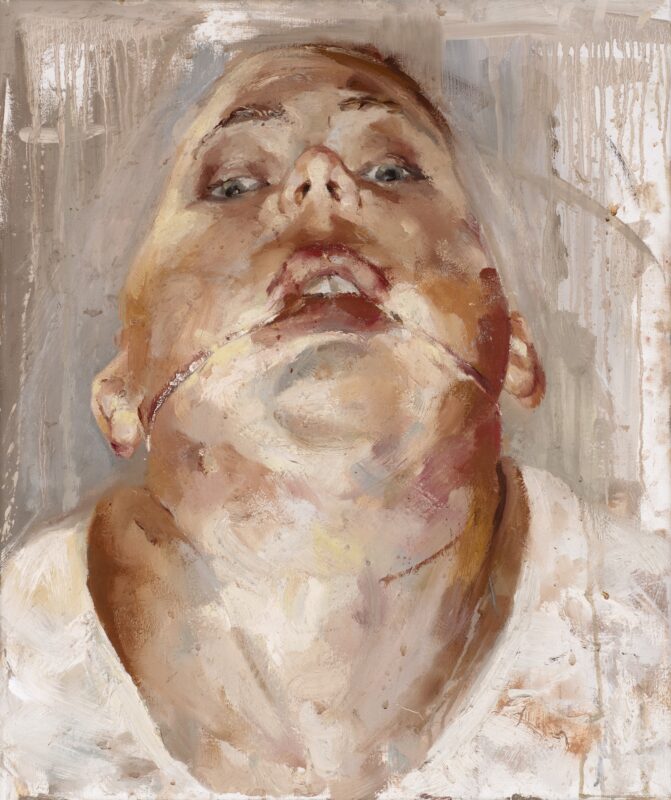

Lined up in the Royal Academy’s Sackler wing, these paintings add up to a single work of art. Hockney is no Lucian Freud, aggressively peering into the fleshy secrets of human frailty. He is a much kinder artist. As studies of individuals, these are relaxed, humorous, mildly quirky painterly snapshots. And yet, of course, they are not snapshots – they are paintings, and that is the point.

Hockney has, since the 1960s, not only made art but thought about it, spoken about it, written about it. He has a book about the “history of pictures” coming out later this year, following on from Secret Knowledge, his provocative book claiming that painters experimented with cameras as early as the Renaissance. His practical and theoretical meditations on picture-making return again and again to the similarities, differences and hidden connections between photography and painting. Yet in this exhibition, he seems to be saying that when you have your portrait painted it is not at all like having your photo taken. It is not a record of you: it is an artefact, a beautiful thing, a dance of colours.

These are chromatically superheated pictures. Clothes make the person, for Hockney dwells on vibrantly perfect little details: a dabbed pool of silver creates a watch, a flourish of whiteness concocts flamboyant shoelaces, rucks of shadow nearly suggest the shapes of skirts and shirts. The deep blue and green of the studio setting sets off all these casual everyday displays of colour – nothing exotic, just the clothes his sitters happen to be wearing. And yet it is a dreamy pageant of pattern and fashion, from stripy matelot tops worn by friends who evidently know what Hockney likes to paint, to necklaces glistening like stars.

The artifice of the exercise is revealed by a comical clue: everyone is a little bit smaller than life. They have been removed by that diminution from the real world, into a world of art. In this painted place, a phone in a pink shirt pocket is suddenly a mysterious patch of darkness against brightness.

This entire exhibition is a homage to Henri Matisse. It lets loose Hockney’s raw instinct for colour. Caught in his museum of modern colours, his sitters smile or sulk, spread their legs, or fold their hands. In the first of the series, JP Gonçalves de Lima buries his head in his hands while his feet are planted on a Matisse rug of ecstatic zigzags. In another picture, Chloe McHugh hides behind a face as opaque as a fauve mask. What are they thinking?

Perhaps in the distance and silence of these portraits, we feel Hockney’s deafness, which he has said inhibits him socially. Or perhaps we feel the mystery of art itself, which echoes the world and yet transfigures it. Amid all the portraits glows a single gorgeous still life. The objects in this lovely little painting are given form and solidity by colour alone. Colour can create shape, weight, volume and texture – it can make the world more real, more alive.

Hockney still thinks Matisse and Picasso are the gods of art. He is right, of course, and this exhibition, which will be seen by some people as lamentably “conservative”, actually distils a little bit of modern art’s true fire. Another fascinating experiment by Hockney.

- At the Royal Academy, London, 2 July to 2 October. Box office: 020-7300 8090.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.