This week Ed Milliband said that a future Labour government would place the arts and the creative industries at the heart of its mission. It sounded a lot like something we wanted to hear, but in reality it was a crass bit of electioneering. It misses the mark by quite some margin, but it does help us to glimpse what we need to do about the state of the arts.

In a speech to the Creative Industries Federation, Milliband bemoaned the decline in students taking GCSE art, music and drama, and an 11% drop in arts school teachers. With the arts at the centre of education, Milliband promised that ‘Schools will only be able to receive an ‘outstanding’ rating if they offer creative subjects and cultural opportunities within a broad and balanced curriculum’. He even went as far as to say that the creative industries and arts institutions should offer more apprentices ‘in return for direct grants or major government contracts’.

The idea, insofar as there is ever an idea at the core of Labour’s pronouncements, is that culture enriches the lives of individuals and boosts the economy. The decline of arts education in schools has run parallel with the government’s gradual chipping away at nationwide arts funding. According to the Warwick commission report on the future of cultural value, published on Tuesday, the creative sector represents 5% of the British economy, valued at £76.9billion. It also highlights how audiences are overwhelmingly white and middle class, alongside a more general drop in participation across the arts. The report concludes that the steady decline is linked to education and funding policy directed by the current government. The report chair, Vikki Heywood, said ‘if you fiddle around with the education system at one end then something goes wonky at the other end’.

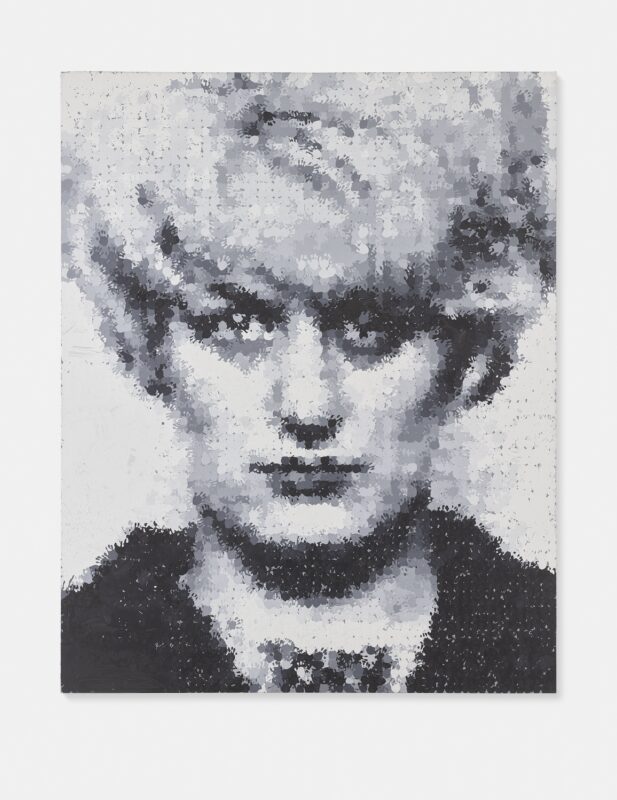

The artist Bob and Roberta Smith, who is standing against Michael Gove in his Surrey Heath constituency, has been campaigning tirelessly for the arts for some time. To those of us on the inside, the predominantly white middle-class artworld that is sorely lacking in funding, educational infrastructure and due recognition by government is not news. But the artworld also has to take responsibility for its share: in an artworld dominated by high-rolling auction houses and mega-galleries there is no concern or conceptual space for the humanity of art as something that should be available to all. Art is a sovereign good, and as such it is a universal right. The situation is doubly alarming as it sounds the death knell of the 90s whose serendipitous triad of New Labour, Britpop and the YBAs wildly transformed art from a stuffy bourgeois pursuit of the few to a classless participation in contemporary culture for everyone. Although David Cameron has not killed art – a crime committed by deep recession – he has finally signed its death certificate with years of cuts and neglect.

But that does not mean that all is rosy in Milliband’s Labour camp for criminally sycophantic optimists. It’s great that Milliband wants to improve access to the arts for school kids, but it is a cynical election promise that simulates doing the right thing while skilfully ignoring the real issue. The real problem is that everyone, not just kids, has forgotten just how important art is: austerity in government policy at one end and all the money in art at the other end has disenchanted art of the magic that makes it valuable, and Britain has fallen for this disenchantment.

We need arts education across the board, not to teach people how to help the economy – we can leave that to Gagosian – but to reawaken passion for the arts. At the same time as widening access to the arts for schoolchildren, we need funding and facilities for adults and entire communities. Moreover, we need to foster art appreciation and aesthetic engagement. We need to understand, for example, why it is that you have not experienced art properly if your iPhone is permanently stuck between your eyes and the artwork. This is a deep philosophical matter of aesthetics, for sure, but it must have a 21st Century solution, which it is the business of art educators to apprehend.

Gone are the days when we lived in a society polarised by the humanities and the sciences. At the tail end of postmodernism’s project to flatten the contours of culture, the advent of digital technology irreducibly fused the humanities and sciences. It is for this reason that Milliband conspicuously talks more about the creative industries than he does specifically about art and why craft and dance creep to the fore of his discourse. ‘The arts’ is now more than painting and sculpture, but also more than pickled sharks and unmade beds – it is a luscious combination of all the humanities and sciences in the palm of everyone’s hand.

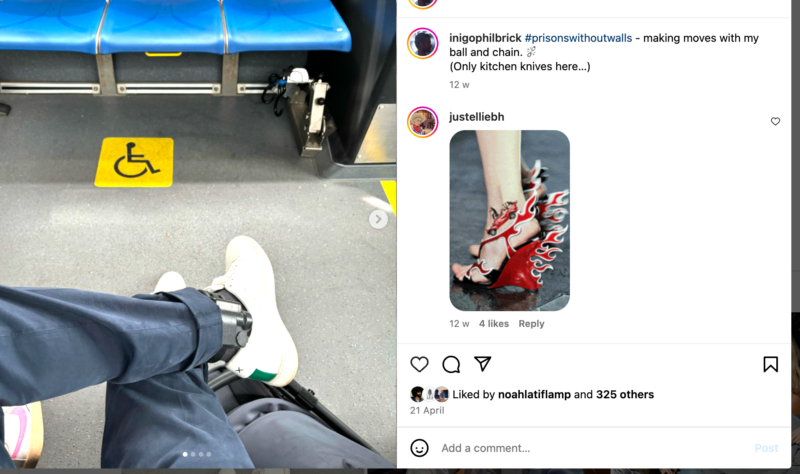

As such, it is incumbent upon us to teach art as it actually is here and now in the cradle of the 21st century. This means that art education needs to ensure students are attuned to and prepared for the reality of art as it is today. We need to understand art as all the things it traditionally was, but also as entrenched in the internet, capitalism and utterly at the mercy of every idiot with an electronic device in their pockets. In short, Milliband might want to teach kids to draw or to appreciate a Rembrandt, but he also has to teach them that an Instagram photo can be a work of art and how to make millions at auction. It might seem stark, but that’s the reality of it, and nobody wants the next generation to grow up in a fairy-tale land of the distant, inert past.

Art education, in any sector, needs to forget about knowledge – which has become the 21st century commodity to such an extent that its cultural currency is utterly devalued – and focus on passion. It is passion, and passion alone, for the arts that drives people to do things that matter. What Ed Milliband is doing matters, but it is not driven by passion for the arts, so we need to pool our resources and energies, to make art matter again before it slips from our grasp and forever becomes the plaything of the One Percent. We need to rediscover art in and of itself, as culture, pleasure and enlightenment just as we did in the 90s, but this time it is going to take more than a charismatic champagne socialist and the simple joy of sharks and Nazis.

Words: Daniel Barnes