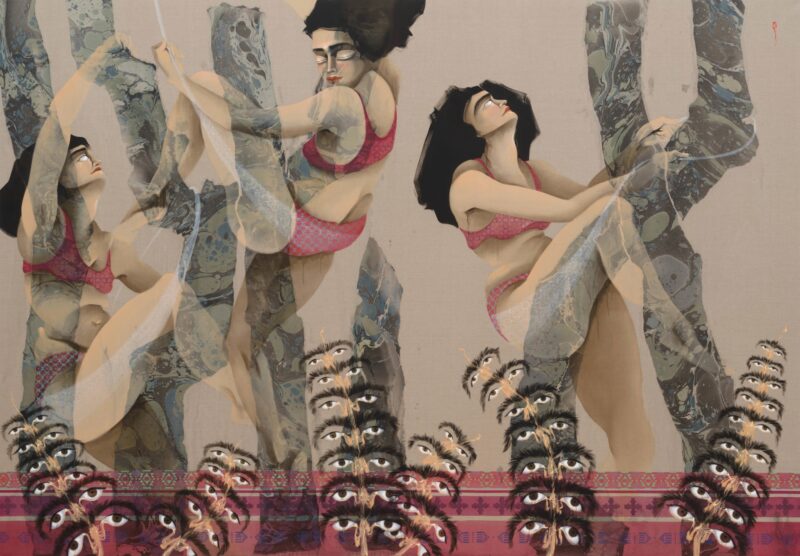

‘Patron: Experiments in Colour #2’ 2015 – Collaborative work in which Sinta Tantra paints Nick Hornby’s sculptural form.

Given that artists are brands of a sort, it would be no surprise if having the right name can impact on the chances of success. Ideally, I reckon, a name should be memorable, distinctive (so Internet searches lead to the artist rather than an ersatz name sharer); and easy to spell and pronounce – though a little bit of mystery does no harm, enabling initiates to feel they’re in the know (‘actually it’s Rew-shay’ / ‘Zee’ / ‘Yoost’, collectors of Ed Rusha, Sarah Sze or Jesper Just can point out). That said, Pierre Huyghe (say ‘Hweeg’) may have taken that a little too far, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul (‘a-pih-CHAT-pong Weer-uh-suh-THA-cull) has surely found success in spite of his name. ‘John Smith’, in contrast, fails the distinctiveness test comprehensively enough, perhaps, to be memorable: the filmmaker told me he knew he was gaining traction when someone referred to him as ‘THE John Smith’! Something which Nick Hornby (not the novelist, but the artist) must suffer in reverse. Ai Wei-Wei has cracked it, but Chinese artists are confusing for Westerners – I struggle to separate my Liu Xiaodong from Chen Xiaoyun, my Xu Bing from Lu Ding. It makes you wonder why more artists don’t change their names, as did, say, Marcus Rothkowitz, Vostanik Adoian and Alfred Schulze*. So what is the ideal name? Damien Hirst has a good one – simple yet unusual with thematic hints of devilry and death (is a car-driven coffin ‘hearsed’?). And Blue Curry, Rae Hicks and Sinta Tantra, for example, are young British artists who won’t be able to blame their names if they don’t become famous.

* Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky and Wols

‘Patron: Experiments in Colour #2’ 2015 – angle 2

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?