Gilbert & George pose outside their home with one of The Banners posters

If you think about it, you’ll realise you’ve had a funny feeling too. London has felt incomplete, bereft as if part of the furniture is missing but you cannot quite put your finger on what it is or where it has gone.

The problem has been that we have not had an exhibition by our favourite Londoners for just over a year. A whole year. Without it, how could we possibly know the state of play in the backstreets of Spitalfields or whether Liverpool Street is still the centre of the universe or how many plane trees there are on the Charing Cross Road? Now the wait is over, as Gilbert & George return to White Cube Bermondsey for a third time with a new series of works.

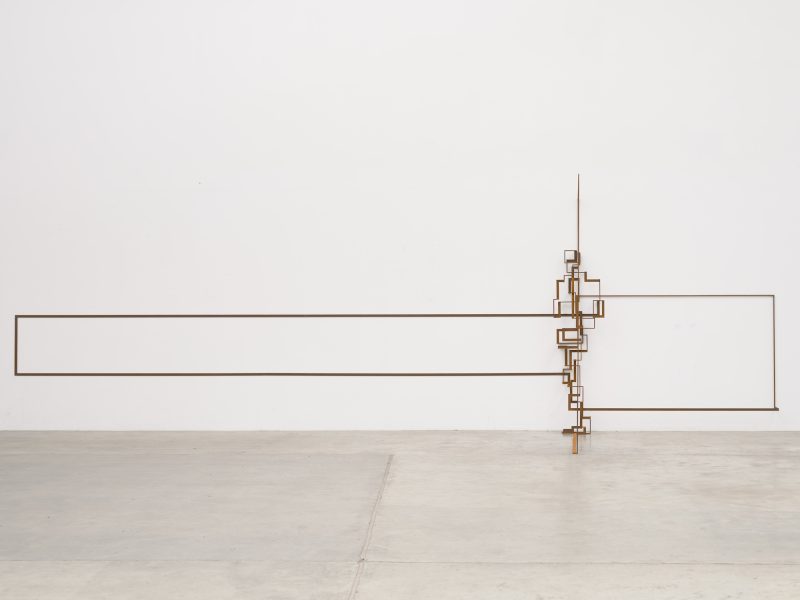

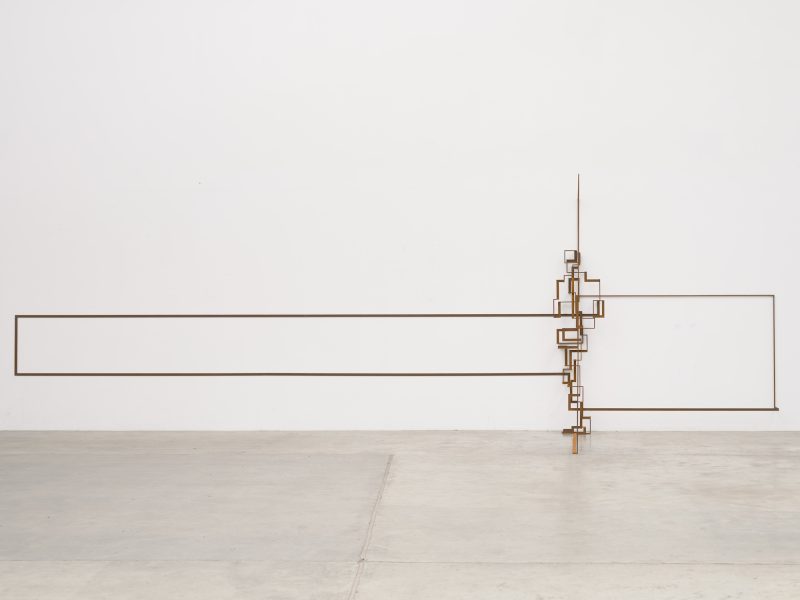

Every so often Gilbert & George, the British artworld’s aristocracy, will exercise their right to change direction, as they did in 2011 when they reverted back to making postcard sculptures for the first time in 20 years. This time they are appropriating the aesthetic of street art, making text-based works with no sign of a dick, a bumhole or even the artists themselves. There aren’t even any rough East End boys. Sorry, lads, this is a serious exhibition. The Banners marks a departure from their usual grid-format pictures, but closer inspection reveals it to be the continuation of a life’s work.

In these new works, Gilbert & George present slogans that crystallise the anti-establishment message they have been promoting throughout their career. It’s a kind of philosophy, although they dismiss academic philosophy as inapplicable to life, and Gilbert & George are all about life in its immediacy, brutality and pleasures. In the same way as ‘Underneath the Arches’ expressed their longing, determination and contentment when they were baby artists, The Banners express a way of living which eschews bigotry and any brand of conservativism that denies the pleasures of the flesh.

Here is one of the beguiling paradoxes of Gilbert & George: while they claim to be passionate monarchists and Tories, they also espouse an uncompromising liberalism, as if the uneasy children of John Stuart Mill and Margaret Thatcher. A picture of David Cameron hangs on the wall of their studio at Fournier Street as they tell you they refuse to sign a petition to ban drinking on the streets of Brick Lane because they’d never do anything to stop young people having fun, even if some people call it ‘anti-social behaviour’. And there is no sense at all – not a smirk nor a careless whisper – that they are peddling a contradictory blend of Conservatism and Liberalism for effect. It seems, as everything in the world of Gilbert & George does, flawlessly genuine, even if it is probably manufactured. The craftsmanship of these little inflections and nuances of character is so refined, engineered for durability and efficiency. Although the politics may have been an affectation they concocted as part of the act in the 60s, it is so well-crafted and well-honed that it seems utterly sincere, logical and necessary, as if, given time, they came to believe everything they ever said.

There are thirty Banners in total, consisting of three iterations of ten distinct messages, each beginning with “Gilbert & George say :-”. Their iconic signature, which adorns every picture as well as every book and poster they have ever produced, is written in the artists’ hand in vibrant red paint on the largest available size of watercolour paper. Then comes the assertion in black spray paint, continuing the red/black/white colour scheme of their recent pictures: Gilbert & George command “Fuck the teachers”, “Felatio for all”, “Fuck Him”, “Decriminalise sex” and “Ban religion”. The most outrageous of all, in sublime Gilbert & George style, is “God save the Queen”, which gains its power from the fact that it is the only one that most people would disagree with.

As students at St Martin’s Gilbert & George were appalled by the artworld’s rejection of colour and emotion, so they injected both into their art. They were also sceptical about the orthodox view of sculpture as consisting of an object of a plinth, so they made themselves living sculptures, performing as The Singing Sculpture and making vast charcoal drawings of themselves wandering around Hampstead Heath. In their pictures, they depicted the degenerate, down-trodden low-lifes of Spitalfields, which in the 60s and 70s was little more than a slum. They made photographic sculptures of themselves drinking and having a debauched time in the pubs of Bethnal Green. During the 1980s the pictures focused on boys, such as David Robilliard and Martin Clunes, affectionately photographed in their Fournier Street studio, made to look beautiful and yet always interpreted by critics as exploitative or threatening. Indeed, from East End tearaways to Bangladeshi immigrants to fledgling models, Gilbert & George’s boys stand out in the history of art as the only depictions of masculinity that are simultaneously arousing and loving. And then there are the pictures of shit, piss, spit and spunk: piss flowers, piss steams, eight shits, shits and bums, naked shitty world, spunk on sweat, spunk on piss, and spunk money.

Gilbert & George have always been about challenging the orthodoxy, showing in their pictures the things that are rejected or ignored by polite society. The Banners just extend this to a series of commands that they, in good faith, think will improve society if adhered to. After all, the abiding logic of the Naked Shit Pictures was that we all have bumholes and we all shit so it won’t do us the slightest harm to be open about it and to see it for natural, harmless fact it is. The Banners are moral exhortations that go against the grain, or at least express what we are all thinking but dare not say publically. There has always been that strong moral sense in Gilbert & George which simultaneously fights bigotry and offers an alternative in the form of equally dogmatic commands to challenge the established order.

These new works have their origins in two sources: first, in the Scapegoating Pictures displayed at White Cube in 2014, there was a triptych which featured slogans such as “Padre is a poof” and “Cuddle a cadet”; second, the Dirty Words Pictures of 1977 which showed graffiti on the streets of recession-stricken London, unveiling the grit and discontent of the Capital to a world that thought London to be the pinnacle of civilisation. In all their previous work, and now in The Banners, Gilbert & George are overstepping the mark of politeness because art, if it is to speak direct to the people, cannot afford the mores of polite society or the complications of art-speak. This is the simple and sometimes brutal honesty of Gilbert & George at its most direct, the purest expression of their rejection of the established order and the affirmation of ‘art for all’.

Words: Daniel Barnes

‘Gilbert & George: The Banners’ is at White Cube Bermondsey until 24 January 2016.