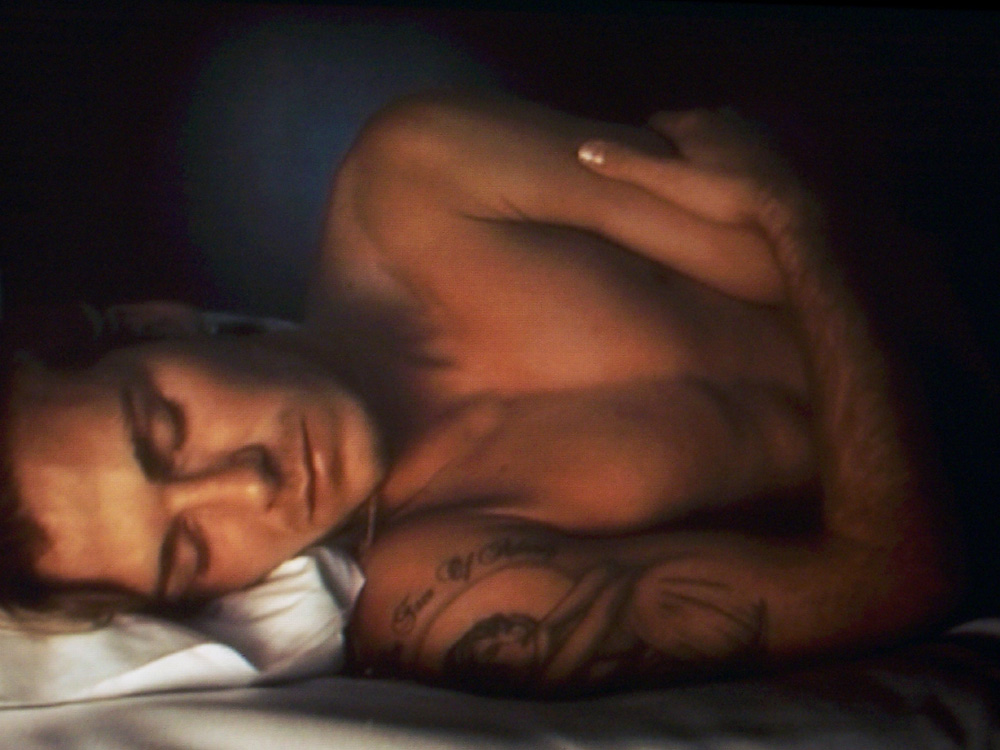

Sam Taylor-Johnson’s video of David Beckham sleeping is the perfect portrait of the perfect brand: it captures a man in the most natural, compromising position of unconsciousness, where there is no scope for posing but only the unadulterated swell of humanity, warts and all. Except there are no warts, only luscious locks of blond hair unfurling over a golden, firm body and the transcendent peace of a man who sleeps with a slight cheeky smile. People often ask me how they can become famous, successful and rich artists without selling out and I think I’ve found the answer in an unlikely place. It’s all very well writing a weekly column about how expensive art is the key to enlightenment, but the real lessons about value are to be found in David Beckham.

In the interest of full disclosure, I, as a lowly philosopher, know nothing about football except that it is an excellent way of spending quality time with my dad and that it involves a delicious combination of beer, shouting and lads in shorts. What I do know, however, is how popular culture has a remarkable way of concealing deep truths behind a veil of simplicity; I also know that value is constituted by the price someone will pay for something according to how important they regard it to be.

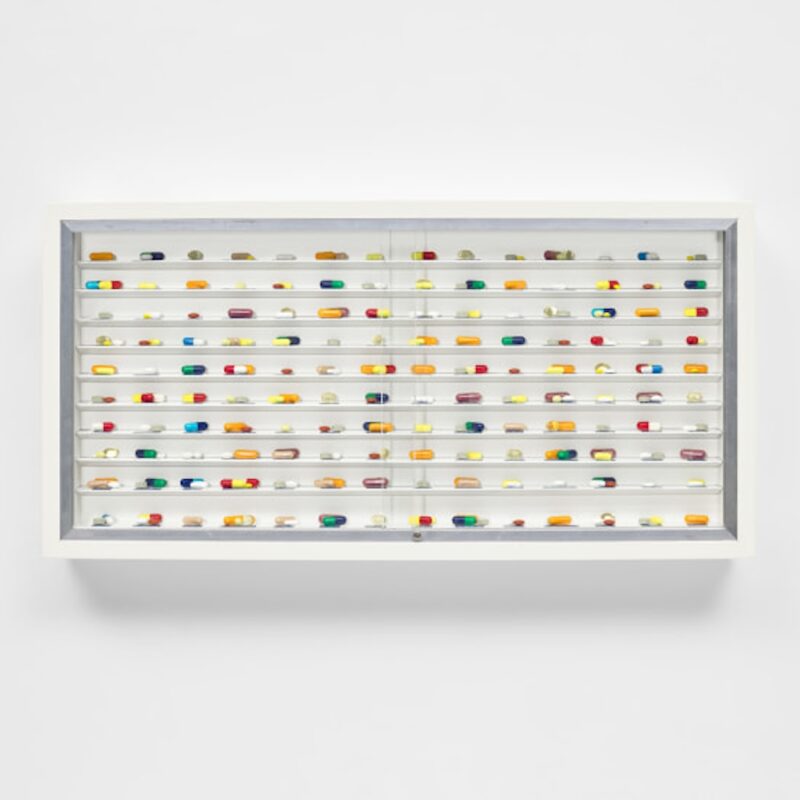

Value in art comes down to a disarmingly simple question: is it worth it? It is a matter of whether $58million is a fair price to pay, in monetary terms, for a Jeff Koons balloon dog and whether, in cultural terms, it is so art historically important that it justifies that price tag. To make a few sweeping generalisations that there is not space to defend, it is doubtful that an oversized orange steel model of a balloon dog is worth that much, but it is entirely feasible that a dead sheep in a tank of formaldehyde is worth a mere £3million. A Richter abstract is worth every penny, but a Murillo is hardly worth the canvas it is painted on. The logic here is twofold: first, that price reflects the cultural kudos and art historical longevity of the object; and second, that the overall aesthetic experience of the work is effectively priceless. And yes, the implication is that Koons is a poor-man’s Warhol whose contribution is fleeting, whereas Hirst is a maker of genuine magic.

David Beckham, whose salary in 2013 was £3.4million, is worth every penny anyone has ever paid him to kick a ball, to take his photograph or just to put his name on pants and fragrances. In fact, he is such good value for money that he makes discerning value look like an objective science. You can argue about Hirst until the cows break out of their formaldehyde tanks, but Beckham is the golden bollocks.

In her insightful book, Burchill on Beckham, Julie Burchill investigates the monumental success of an apparently stupid boy, who enjoys copying cartoon drawings of The Lion King and whose effeminacy was only vindicated by the invention of the term ‘metrosexual’. Her answer is that he kept his head down and concentrated solely on the thing he was good at, eschewing boozy lads’ nights out and girls. But the knock-on effect was that English football changed forever: Burchill points out that when footballers were paid pocket money ‘they seem like real men; the minute they got a man’s wage, they became Lads; then, when they got a king’s ransom, they became little boys’, but this didn’t happen to young David from the block. Football, she says, is just a game boys play, but it has dignity when done for a pittance at the same time as denying yourself the kinds of pleasures boys usually indulge in. Beckham’s achievement is to have given up everything, taken a king’s ransom and somehow still brought dignity to the game; he has bypassed the crisis of masculinity with his sarong and perfect, ever-changing hair in order to become an icon, not just of football, but of the modern man.

With his childlike nature, keen sensitivity, good manners, dashing good looks and well-honed talent, Beckham is the ideal brand that can be effectively marketed to both men and women. For men, he is the epitome of aspirational grooming and working class hero of the football pitch, and for women, he is beautiful and a loving, devoted husband and father. His footballing prowess lends him to any team and his good looks lend his face to any product. The only glitch in the Beckham machine, that affair, passed and everyone – especially his wife – forgave him in an instant. Even when he gets it wrong he somehow remains flawless, pristine, untouchable. He told the boys they could be fussy about their hair and still bag a Spice Girl and he told the girls that a man could be a professional footballer and still do the majority of the housework.

The fact that Beckham’s track record, not the mention the man himself, is so unfathomably perfect makes him worth the money in a way that Jeff Koons can only dream of, since every time Koons makes another one of those balloon dogs you doubt the integrity of the hoover pieces, whereas even if Beckham commits an indiscretion you just have to re-watch one of those goals or look at the H&M ad to see that nothing can dent the impression of endless success. Beckham’s high value can also be explained by a maxim of Sir Alex Ferguson, who according to Jon Snow ran Manchester United like a Stalinist outfit: ‘some people think football is a matter of life and death, but it is much more serious than that’. People’s – entire nations’ – hopes and dreams stand or fall on a football match to such an extent that the World Cup is basically a matter of public order and national security. So no amount of money for an exemplary footballer like Beckham could ever be too much if we don’t want to find ourselves at war with France after all the goals went in at the wrong end.

If value is the price someone will pay for how important they think something is, then nobody ever undervalued Beckham. There is basically nothing wrong with him: he excelled in his chosen profession, which happened to be The Beautiful Game, crystallised more than his fair share of history, shared out the bounty of his wealth, talent and marketability to charities and corporations alike, and then he ducked out quietly to raise his kids. The goal for any artist who aspires to fame and success, then, should be to emulate Beckham as closely as possible. The trick is to work doggedly at your craft, either giving up your vices or be able to hide them completely, and to pay due care and attention to everything else like family, money, charity and generally being a decent person. The Beckham formula boils down to one simple principle: if you are going to sell your entire self as a brand, make sure every fibre of your being is worth every penny. And if you absolutely must take your clothes off, ensure that you look on some level irresistible to everyone, regardless of stuffy social conventions.

A lot of artists stray from their central talent, like when Gary Hume gave up the doors, or they allow everything else to suffer for their art, like Pollock. Beckham shows us that you can have everything and do anything so long as you balance work and life with passion and devotion. Hirst is a long way from it, but closer than Koons for sure, but someone like Hockney is the Beckham of art – talented, demure, focused and resolved. Beckham shows us that you can be filthy rich and good at what you do if only you realise that all that glitters is the entire horizon of your world and not just some inert goal that you run towards as if nothing else matters.

Words: Daniel Barnes