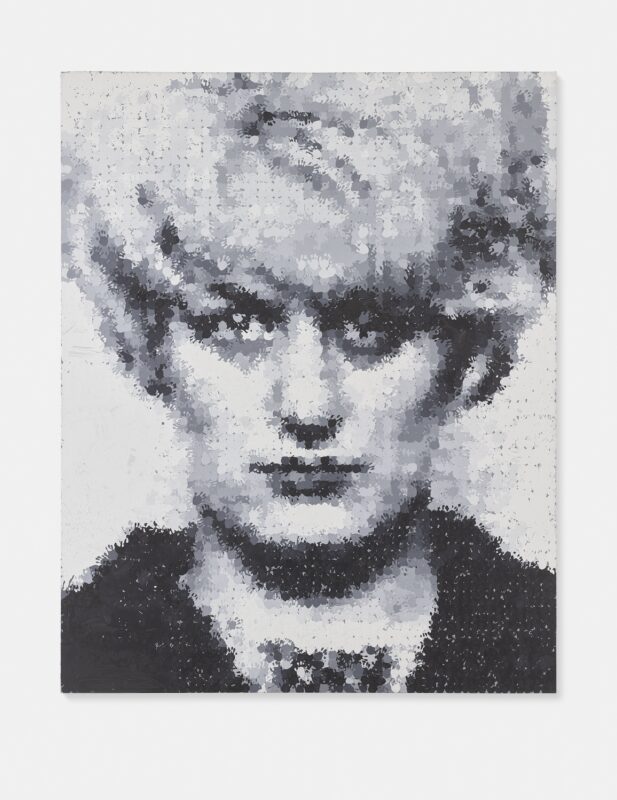

Stella Vine, ‘Pussy Riot Butterfly’ 2013 (c) Stella Vine, Courtesy The Cob Gallery

The big news of the week is that Camden’s super-cool Cob Gallery, headed up by Victoria Williams and Polly Stenham, has secured exclusive representation of Stella Vine. The gallery is making its London art fair debut this year at Art15 with a solo booth of older works by Stella, ahead of a possible solo show later in the year. This, and their gracious commission for me to produce a short text for their Art15 presentation, has promoted a lengthy reflection on the collision of art and celebrity. Stella, it seems, is the very thing that artworld secretly wants, and like every secret desire, resistance only makes only makes the prize all the more tantalising.

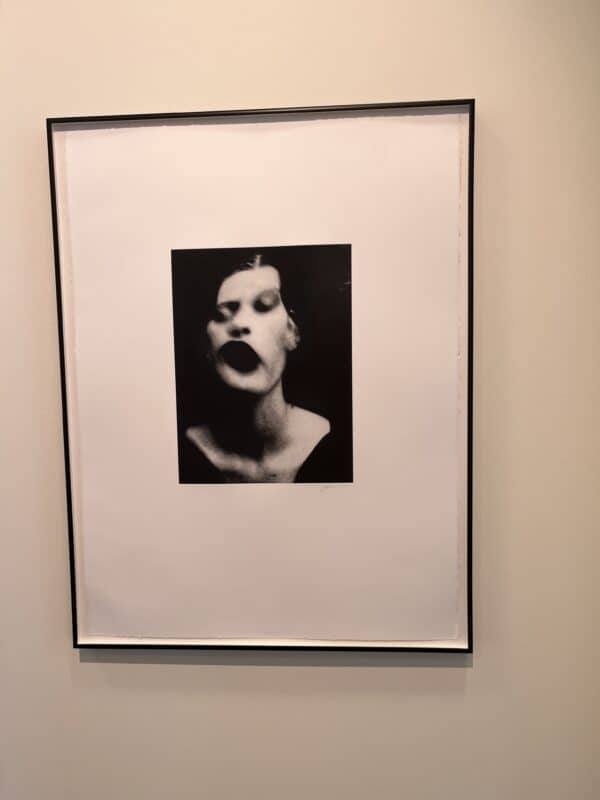

Stella Vine’s paintings unravel the myth of contemporary celebrity, gender stereotypes and identity. But they also offer an intimate, revealing view of herself, mastering the artist’s technique of looking inwards while looking outwards. It is as if every picture is a self-portrait, even though the face is of someone, and therein lies the unsettling power of her art.

Stella did not go to art school. She was a waitress, a cleaner, an actress, a single mum and a stripper, as the press never tires of reminding us. But she did take a few classes at Hampstead School of Art. In 2003, she decided to become her own gallerist, to learn the hard way, as she has said, ‘to be Jay Jopling’. A gargantuan task for anyone, not least a Northumberland girl who painted with the abandon of a child and the penetrating insight of a psychoanalyst.

Her big break came in 2004 when she sold some works to Charles Saatchi, whom she says she met for four minutes, including the iconic, Hi Paul, can you come over I’m really frightened (2003). This picture is symptomatic of her style, with its superficially naïve forms and sugary pallet depicting Princes Diana in mid-hysteria. There is something grotesque about the picture in the sense that the urgency of the painter’s hand and the wilful disregard for the rules of painting convey the true depth of the subject-matter: without all the affectations of form, perspective, colour and light the painterly illusion of pure unmediated aesthetic beauty fall away, and we are left with raw human emotion, an instant of human drama which can only end in inconsolable tragedy laid bare for all to see.

There followed a series of lucrative solo shows, most notably an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford in 2007 which included nearly every painting she had ever made. Stella had scandalised the artworld with paintings that revel in their deceptive surface of naivety; paintings, no less, of A-List and Z-List celebrities, instantly recognisable and yet curiously alienated from the tough exterior of fame, suddenly perennially vulnerable, damaged and human. In this conflation of the celebrity hierarchy itself, there is something deeply revealing, both about the fairy-tale of celebrity and about Stella herself.

Stella was suddenly everywhere and nobody could escape her brush: she has painted Amy Winehouse, Courtney Love, Kate Moss, Elizabeth Taylor, Chantelle Houghton, Pussy Riot, Sienna Miller and Amy Childs. All women who are equal measure heroic and tragic in their own ways, and yet in Stella’s hands the playing field is levelled so that all these women wear their fame as a curse and their unbridled humanity as a virtue with no distinction between their roots or destinies.

Stella’s feminism is in the way she challenges the constructed stereotype of the female damaged by brutal masculinity. Her women are, like herself, in the grip of an outmoded womanhood, with all its tenderness and terror in a merger of Elizabeth Wurtzel with the Spice Girls. Stella’s feminism is Girl Power and Prozac mixed up with an effort to reclaim the woman in art not as object or muse but as subject and master.

In the midst of these starlets in the dizzying cosmos of modern celebrity, the figure of Sylvia Plath looms large as the archetypal tragic heroine ruined by a man. The Plath myth is of the femme fatale who came to England on a Fulbright Scholarship, married a thrusting young poet, wrote reams of poems about her dead father and wound up her days in an oven in Primrose Hill. Stella paints Plath because she relates not to the myth but to the way that women are always prefigured by their myths rather than their art. For Stella, painting these women is an attempt to burrow beneath the myths and even to see beyond their professional output to uncover the struggling, cowering, terrified human being underneath the carefully constructed surfaces.

It is in this sense that one can see Stella’s paintings of other people as constant, unflinching iterations of the one self-portrait. She does not necessarily identify with her subjects as women or mothers or celebrities, but rather as individuals who have had their identities co-opted and battered by the world around them. In Stella’s world, we all give so much of ourselves to others just to get by that our selves – deep inside, behind the constant façade of the face – get lost in the seas of our public personas. Stella’s celebrity portraits express this deep concern in which the artist exorcises it for herself through the image of the famous, who are, after all, the common property of us all. The Princess Diana paintings, for example, seem to be about an essentially good woman in turmoil, buckling under pressure of the media spotlight, but really they are Stella’s universalised outpouring of grief over the death of her mother.

In Stella’s world, celebrity is just a means of pretending that some people are better or worse off than ourselves, but really fame is a meaningless fiction because underneath we’re all the same damaged, vulnerable human beings. But the fact that Stella paints them rather than us adds one final delicious conceit: celebrities are different from the rest of us because they are tarnished with the brush of fame and have to toil their demise in public, adding one more hurt to being human.

Words: Daniel Barnes