Rembrandt: Juno, 1662-5

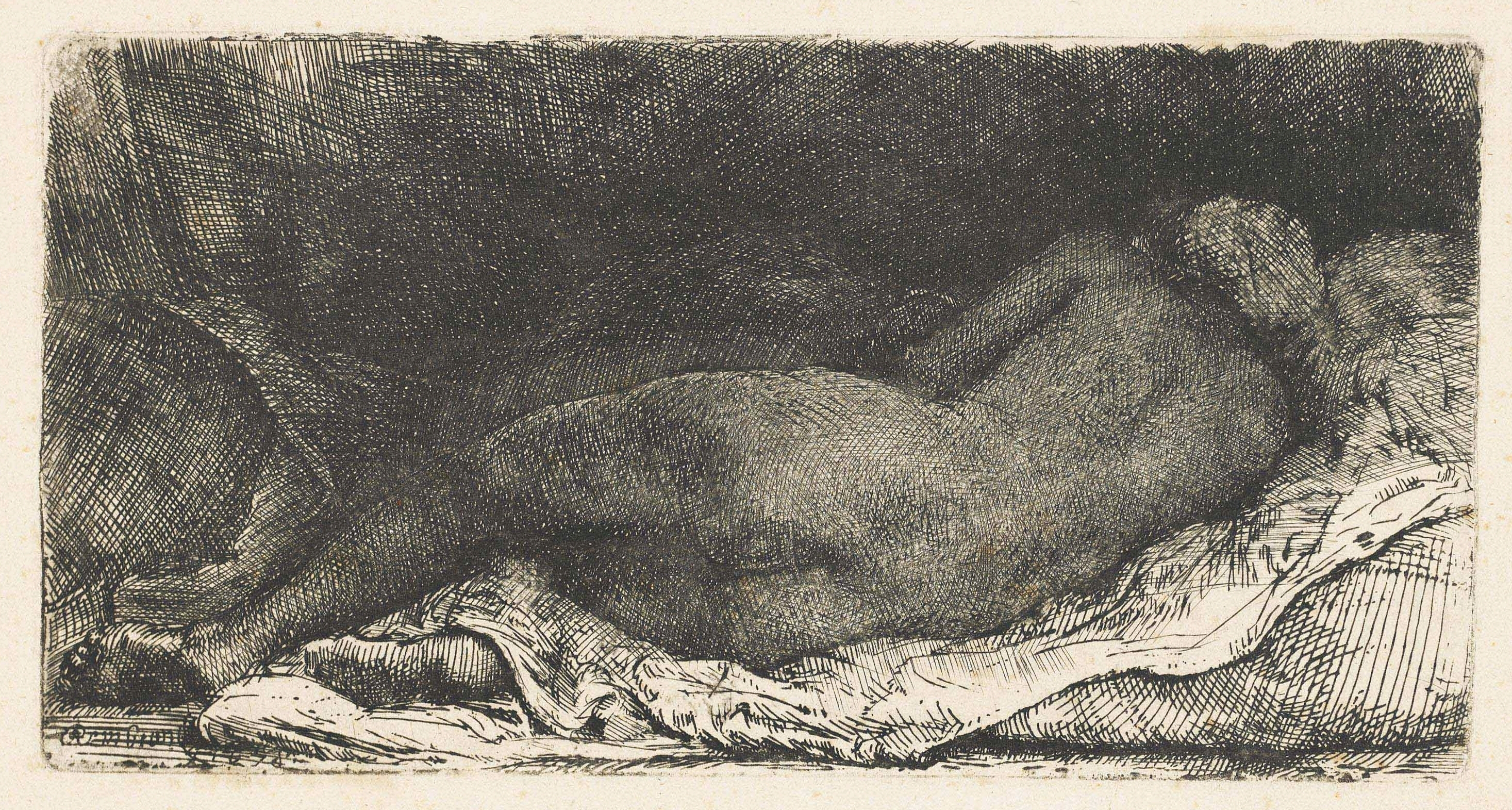

Rembrandt is known, of course, for his crepuscular tone and his ability to draw symbolic and emotional meaning from shadows and darkness relieved by telling illumination. Presenting the 40 paintings, 30 prints and 20 drawings of ‘The Late Works’ in the National Gallery’s windowless Sainsbury basement rooms (to 18 Jan) emphasises the point. All the same, my wife and I were struck, as we mentally tracked back across our shuffle through the end-of-run crowds, by the thought that – whatever might have been in the mix of the sombre browns and glowing ambers – we could recall no visible straight yellow, green or blue. Even when Rembrandt paints a parrot (‘Portrait of Catrina Hooghsaet’, 1657) and a peacock (‘Juno’, 1662-5) he manages to avoid such hues. The show is a stream of well-presented masterpieces, so that’s more observation than complaint, though one area of darkness somewhat under-illuminated was the accompanying booklet’s apparently contradictory claim that the reclining nude ‘La Négresse couchée’ (1658) might represent not a black woman but a white one in heavy shade – without mentioning that the title isn’t Rembrandt’s, but that given by Adam Bartsch, the Austrian scholar of printmaking, in 1797. That said, Jonathan Jones in his Guardian review swallows Bartsch whole, stating plainly that ‘in one erotic etching he portrays a black woman naked. He loves her difference’. Either way, it’s a typically sumptuous etching and drypoint in which the last thing we miss is chromatic colour.

Rembrandt: Reclining Female Nude (‘La Négresse couchée’), 1658

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?