Jeff Koons, ‘Balloon Monkey (Orange)’, on show at Christie’s HQ, Rockefeller Plaza, New York

A spectre is haunting the artworld. In the foyer of Christie’s New York, at over twelve feet tall and made of painted steel, Jeff Koons’ Balloon Monkey (Orange) (2006-2013) presides over daily business. It looks like another monumental sculpture, but this ubiquitous figure is so much more; according to Robert Storr, it is a grisly metaphor for the art market – an inflatable thing that cannot be deflated. After another buoyant year in contemporary art sales, the market bubble shows no sign of bursting, but at what cost to art?

If we were gauging the health of the art market with a version of the Currency Susan, in 2014 it would have been a sultry but gregarious Susan. In November, four days of auctions in New York raised a staggering $1.66billion. We have grown so accustomed to the astronomical prices and the superstar artists that art, which should be surprising, now fails to surprise at all. Charlotte Burns, writing in The Art Newspaper, points to three ways in which this economic boom seems as if it should lead to cultural bust.

First, the fact that commercial galleries occupy prime real estate in London, New York and Paris means that the pressure is on artists to make big expensive work to fund their dealers’ lavish property investments. Second, the demand from collectors is so high that artists are too preoccupied with fulfilling orders for their classic pieces that they scarcely have the time or space to create meaningful new work. And third, the dynamic of supply and demand has almost entirely closed the gap between the artists people are talking about and where the money is going, so critics no longer head an industry of ideas in which there is a distinction between who is interesting and who is performing well on the market.

If artists are merely making work to fund the existence of galleries, demand from collectors is obstructing the creative process and there is no longer a critical distinction between aesthetically interesting and commercially successful art, then it would seem to be the end of days for art. These three things – which are very real features of the contemporary artworld – fly in the face of our pretheoretical view that art occurs for reasons other than financial gain. Art, on this grim view, has reached its terminal crisis: co-opted by a few megalomaniac gallerists, it can no longer perform its social function to provide intellectual respite from the madness of human striving; and artists, seduced by the promise of riches, can no longer say no to artistically unsound but financially delectable propositions.

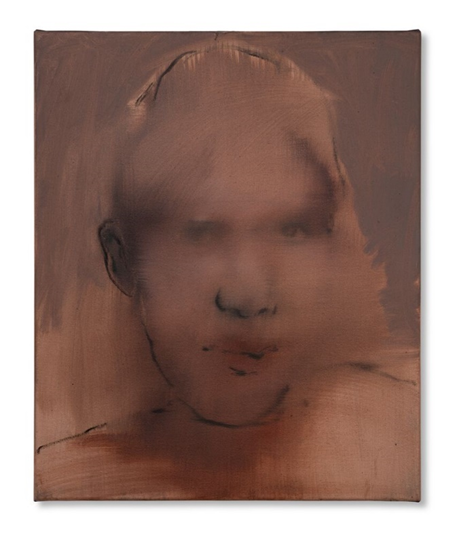

Sometimes an artist will try to resist the market commodification of their work. Wade Guyton performed an ontological trick on his Untitled (2005) by reprinting multiple copies right before it was sold at auction in May 2014. Sudden, unanticipated abundance was supposed to devalue the work by illustrating the mechanical reproducibility of the artform, thus demolishing the uniqueness that Chrities’s was trading on. But collectors are not careful metaphysicians and auction houses are Cartesian evil demons, so Guyton’s stunt did nothing to quell the desperation in the saleroom. It still sold for $3.5million.

Wade Guyton’s ‘Untitled’ (2005), reprinted multiple times

Resistance seems to be futile because the market’s astonishing indifference to the cultural value of art leads it to treat artworks as indistinct commodities; the Guyton, for example, is denied its ontological status as a mechanically reproducible work, which is what makes a particular instantiation valuable, thus side-lining to economic concerns the central aesthetic interest of the artist’s practice. This represents a serious threat to art, but it is no good looking to the market to neutralise it; rather, it is up to artists to do something to shake market confidence, as Guyton did, but this can only be the preserve of those who no longer need the market. Critics can also play a meaningful role here by elucidating a critique of Tara Palmer-Tomkinson: whilst money buys good cocaine and Cashmere, no such rule holds for art, where price and quality silently divorce under the racket of the auctioneer’s hammer.

The balloon monkey with which we began is an impeccable illustration of this state of affairs. It was commissioned by collector Frank Cohen, who could not resist its gleaming surfaces and epic proportions, but when Koons finally finished it Cohen discovered he did not have room to house this exotic beast. Although Cohen’s pockets were deep, his eyes were bigger than his gallery’s stomach, so the work had to be sold on immediately as so much surplus value. And so the market, like collectors’ desires and blue-chip artworks, just keeps inflating and there is nothing, not a pin of practicality or respect for the distinctness of culture, that can deflate it.

Art will survive this dominance of the market precisely because it is necessary whereas the market is only ever contingent. The current state of the market and its stultifying grip on art is a result of the often repeated fact that the great crash of 2008 did not change the fabric of capitalist societies. It only rocked the boat as we sailed through a stormy patch, ultimately leaving the rest of the ocean untouched. The balloon monkey testifies to that resilience, but its very opposition to all that we think art is truly about is a reminder that, when the celebrations are over and all the animals have escaped the menagerie, art transcends the market and all that is solid melts into air.

Words: Daniel Barnes