On the night of the Scottish referendum, Martin Creed and I were in my hometown on the Isle of Wight, at the closing party of his Tate Artist Rooms on Tour at the Quay Arts Centre. Creed was playing guitar and talking about his work, I was playing homecoming queen and talking about his work. It was a magical evening. Creed said that although he ‘makes about as much money as a train driver’, he’d rather be in the studio than in meetings all the time. I talked about how Creed’s work is pure expressionism, masterfully dressed in the aesthetic of minimalism and conceptual art. But then I got to thinking about how train drivers make money from something tangible, while Creed makes money from producing artworks which consist of almost nothing at all.

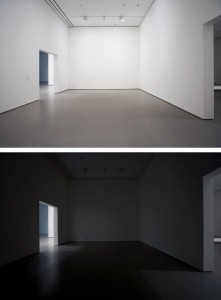

A few years ago, I wrote that Creed’s Turner Prize winning Work No. 227 The lights going on and off (2001) was the first great artwork of the twenty-first century. I thought this – and still do – because at first glance, it looks like the sort of art that enrages the Daily Mail, but in reality it is precisely the kind of art we desire: simple, elegant, rich and expressive of all that occupies the human condition. A work of art should lead you to have some kind of insight that nothing else could generate and The lights going on and off excites that feeling so economically, it’s such a simple thing and yet it’s very powerful.

The movement between dark and light creates a rapidly fluctuating sense of panic and relief, loneliness and comfort, confusion and clarity that you never quite have time to absorb or understand. It starts off as a surprise, a moment of uncertainty and chance, but then settles into a rhythm. The result is that it makes you think about how life – and the universe – is so fragile, so delicate and ultimately just a series of seemingly random flickers that are generated by a preordained force that you can neither control nor access. You walk away from this work considering the fragility and fortuity of your very existence as a series of unstoppable on/off movements that constantly catapult you between the positive and the negative.

This is art which offers a plethora of things to see and yet always dissolves into an idea in the mind of the viewer, simultaneously affirming and denying the entire world by the very fact it has human expression at its core, which is why Creed’s art is neither minimal nor conceptual. It is like minimalism with a shock of colour and conceptual art with an injection of emotion. Furthermore, if it were minimal or conceptual it would be easy to explain how Creed makes a living – people love to buy and own objects, even ones that consist of very little substance or have ideas as their overarching content. But Creed is selling something altogether more ineffable and more existentially vital.

It looks like minimalism because there is nothing there but flickering lights, so you think there is nothing other than the pure aesthetic experience. And it looks like conceptual art because you think these flickering lights is a work of art so there has to be a meaning hidden behind the object, an idea which is the real meaning of the work, rending the object largely irrelevant. In minimalism, the work of art is just what it is and nothing more, like Donald Judd’s boxes are just boxes hung on the wall; the artwork is all about the aesthetic experiences of the object. In conceptual art, the work of art is not what it is, but is in fact something more, namely an idea which the object only suggests or inspires, like Damien Hirst’s shark, which is an exploration of the fear of death rather than a mere zoological specimen.

Creed’s trick is to maintain that the object is just what it is, but to insist that it could also be more or less than what it is, leaving all possibilities open and dictating nothing, so that, despite appearances, it is not minimal or conceptual at all. It really is just the lights going on and off in an empty room, and then there is a gap where it is less or more than that, and the gap has to be closed by the viewer’s emotional response. That response is always a struggle between opposites, aptly illustrated by Work No. 200 Half the air in a given space (1998) where a sea of balloons falters between a claustrophobic threat and childish delight. Even the most minimal works, like the lights, force you to navigate your way through your fury at the idea that this is a work of art and your sense that it is an act of unbridled genius.

Creed is a great expressionist because he uses such simple means to evoke and provoke strong emotional responses. He presents you with an idea, a thesis, and its opposite, an antithesis, which are both embedded in the work but entirely plain to see – since there is nothing more there than the object itself– but then he invites you make something out of these ambiguous opposites, a synthesis. This synthesis is your emotional response, and your emotional response is the meaning of the artwork, which is quite a different result and process from both minimal and conceptual art.

The joke about playing all the right notes but not necessarily in the right order is the perfect analogy for Creed’s work: something that teeters on the cusp of failure and uncertainty ends in a meticulously executed gesture of artistic dissonance. It succeeds precisely in virtue of the fact that it eschews the high-mindedness of art as something complicated or out of the ordinary, while effortlessly achieving the prized artistic goal of engaging emotionally with the viewer, effortlessly leading to a great insight.

This is the real business of art, and as such it does not have a price, but Creed manages to make a living from it because his collectors are paying for experiences that have humanity as their sole semantic content. This is the perfect expression of Isabelle Graw’s injunction that the art market must put a price on pricelessness: insofar as art is an exchange commodity, it must have a price attached to it, but the price is being attached to the priceless symbolic value of art as an edification of the human spirit. Creed has struck gold – as least as much as a train driver – because he makes the kind of art we really want once we shut out the noise from our desire for gold, diamonds and Popeye.

In Creed’s work, the delicate tension between cultural and economic value as a function of the work of art as a cultural object that can be exchanged collapses because the objects are practically worthless, while the experiences they produce are priceless. The value of culture here is entirely divorced from the tangible products of culture that museums preserve and collectors revere. Economic value is here constructed entirely out of symbolic value, which itself is always already negated by the human gravity it carries outside of the market. He does this by making an everyday object mirror our experience of life itself, which is, after all, just about anything and nothing at all.

Words: Daniel Barnes