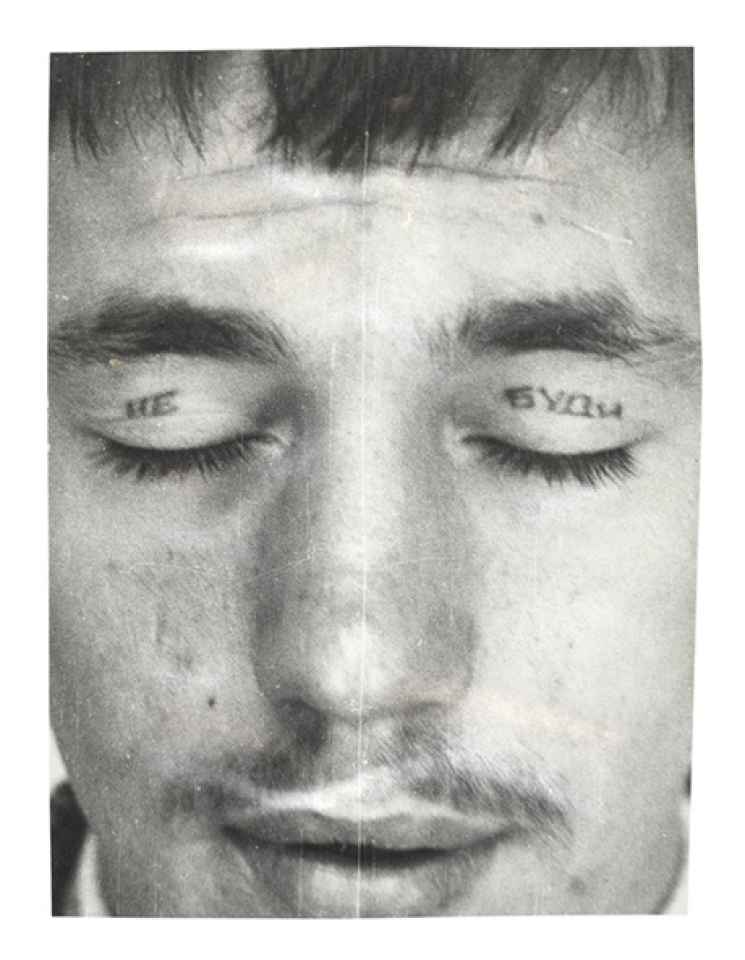

When does documentary photography become art? Only, perhaps, when the primary effect is down to why the subject is chosen and the way it’s depicted rather than what the subject is – see, say, Ghirri, Egglestone, Sugimoto and Ruff, to nominate some favourites. But there’s considerable power in the straightforward presentation of the right subject ‘unimpeded by artistry’, to quote Grimaldi Gavin’s press release for 23 photographs from Arkady Bronnikov’s Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files (to 22 Nov). They show the extensive markings on prisoners in the in the 1960’s – 80’s, typically made crudely with an adapted electric shaver. They were recorded purely to facilitate police recognition of criminals, but now, with the extensive commentaries provided, they reveal the oppositional personalities and unofficial histories of a separate world. A knife tattooed as if through the neck indicates that the man has murdered another prisoner. Churches are presented not for religious reasons but to flag a refusal to conform to the state system: each cupola indicates a conviction – here six for burgling houses (as indicated by the cat). And how were those eyelids made to say DO NOT / WAKE? By inserting a metal spoon under the lids so that the needle didn’t pierce the eyes. Tattoo culture is now much more mainstream (and has been offered by artists such as the Chapmans), and Russian prison tattoos themselves are widely known – but this is still a fascinating exhibition of almost art.

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?