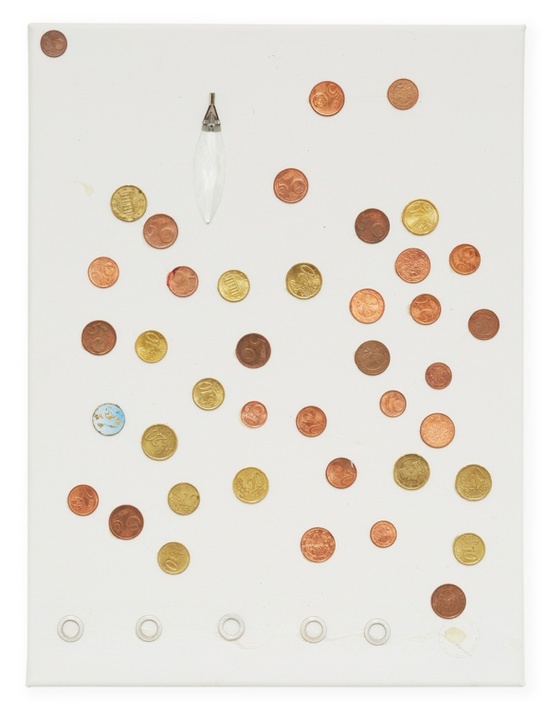

Isa Genzken: ‘Geldbild VVIII’, 2014

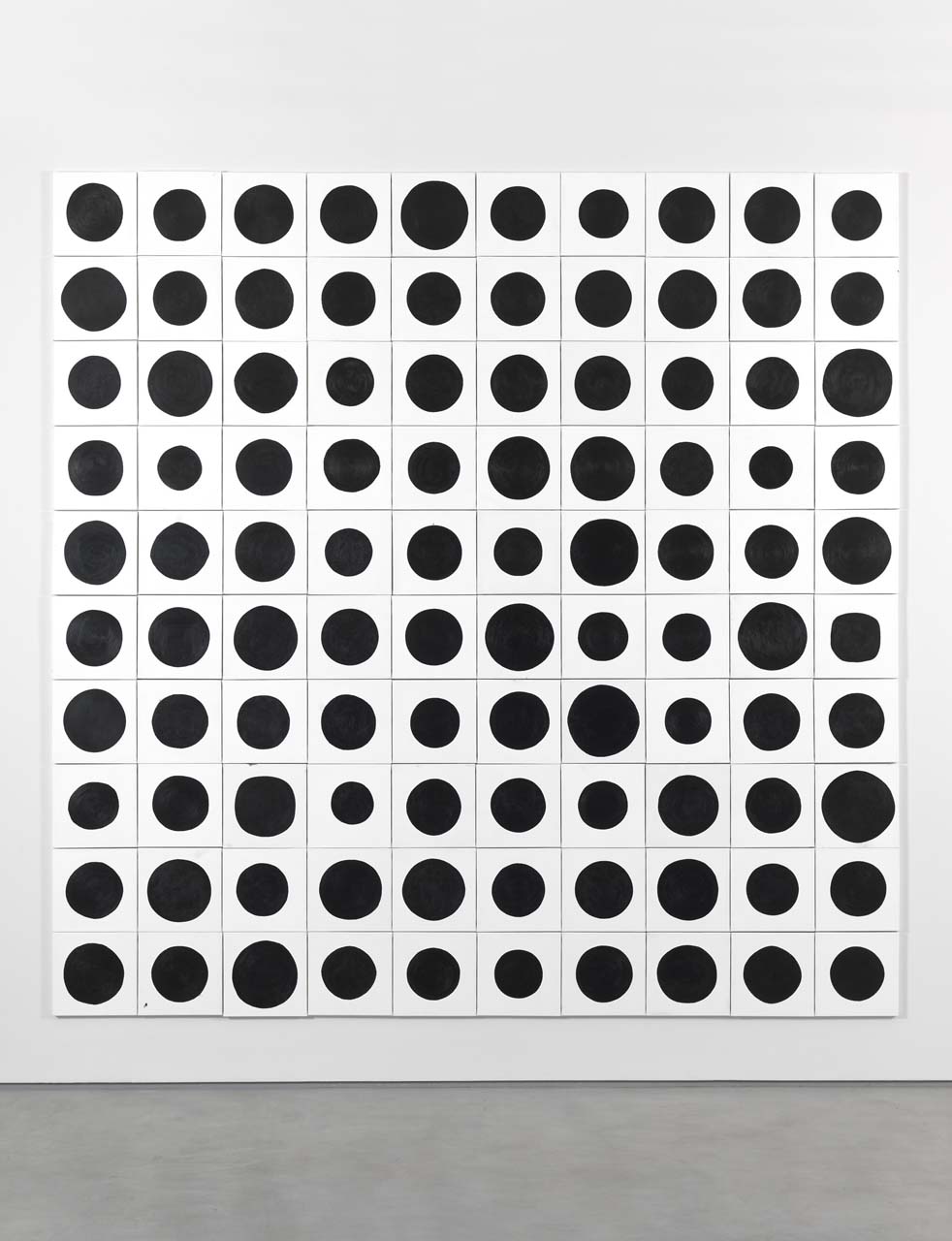

These two paintings are both made up of circular elements similarly distributed – 50 and 100 respectively. Neither involves the application of paint by the artist, but that aside the production processes are quite different. Isa Genzken (at Hauser & Wirth to 10 May) has made money paintings (‘Geldbilder’) most of which combine banknotes with coins, photographs of the artist and other material from the studio – a novel security issue, as a €50 note might well be worth detaching in an unobserved moment. One room – which I prefer – employs coins only to generate a more pared back and original abstract aesthetic. Their potential regularity is disrupted by somewhat haphazard application, the range of coins, the paint or tarnish on some, substitution of washers , and the odd coin being represented only by the mark of where it used to be. Meanwhile, one of the consistently sized 304.8cm square paintings – 10 feet in old money – in Jonathan Horowitz’s show (Sadie Coles to 30 May) was made by sending out a small canvas to 100 different people were asked to make an unmeasured free hand approximation of an 8 inch black disc. The variety of sizes so produced makes for a subjective riff on a early Bridget Riley or – more pertinently, given that versions of his mirrors are also in the show, Roy Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dots. Both counter the expectation that money is paid for skilful product of the painter’s hand: Genzken by making cash the subject and substance as well as one of the objects of the work; Horowitz by outsourcing the painting in the more radical way than does, say, Jeff Koons – it’s not that the substitution of others’ efforts is a practical matter to achieve production on the scale desired, nor that higher levels of skill can be bought in , but that the very effects the artist seeks would be lost were he to make the work himself.

Jonathan Horowitz: ‘One Hundred Dots’, 2015

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?