Auction week got off to a rocky start at Christie’s, with 30 lots sold at or below the low estimate and 13% of lots remaining unsold. It sounds like bad news, but nobody can complain about earning £95.6million in a single night. Nonetheless, a jittery saleroom speaks volumes about the state of the market: lacklustre bidding, stilted by a distinct lack of passion, ensures that the great art bubbles rides the wave right past the usual suspects, even if it shows no sign of bursting.

Among the works that failed to achieve their low estimate was Sigmar Polke’s Moonlit Landscape with Reeds (1969), which realised £3.9million and Christopher Wool’s Mad Cow (1997), coming in at £600,000 below the low estimate of £4million. There is an argument that these are not major works and Christie’s overpriced them, but it could be something altogether more sinister – and more endemic – than that. It could be that the market has been flooded with such works, since every post-war and contemporary art auction features these artists. Perhaps it has reached the point of saturation where everyone who is desperately vying for a Polke has got one, so there is no one left who is willing to break the bank to possess one. If this is the case, then there are dark times ahead: unless seminal, life-changing works come up, mediocre collection pieces will flounder and accordingly prices will stagnate.

This is bad news for artists and their dealers, since if the hunger for these artists subsides, then overall prices will crash, since it is the jubilance of high prices that begets high prices. In this sense, the economic value of art breaks away from its cultural value: the price of a Polke has nothing to do with the work as a cultural treasure and everything to do with the desperation of buyer who is willing to pay over the odds in the heady competition of the saleroom.

The unsold lots included four Richters. Yes, four Richters. Brett Gorvy, Christie’s head of contemporary art, wishfully attributed this catastrophic and unnatural turn of events to the fact that the works were ‘too intellectual’. Maybe they just were not very good, or maybe everyone suddenly cottoned on to the great scandal, but they certainly were not too intellectual. Anybody who operates within the commercial artworld inhabits a universe in which there are Richters floating around as freely as oxygen. Something that is produced on such a scale and appears in auction houses with clockwork frequency is unlikely to be overly intellectual: products of intellectual labour are hard won through toil and misery, not dashed off as quickly as the hammer hits the block. The mortifying truth here is that, for now, there is probably enough Richter floating around and even the market has begun to pine for something different. Moreover, Richter is still churning them out, so nobody this week need be in a great rush to buy one at auction.

The ailing YBAs had a rocky night, with two Sarah Lucas works, estimated from £100,000 to £400,000, failing to sell at all. Lucas’ Venice Biennale show has received a tepid, if not deafeningly cold, reception from critics, which may explain the failure of her work to budge. Perhaps, however, it is because some upstart of a philosopher wrote an article proclaiming the death of the YBAs and the entire saleroom was repulsed by these corpses before them. Jake and Dinos Chapman enjoyed a bittersweet triumph when their seminal Great Deeds against the Dead (1994), once owned by Saatchi and showed in ‘Sensation’, sold below low estimate for £422,500 to none other than their dealer Jay Jopling. Although it is a decent enough price for an artist who has a very scant secondary market, it is hardly an achievement when it’s your dealer protecting your prices. After all, protecting prices – and therefore your business interests – is very different from shelling out close to half a million pounds because you genuinely desire to own a work of art in and of itself.

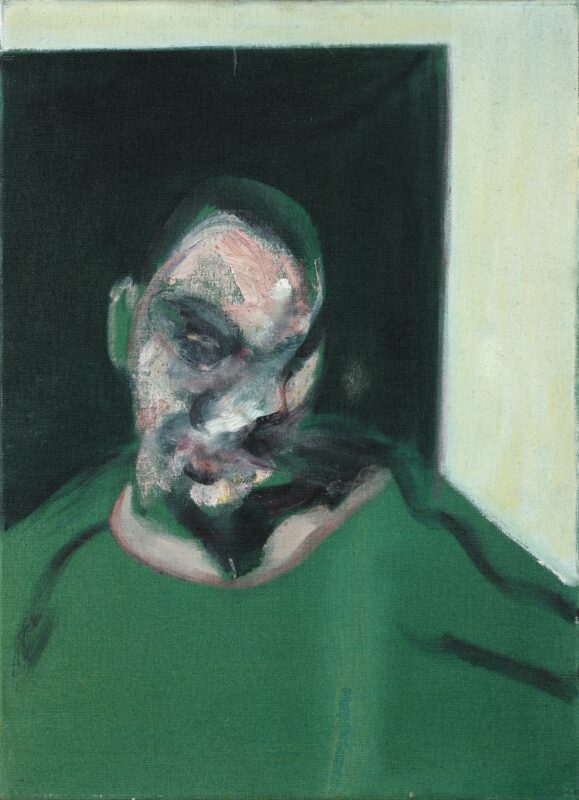

Over at Sotheby’s it was a yoyo of triumph and cataclysm. Andy Warhol’s first and only hand painted dollar bill, made in 1962, sold well above its high estimate for £20.9million. But then something mystifying happened, something so strange that it feels like we are free-floating in some kind of art market panic room of a cosmos. Francis Bacon’s Study for a Pope 1 did not sell. Not only that, but it fell flat like the dead weight of art itself under all that money, resolutely failing to attract even a single bid. Not one bid. No sale. Bacon unsold. It was bought ten years ago for $10million dollars and is widely thought to be one of Bacon’s crucial works from the pope series.

Normally Bacon comfortably tops the leader board, bringing in the top lots at auction, and the only reason for this is that he is very good; normally, he is the best in show, being one of the greatest painters of the last century, light years ahead of anyone working today and miles beyond anything else in a given sale. It’s one of those rare moments when the price – although ludicrous and unimaginable – somehow makes sense if you consider that true genius is priceless.

There is a surprising philosophical insight in all this: whilst the market is strong and the bubble floats inexorably on buyers are making fundamentally aesthetic decisions. It is no longer, or not this this time, just about having money to burn and the insatiable desire to own a stake in the artist’s brand; it is about owning a work of a certain ineffable quality that compliments a collection, that stimulates the aesthetic sensibilities in a way that no other work by that artist could.

This doesn’t explain why the Bacon pope was judged unattractive (although one suspects there is a dark secret about its provenance or some underhand dealing there) but it certainly explains the Polke, the Wool and the Richters. Perhaps the time has come when aesthetically substandard works by blue chip artists, or even by art historically important artists, can no longer find a home or realise the right price. The buyer has realised that they are in communion with an aesthetic phenomenon that has to chime, not with the endless clatter of the market, but with the taste and judgement of the beholder.

Words: Daniel Barnes