Maggi Hambling, in front of her Walls of Water Paintings at the National Gallery

Ever since Tracey Emin said that it is impossible for a woman to have children and be a great artist, female artists have received attention in the male-dominated artworld. In the wake of Emin’s spectacular show at White Cube, Georgia O’Keeffe has set an auction record and Maggi Hambling has opened a masterful exhibition at the National Gallery. Sometimes we have to accept that Difference only exists because we have constructed it, and sometimes we have to deconstruct it.

At the core of Emin’s rhetoric is the disarming notion that female artists are treated differently from their male counterparts in terms of critical reception, sale prices and press attention. This is predicated on the contradictory idea that, on the one hand, as child-bearers women are inherently different from men, but that on the other hand, they should nonetheless be compared to men as if discerning what is distinctly female in their work will help us to understand it.

It is one thing that men and women have different experiences of the world, which is the subject or conceptual content of their art, but it is quite another that these experiences are treated in such radically different ways. Aside from the manifold socio-political ramifications of a division between the sexes more broadly, in art it creates value. Since works of art have no inherent economic value as objects, it has to be imposed on them by reference to categories which distinguish a given work or group of works from others. The category of female artists has, on the one hand, the logical extension that it does not include men, but on the other hand, it has an ideological extension whereby it encapsulates works which are ‘distinctly feminine. This is treated as a category of Otherness, as an exception to the rule that creates value. It is testament to the smooth operation of Zizek’s big Other that we hardly notice this: the thick symbolic texture of prejudices and expectations that fills the gaps in our everyday perception leads us to accept the category of female artists as an expression of conceptual, aesthetic and economic Difference within the artworld.

The category of female artists can command high value: female artists are treated as a minority so the internal value structure is geared towards making the most of that artificially constructed scarcity. Nonetheless, these prices are still less than those of male artists, even for comparable artworks. It is a curiosity of the market that male and female are of such different kinds that prices reflect what is thought to be a primordial Difference, as if it is parallel to the market value of oil compared with pharmaceuticals. Thus a work by a female artist is valuable because there are relatively few of that kind and quality, but the same work by a male would be worth less in virtue of its comparative abundance. Tracey Emin’s My Bed went to auction with a high estimate of £1.2million and sold for £2.5million; for a male artist of comparable standing, with an equally seminal work, you would have to double the estimate and triple the selling price.

So it was quite an event last week when Georgia O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1 (1932) sold for $44.4million (£28million) at Sotheby’s New York. This nearly tripled its high estimate of $15million and astronomically surpassed Joan Mitchell’s record, set in May this year at Christie’s, of $11.9million for a female artist. As ever, the numbers are ludicrous, but more ludicrous is the fact that in the 21st Century we are still entertaining the notion of a ‘record for a female artist’ on the basis of the mystifying fact that these figures really are unusual for works by women when they are commonplace for men.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1

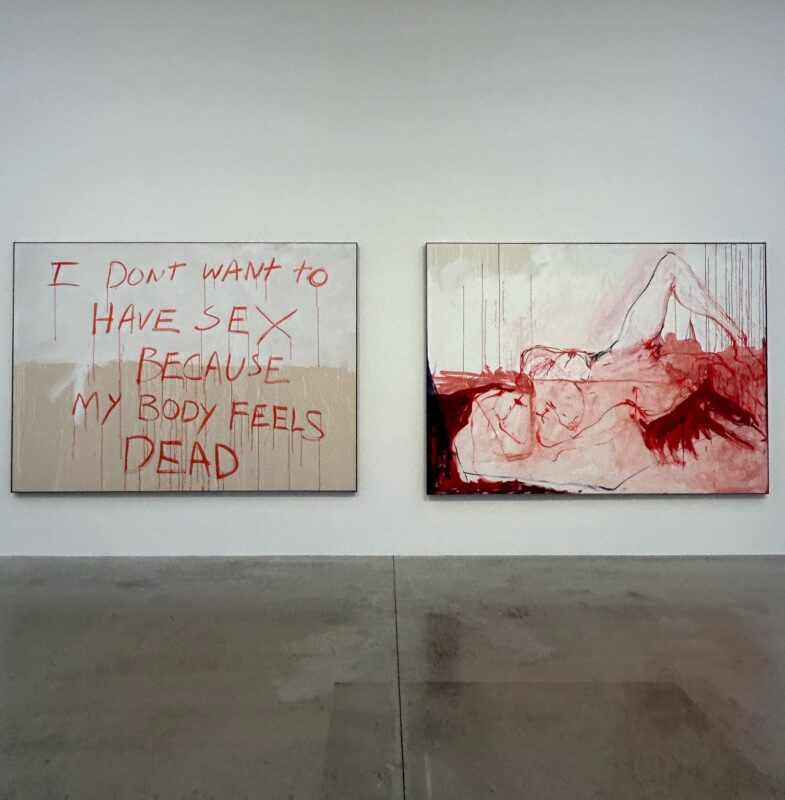

On some level we all know this difference should not exist; we all know that artworks are – in the parlance of Derrida – orphaned at birth and have to be judged in isolation from the sex or gender of the person who created them. The difference in value is constructed by the market, but the real problem is that this both feeds into and stems from a sense that there is a real aesthetic difference between the work of men and women. This is a generalisation based on some uninteresting biological facts, which fixates on a few artistic differences and glosses over a billion similarities. Emin’s work gains its distinctly ‘feminine’ character from its subject-matter – abortion, the female body and abuse by men – but this is a particular case, compared with Etel Adnan, who showed alongside Emin at White Cube, who displays no such easily pigeonholed characteristics.

The greatest contemporary example of how the idea that male and female are useful categories for thinking about the value of art is a perverse construction is Maggi Hambling, who is currently showing her Walls of Water series at the National Gallery, London. These are heartbreakingly beautiful paintings whose energy and sharp perception of nature owes more to Turner and the sheer talent of their creator’s mind and hand than to anything that might – even fleetingly – be construed as a gendered difference. If you shut out the noise from your background knowledge and prejudices, there is nothing in these paintings to make you draw any conclusions about whether they are made by a man or a woman, and therefore there is nothing that could lead you to make a judgement of value on that basis.

There are plenty of interesting differences between human beings, which is the very lifeblood of art, but this has nothing to do with gender. This is not to deny individuals the right to celebrate gender differences as they see fit, but it is to absolutely deny people the right to impose such a difference upon others. The fact that two people make different art is a function of their personalities, talents and histories rather than a directly tangible result of their being a man or a woman. Sometimes men and women will make art about their experiences as such, but the concept of gender, which treats ‘female artist’ as if it is a useful category is artificially constructed.

Emin’s point was that the value structure is so divergent that women have to work harder to gain the recognition that men receive, which is a result of this notion of Difference between the sexes that we have constructed. While it might be a relevant difference for some purposes, it is difficult to believe that it is relevant to the value of art. It is even more difficult to believe that the artworld clings so tight to an archaic distinction that would scarcely be tolerated in other fields.

Words: Daniel Barnes