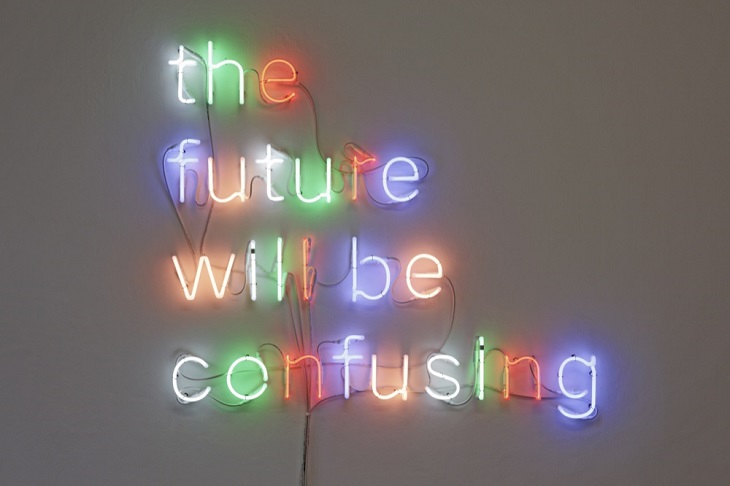

Tim Etchells, ‘the future will be confusing’, neon, 2015

August is a quiet time in the artworld. Galleries have summer shows that drag on, nothing new opens and everyone who can afford to take a month off goes on holiday. The rest of us are still here, not exactly slaving away because there’s nothing to slave at, but languishing in the doldrums. Now the first shards of light are starting to creep through as galleries announce their September shows, bringing a ray of hope into a year of bad art.

So far, 2015 has been a pretty grim year for art in London. Most of what I have seen – I mean, 99% of it – has been unadulterated slurry, owing to a dire lack of decent new talent on one side and the complacent lack of imagination from the big hitters. The rules of my profession dictate that I can’t name names of the little guys who’ve failed, and nor would I want to, but it is noteworthy that the big guys – Hauser & Wirth, Gagosian, even the Hayward – have failed to turn in a show that is worth the emulsion on the walls. And now I suspect they’re saving it all up for Frieze.

That is not to say there has been nothing worth seeing. White Cube’s Gunther Forg show was stunning in every dimension, while Lacey Contemporary upped its game with a spectacular Louis Savage show. Richard Stone is unrivalled in his melding of the heroic with the romantic, even when he is not presenting new work, as was the case at James Freeman Gallery. Tim Etchells’ exhibition at Vitrine was an absolute wonder: a confused mass of semiotic conventions burst asunder by a lightness of touch that finds beauty in emptiness. We are still waiting for the Mona Hatoum retrospective to travel to the Tate, but I suspect that might be the highlight of the year.

The thing that these shows had is the very thing that practically everything else is impoverished in: a visceral sense of the value of art as residing in its singular ability to marry the aesthetic and the conceptual with no palpable remainder, where sensation and intellect mesh, meld and unfurl in unison. This is what art should do, the thing that is at its very essence. And, I think, it is at the core of economic value: prices are solely and eternally justified by the fact that they impute monetary value to sensation and intellect, which are in themselves priceless, ineffable values.

Which brings me on to Grayson Perry. I saw his show at Turner Contemporary twice; the first time I loved it, the second time – a week later – I found it hard to see what the fuss was about. In theory, I think Perry typifies the sensation/intellect dichotomy, but in practice I find it lacking. On the one hand, he makes subversively decorative objects that excite the mind to think about culture and class, but on the other hand, all of that falls flat when you confront the awkwardness of the same thing repeated over again. An exhibition that celebrates the career of an artist who, through television and art, has done more to intellectually engage the public with contemporary art than anyone of his generation should have been a riot, but it turned out to be little more than a scuffle.

So I got to thinking that if Perry can’t pull it off, then art is in a bad way. Nobody has quite had the courage to say it yet, but the market is faltering in the face of its own enormity as if someone has rubbed its face in its own vomit and forced it to look in the mirror. Those unsold Richters and Bacons and that very expensive Doig are signs that the tide is turning. This change of tack might explain the bleak efforts of commercial galleries who have finally got the message that bling is so nineties and we need some substance. But, in this transitional period between the boom of the old and the vavavoom of the new, we are stuck with exhibitions that promise the Revelation and deliver a dull thud to the back of the head.

This might all change when the circus comes to town in October. The under-acknowledged virtue of Frieze is that no matter how mad and bad the fair is, its happening makes all the galleries step up their game. The best exhibitions happen during Frieze precisely because, with the world looking on in breathless anticipation, galleries have to put on shows that not only sell but also look convincingly like art. So we have Cerith Wynn Evans at White Cube, William Kentridge at Marian Goodman, Cy Twombly at Gagosian and Liam Gillick at Maureen Paley, not to mention John Hoyland at Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery. These are artists who, at the bare minimum, will simulate the sensation/intellect dichotomy to within an inch of irreality.

And that is, in the final analysis, the problem with a lot of exhibitions of late: they have not even tried to pass as art, but only cynically filled a gap between the white walls because that is what art does. But it should do more. It should invigorate the spirit, enjoin the senses and the intellect and do something that justifies its entanglement with so much money. Or, on a bad day, and we all have bad days, it should at least pretend to be worth a flicker of our precious time before we shuffle off. I think, and if there is any goodness left in the world I do not just speak for myself, the least we can demand of art in the 21st Century is the sensation of art without the boredom of its conveyance.

Words: Daniel Barnes