In the run up to the general election, the Hayward Gallery is attempting to decode Britain’s present by having seven artists each curate a section that explores our cultural history. The show revolves around a difficult relationship between social and cultural history. They are connected by memory, events and objects, but they are not thereby symbiotic because artworks and mere artefacts of historical significance are ontologically different things; and in that differences resides a sovereign semantic tension which dictates that one can only illuminate the other at the cost of its own sacrifice. In the final analysis, it demonstrates – as if 20th Century philosophy had never happened – the difference between artworks and mere things.

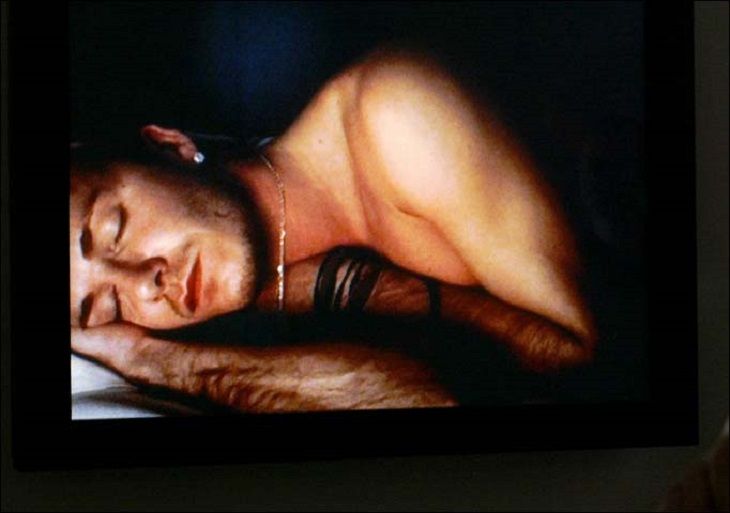

In Simon Fujiwara’s room, a household broom – not a clever conceit of Martin Creed or Jeff Koons – sits alongside Gavin Turk’s and Ceal Floyer’s bin bags; the flimsy art historical joke implied here withers immediately. The broom was actually used by a real human in Hackney to sweep up after the 2011 riots; the bin bags look like domestic rubbish, but they are important works of art. In this context the broom is too banal to emit any of his banal historical significance, and what dusty old broom wouldn’t be shown up by an immaculate bronze cast of a bin bag? Together they just look silly, as if a petulant undergraduate is trying to say that modern art is rubbish and everyday life is beautiful. Is it a comparison or a juxtaposition? The question is rendered irrelevant by fact that David Beckham’s naked flesh is glinting in the corner of your eye as you consider it. Sam Taylor-Johnson’s sleeping Beckham remains one of the most moving, delicately observed, appropriately creepy portraits ever made.

Fujiwara also tries to remind us of Thatcher, but only ends up jolting cultural memory as far back as The Iron Lady because instead of recalling the 80s with a real Thatcher dress, he has used Meryl Streep’s costume from the film. The Thatcher years – a significant period in British history – is thus annulled by a thin piece of popular culture. It is clear that the idea is that historical memory is mediated by culture, but it fails because it merely states the obvious and in this case the history is more interesting than the culture.

Fujiwara’s room has an otherworldly, clean aesthetic: everything – including paintings – on white plinths which are laid out in a grid across the room. It feels like a mortuary with the various corpses of history laid out waiting for an autopsy to take place. But this only confuses the issue because it is not clear, as with the dress and the broom, whether it is art or history. A Spot Painting lies flat on its plinth, encased in Plexiglas, as if it is a relic of some bygone era; treating it as an object in this way unravels everything Danto achieved in distinguishing artworks from mere things.

If art and mere objects were the same, they wouldn’t play such markedly different roles in our lives, and if we could not tell the difference between them, the artworld would cease to function. But they are different and we can tell the difference. The difference – as Danto said – is that art is defined, not by something you can see, but by an atmosphere of history and theory that makes it what it is: an unmade bed is art because its creator has a theory about how it functions, but no amount of theory tells us how a mere bed is a useful thing to have. This is the great stumbling block: art has its own history to contend with, which muddies the water when we are trying to get a clear picture of social history. A Spot Painting might recall a time in history – perhaps very vividly – but it makes so much art historical noise about painting, the great art boom and celebrity artists that you can hardly hear the dim mummer of the Major years.

Sam Taylor-Johnson, David Beckham Sleeping (2002)

There are good moments when the weight of history bears down so heavily that it is suffocating, such as Roger Hiorns’ obsessively detailed investigation of Mad Cow Disease. Or the massive ground-to-ground missile launcher in the courtyard, poised for action with the entirety of London as its target, reminding us that another cold war only warmed up when democracies started telling tall tales about mystery weapons. Hannah Starkey’s room is an absolute triumph precisely because photographic images of historical events are tied up with artistic concepts. She has selected works that document moments, tensions, triumphs and nuances of emotion that give enough away to follow a narrative line but conceal enough to leave the viewer some interpretive legwork, just as both art and history should do, whereas elsewhere there is not enough room to contemplate or interpret.

But then, right at the end, Richard Wentworth gives you Bacon and Hockney, and the blissful relief is just how you imagine that hard-won shot of methadone to be. Wentworth’s room is a dazzling, beguiling treasure trove of wonders: he seamlessly hangs an entire wall with papers from the Archive of Modern Conflict in the same room as Paul Nash, Lowry and Tony Cragg; the room is bursting with sculptures and objects in vitrines, the walls are covered like a salon. The old and the new, the art and the non-art, sit comfortably side by side so a portrait of post-War Britain begins to emerge without even trying.

And then you realise that the problem with the whole exhibition is a poverty of style and intellect: the other six artists have curated their rooms in such a way as to try to make history look like contemporary art or a history lesson appear to be an exhibition, which doesn’t work because the historical artefacts are not artworks and the artworks are so much more than historical documents. It is an intellectual failure to engage with the nature of the objects on display as artefacts which are – socially, conceptually, ontologically – utterly distinct from artworks. Wentworth avoids this by purely stylistic means because he throws it all together in a jumble, making it look more like you’ve walked into a museum store room than an exhibition. This managed disorder enables the viewer to explore, discover and judge for themselves what artworks and documents can tell us about where we are now.

Words: Daniel Barnes