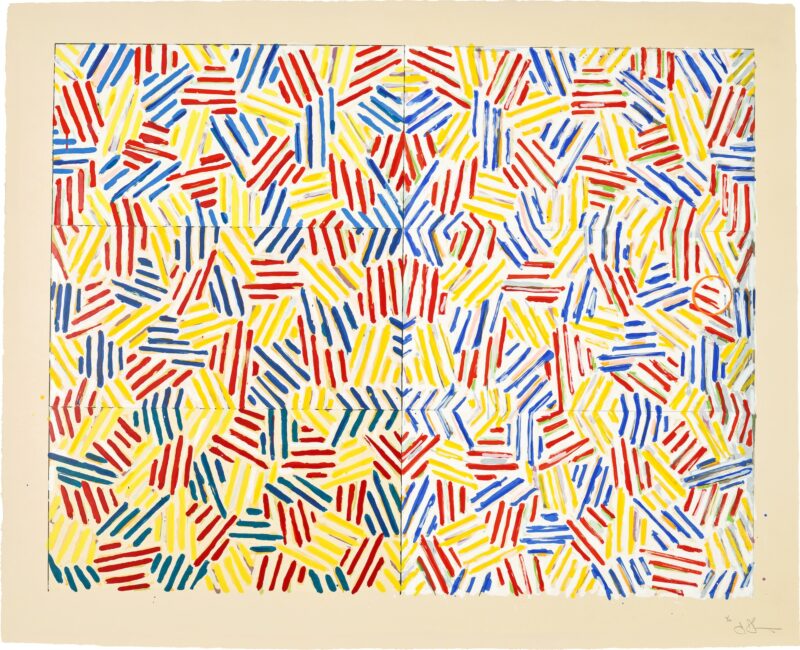

Stanley Casselman making one of his fake Richters

In November 2011, Jerry Saltz announced on his Facebook page that he would pay anyone $155 to make him a fake Richter, Ryman, Flavin, Fontana, Duchamp, Hirst, Guyton, or Agnes Martin. A year later, he ended up with a Richter by Stanley Casselman. This tells us a great deal about the price of contemporary art, but it also raises questions about value in cases where an aesthetic difference cannot be discerned.

Richter’s current auction record is $37million, set at Sotheby’s New York in May 2013, for a photo-realist painting of Milan’s Piazza del Duomo, Domplatz, Mailand (1968). At the time of Saltz’s challenge, Richter was the subject of a major Tate Modern retrospective and his prices had reached $16.6million at auction.

It is baffling to think that prices more than doubled in less than two years; Saltz, like everyone else, watched in disbelief as blue-chip prices rocketed. It now looks like a bargain that Abstraktes Bild 724-1 (1990) sold last week at Christie’s London for £1,874,500.

But that is still too much for Saltz, who named a price that is completely rational: it is not so much that it appeals to those with more money than sense; but nor is it so little that it suggests the commodity is worthless or that practically anyone would pay it on a whim. $155 is an amount that many people could afford to spend on something they really wanted, but would nonetheless have to consider very carefully. As such, it cleaves apart symbolic value and market value as reflections of the artwork’s inherent worth. Instead, it illustrates that the price of art is a function of what someone will pay for it, but instead of locating this in the billionaire who will pay a crazy price because they can afford it, it locates it in the person who desperately desires something and will pay at the top end of their rational capabilities.

Saltz calculated how much he could afford for something that aesthetically resembled a Richter as closely as someone who is not Gerhard Richter could manage. Walking around Marian Goodman’s swish new London gallery, which Richter boldly inaugurates with over 40 recent abstract paintings, it is not difficult to see why. The uniform enamel of the Doppelgrau paintings, pictures of nothing but their glass surfaces reflecting back the entire world, are lessons in seduction in fifty shades of grey. The swirling, bleeding colours of the Flow paintings conjure the chaos of light when you close your eyes while staring into the sun, and yet the glass surface causes the entire abstraction to recede into an otherworldly dimension of order that stands simultaneously removed from and just within the grasp coherence. The one oil on canvas work in the show, Abstraktes Bild 875-3 (2001), sings a muted song of representation, buried beneath layers of paint which seem chiselled away in order to reveal something urgent but ultimately lost beneath.

Abstraktes Bild 2001 52 cm x 47 cm Catalogue Raisonné: 875-3 Oil on canvas

Richter is a modern master, so one wonders why anyone would want anything but the real thing. And here we get to the crux of the issue: ‘the real thing’ holds a lot of sway, for both collectors and casual viewers, because people care about authenticity. Authenticity has two senses here: first, that it is what it appears or purports to be; and second, that it is the product of some particular hand. Saltz is careful to maintain the first sense, prescribing that he does not want an outright forgery, but rather something that has the appearance of Richter made by someone else.

But, appealing to the second sense, no matter how perfect a simulation of a Richter it may be, it is missing the crucial authority of Richter’s own hand. The price of contemporary art is a figure put upon the authentic product of an artist, even if this has been diluted into the authentic product of an artist’s studio. In the age of celebrity and the mass art market, authenticity – as the locus of price and the arbiter of value – has been reduced to the brand name an artist has constructed for themselves. Saltz’s painting is therefore an oddity because although it is authentic in the sense that it is precisely what it purports to be, it is inauthentic in the sense that it lacks the right branding.

It is no surprise that the astronomical price of contemporary art reflects an irrational faith in the brand, but Saltz’s wilful imitation of a Richter reveals something infinitely more interesting. In focusing on the brand as an indicator of market value, the price of art has become utterly divorced from symbolic value, which is a judgement of the value of the work as an aesthetic object that a human being engages with and gains a certain worthwhile experience from. Saltz, unlike wealthy collectors, has been able to disavow himself of the brand precisely because he is interested in aesthetic affect.

Saltz knew it was unlikely that he would get a perfect fake, but he wanted something as close as he could get. Casselman showed him over fifty canvases, most of which he rejected as too pretty, too deliberate or too self-conscious, but the two that made Saltz’s heart skip a beat were the ones that Casselman himself rejected as mistakes. Here Saltz saw the Richterian appropriation of accident, as if Casselman – a very gifted and accomplished painter – could only make a Richter when he was not concentrating.

Casselman signed his own name on the back of the two canvases and received his fee. Saltz walked away with an affordable artwork which replicates the aesthetic experience of an unaffordable artwork. He was able to achieve this because he rightly doubted that market prices reflect what is important about art. There is no doubt that Richter is a great artist, but it is a matter of mere historical contingency that he has branded a certain range of aesthetic objects. The fact that there is no discernible aesthetic difference between a Casselman-Richter and Richter-Richter indicates that the artist’s skill as a craftsperson trumps the brand every time when the goal is a certain kind of aesthetic experience. The proof of the pudding is not, as they say, in Gordon Ramsey’s ineffable spirit, but in the eating.

Casselman was able to make a near-perfect Richter because art is just stuff made by people for other people to experience and to enjoy, and what difference does it really make if it is experienced and enjoyed just the same as its indiscernible counterpart? Casselman could, as Saltz points out, become very rich indeed if he took his Richterian talents seriously, but as an artist he would rather build his own brand than franchise someone else’s. After all, art is about doing what you want and creating aesthetic objects for people to enjoy forever, for Richter or poorer.

Words: Daniel Barnes