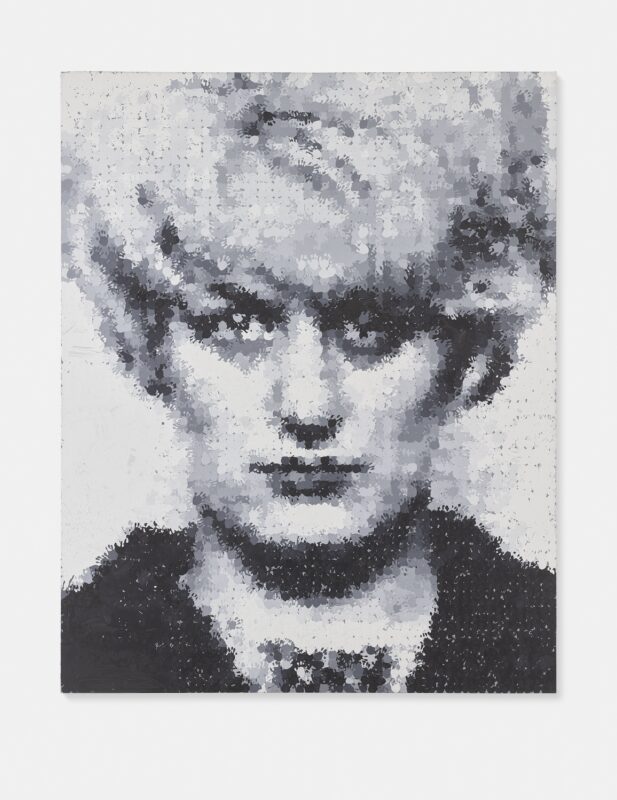

Jackson Pollock painting ‘Alchemy’, 1947, by Joe Figg (c) the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, 2008

Jackson Pollock is currently the subject of a show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, where one of his earliest pour paintings, Alchemy (1947), is the centrepiece. He will also be centre stage this summer when Tate Liverpool opens an exhibition of the relatively neglected Black Pouring paintings. This is one of those moments when an icon of art history reveals previously unseen depths.

Pollock defined the battle lines for modern art. He challenged it to deal with the 20th Century by pushing the boundaries of his discipline but retaining its sensuous materiality and imbuing it with the expression of human sentiment. And he did this in that crucial window between Duchamp and Warhol, where art was no longer what it had always been but it was not quite anything at all, so he acted with both artistic freedom and in danger of critical retribution. For all his genius, however, he was also a volatile drunk; those masterful paintings do not just bear the sweat and tears of Pollock but also of his friends and lovers, not least his wife, Lee Krasner who suffered for her husband’s art.

The Tate show, ‘Blind Spots’, investigates the period from 1951 to 1953 in which Pollock experimented with pouring black paint directly onto the canvas. These substantially monochromatic works, lacking the carefree, melodic loops and drip, are stark, brooding paintings. They suffocate the canvas, pulsate from its surface and draw the viewer in to a quixotic search for meaning, revealing a Pollock stripped of colour and lurching towards the abyss. But the exhibition will also feature some of the sculptures Pollock was working on until his death by driving into a tree in 1956; indeed it will be contextualised by the fact that he did not make a single painting in that last year, but only worked on these wire mesh and plaster sculptures. It will add a new dimension to the Pollock image, slotting sculpture in at the end of a career built on painting, as if it were his elongated death throes.

The Guggenheim show reveals something else entirely; it unveils a freshly cleaned seminal work and in the process potentially shatters a romantic myth. Alchemy is one of the earliest examples of Pollock’s pouring technique, consisting of layers of enamel and oil paint in nineteen pigments, along with twine, sand and pebbles. Prior to its exhibition at the Guggenheim, it had been at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence for extensive cleaning, removing more than sixty years of grime that had accumulated and dulled its surface. For the first time visitors can view the painting without glass, giving unprecedented access to the work’s intensely sculptural surface and radiant colours with all its aggressive, but somehow rhythmic, abandon.

During the conservation, a non-invasive scientific analysis revealed a startling new piece of information. The analysis revealed that the seemingly random drips, pours and splashes are based on a grid configuration that guided the order of composition, delicate traces of which can be seen in white paint. This is surprising because it threatens to overturn the dearly-held myth of Pollock the frenetic paint-thrower whose only guide were the vagaries of his turbulent emotions. It can, of course, only overturn this myth of it can be roved that Pollock, once he got the hang of splashing paint all over the floor, continued to use this grid. It is entirely possible that he abandoned it once he became adept at something your child could do.

This new information is a stunning challenge to the orthodoxy, but it should not astonish us if we think for one moment that Pollock was an artist, not an angry toddler or an incompetent drunk. Once, in his early days as an artist – that Pre-Drip Pollock who is almost entirely forgotten – he made figurative paintings, albeit with a fashionably daring abstract inclination, which required the patience, skill and method of the artist’s timeless craft. There is no reason to think that he did not apply these principles to abstract expressionism. Even if what we see on the canvas appears to contradict that, art must always appear to be the perfect crime; the artist covers his tracks, leaving a beguiling conjuring trick. And when asked about process, if he has any sense and any respect for the secrets of his trade, he will lie because he knows you can’t have the truth and something beautiful.

Words: Daniel Barnes

‘Alchemy by Jackson Pollock’ is at Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, until 6th April 2015.

‘Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots’ opens at Tate Liverpool on 30th June 2015.