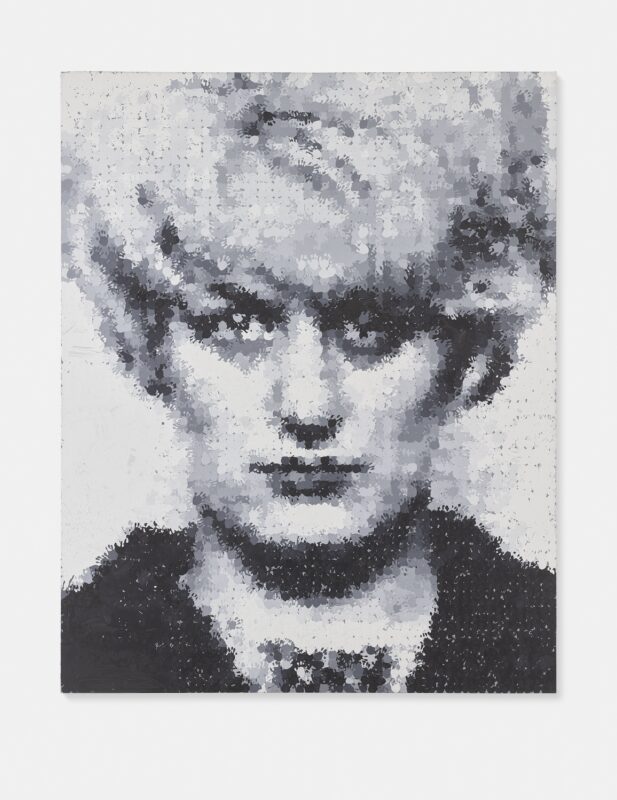

Duncan Campbell, winner of the Turner Prize 2014

Ever since video killed the radio star, it has acted with impunity. Its latest crime has been to gorge on the Turner Prize. It is not that Duncan Campbell is not a worthy winner, but that video does not necessarily make good art, even if it does make common entertainment. It only proved that the Turner Prize’s powers are waning, along with its critical edge.

The difficulty with this year’s shortlist, precisely as Adrian Searle has pointed out, is that some of the work is not as resolved as it should be for a competition at this level and it feels as if the judges were primarily concerned to make a cohesive exhibition. Furthermore, all the shortlisted artists’ work requires too much background information to decode, which alienates audiences from the Prize’s mandate to encourage debate about contemporary art. It appears wilfully obscure and uncomfortably impenetrable, which is only exacerbated by the fact that video art demands such an investment of time from the audience.

The reason for this somewhat unfashionable tirade against video art is twofold. First, video unfolds over time, which, combined with our being accustomed to narrative film, leads us to expect or hope for something that often does not occur. The apparent simplicity of the medium betrays audience expectation, which is difficult to accept when you’re being asked for 54 minutes of your time, as Campbell asks with It For Others. The problem, however, is not with video art but with the fact that audiences are not well-versed in how to approach it. There is nothing wrong with ‘difficult’ art, since Picasso, Pollock and Warhol were all thought difficult in their day; indeed, art should be challenging, but there should also be critical help on hand, for even Pollock had Clement Greenberg behind him, trying to make sense of this new thing that was happening to painting. Video art suffers from a lack of popular critical support and is therefore currently inappropriate to the ends of the Turner Prize.

Second, at the risk of sounding like Adorno, video has infiltrated every aspect of our lives as if passively watching the moving image is an acceptable alternative to living real life. The production of the moving image used to be practised by the few who had perfected the craft for the entertainment of the many, whereas now anyone can press record and point the lens, thus washing all the artistry out of the artform, and this applies to a disarming amount of the so-called ‘video art’ we see today. This means that the benchmark for producing good video is very high, not because most video out there is good, but in the sense that the proliferation of video rather makes one want a break from it when one enters an art gallery, and if, therefore, one has to sit through yet more of it, it has to be particularly arresting.

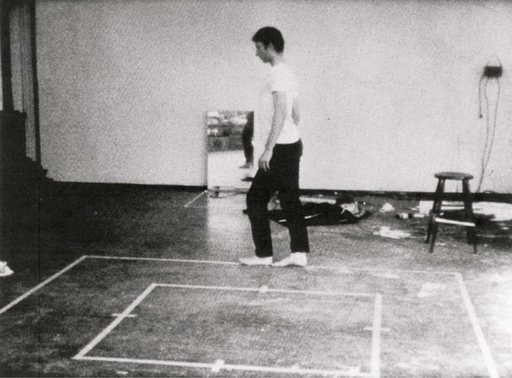

Duncan Campbell’s piece had its charms, but it was too long, insultingly didactic and difficult to follow without a lifetime of scholarship. That said, however, it was beautiful in places, especially the Michael Clark Company history of money dance and the slight at the British Museum raised a nice titter. It is incumbent upon the Turner Prize to explore and promote new developments in British art, but this year felt too early for video, which, like photography before it, has to earn its stripes by differentiating itself artistically from the crowd and gaining a solid critical following. Although there is a lot of video and a lot of talking about it, it is not obvious that its artistic status is beyond question; there is still work to be done here. Back in the 60s when Bruce Nauman filmed himself walking in an exaggerated manner, he did not have YouTube to compete with, so the artistic status of the work went unquestioned.

Bruce Nauman, Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square, 1967

That golden age has passed and art has to work harder to justify those things that want to be artworks but are indistinguishable from things that are not artworks. As Danto says, it is up to the artworld to make this difference apparent, and often with video art the difference between that and a arthouse cinema is not clearly delineated (look, for instance, at Runa Islam who effortlessly manages this distinction). Art might have entered its post-histotrical, anything goes phase, but it must still bear a mark of distinction if it is going to be worthy of inclusion in an art prize, for one would be laughed out of town if one took a painting to Cannes and entered it for the Palm d’Or, although that might just be James Franco’s next stunt.

The video-heavy exhibition this year felt more like a chore than anything else. Sitting through yet more moving images in the vain hope that there might be a point or a thrill or a lol did nothing to distinguish the distinctive experience of art from the mundane experience of everyday life. It just felt like a protracted and ticketed version of scrolling through Facebook – wanton exhibitionism, pretentious rambling and iconoclastic eulogisers for a lost moment. But then we should not expect anything else from a contemporary art prize that used be exciting but has in the last decade gone down with a dull thud. A prize, no less, that George Shaw, Nathan Coley and Dexter Dalwood did not win, so one wonders if we should trust its judgments and proclamations anyway.

Words: Daniel Barnes