You do an awfully good impression of yourself. That’s the first line of Bret Easton Ellis’ Lunar Park, and what I was thinking as I was pretending to listen to the aggressive hard sell of an artist from some prize or other as she press-ganged me in to giving her my business card. I was trying to work, and I was hungover and distracted, and unwilling to engage with somebody who didn’t even know that I am nobody. That’s the way it is at Frieze – people talk and talk without even knowing who they’re talking to. You get a real sense of desperation in their tone as you glaze over and drift into an abyss.

But now the end of Frieze is upon us. There will be a collective sigh of relief all round, even from those whose week has made them several million richer. Both the people and the fair were looking tattered and frayed, after the hard graft of look look look, buy buy buy, sell sell sell, party party party.

I languidly dropped by White Cube to have one last look at those fish – Damien Hirst’s I Want You Because I Can’t Have You (1993). Regardless of what he did after that, those fish pieces are some of the most poignant, moving works of his generation: their cold stillness, lives petrified in clear liquid, forever in stasis and yet in a state of pure transition, takes on a new significance today. The fair is at its end, all the art will be dispersed and remain as it is forever, unchanged, unmoved by this event that has obsessed us for so many days.

Wilkinson [G1] had some very odd Derek Jarman paintings – visceral, lumpy molluscs of black paint with broken glass, seeds and He-Man figures embedded in them. It casts a dark shadow over Jarman’s artistic reputation, as if his career had been hijacked by a petulant child or by Oscar Murillo. I’m sure the name sells them, but then Frieze too often trades on names to justify so much that isn’t very good.

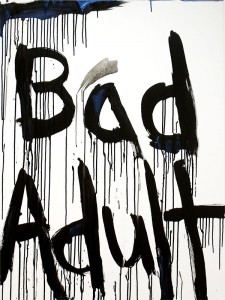

I could not suppress a titter every time I passed by the 303 booth [E5], catching sight of Kim Gordon’s Bad Adult painting, as if every time it was talking to me, knowing what I did last night or last summer. Everything – as it always had been – was all about me, as Bret says. It’s a wonderful thing when a work of art delights every time and makes a direct connection with the viewer. That is what was so great about Hauser & Wirth – it spoke to the people as arbiters of taste, style and culture, rather than just to collectors as cash cows.

Frieze has made a great effort to take art more seriously, not least in the Projects and Live programme. The galleries, in particular, have made a concerted effort to look less like popup showrooms – with gimmicky results like tea rooms, playgrounds, nail bars and cyber cafes – but it really felt like an attempt to change the character of the fair. But any such self-conscious acknowledgement of the fact that there is enough spectacle and money already inevitably turns back on itself by generating yet more spectacle and money.

It has been refreshing to see the bling subdued and the rampant capitalism shielded by a sincere attempt to make the fair accessible to people who just want to see cutting edge contemporary art. The net result is that the fair has felt more like a spectator’s event than ever – the buying and selling has taken a back seat to the carefully orchestrated theatrics that are there to entertain those who are just looking and absorbing. Like any amazing trip, it felt exhilarating and important at the time, but in the end we were just bad adults drinking too much and filling our greedy eyes with luxury goods from the artworld’s Ikea catalogue. It was great fun, not to mention occasionally edifying. Now it is time to pack up the tent and get back to real life. Real life sucks, but Frieze is a delicious fantasy that we get to live once a year, and I adore every ludicrous second of it. And then you have to call your mother, and say, ‘mother, I can never come home again because I seem to have left an important part of my brain somewhere in Regent’s Park’.

Words: Daniel Barnes