Anselm Kiefer wants to turn Switzerland into a maritime nation. If only, he thinks, we could discover the mythical universal solvent – the Alkahest – that has preoccupied alchemists for centuries, all the land could be dissolved until Switzerland opened out on to the sea. It sounds like the rambling of a madman, but it is the perfect distillation of an artist whose entire practice is an interweaving of myth with history and alchemy with art.

Kiefer was born in 1945, so unlike his older contemporaries – Baselitz, for instance, who endured the firebombing of Dresden – he never witnessed the war firsthand. This one biographical fact alone accounts for an entire career: Kiefer was thrown into a world of profound mourning, ravaged by a monumental event that changed the course of history, with the weeping wounds and the weight of the conflict between the official and the unofficial narrative. All of this – a vast moment in history – was, for Kiefer, both a tangible fact and an ineffable mystery. It is for this very reason that the line between myth and history dissolves in Kiefer’s work, but is complicated by the fact that Kiefer is toying with German identity, guilt and horror on an industrial scale.

Art, he says, is difficult, not entertainment, as a parallel declaration to his art’s implication that history is not academic, but the structure of human life. A series of early works depict Kiefer performing a Nazi salute: the Heroic Symbols are paintings in oil and water colour that exude an untainted classicism and the Occupations are photographs taken in noteworthy locations around Europe. This is art that is so far from entertainment that it swells into a nightmare or an obscenity, as Kiefer forces Germany to confront the reality of its past that was, at the time, hardly three decades old. The only other people who have maintained such an unflinching, brutal attitude towards that chapter in history are Nazi war criminals and holocaust deniers.

Kiefer’s preoccupation with alchemy and myth underwrite his exploration of these themes, allowing him to draw in references from philosophy, poetry, mysticism, music and religion. This does not decorate the work, it deepens its humanity and urgency by introducing an irrepressible timelessness which illustrates that whatever trials humanity faces now have always persisted at the core of the soul. Alchemy and myth, for Kiefer, represent humanity’s internal conflict between ambition and innovation and fear and ignorance, which has characterised every moment of history. But they also map on to distinct strands of the artworld that Kiefer sits, nearly indestructibly, at the top of.

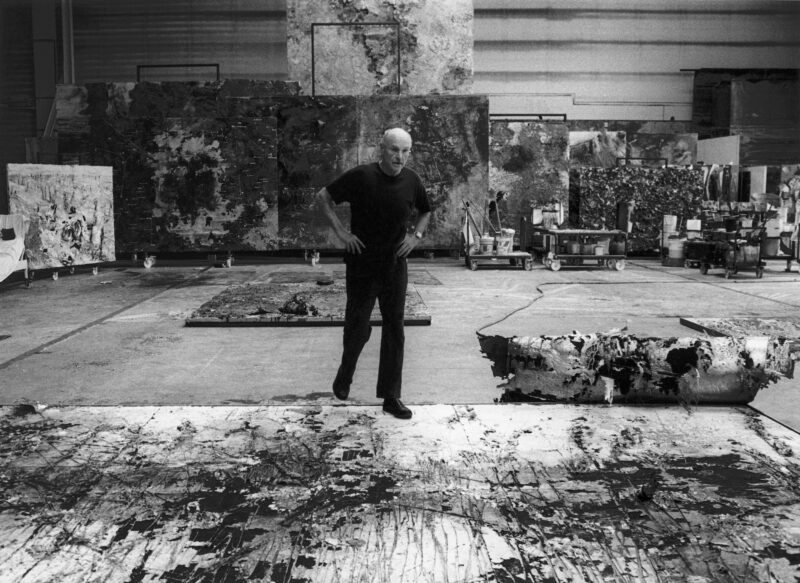

The alchemist’s quest for the philosopher’s stone – the substance that would turn lead into gold – is a persistent theme in Kiefer’s work. He explored this on a monumental scale in a series of works based on Fulcanelli, an obscure figure who claimed to have transformed 100 grams of lead into gold and wrote a book claiming that the architecture of Europe’s great cathedrals contained hidden signs that unlocked this secret. Kiefer recast Albert Speer’s Tempelhof Airport in the role of the cathedral in a series of vast paintings that aligned the Third Reich’s expansionism with the search for the philosopher’s stone. It is often ambiguous whether Kiefer thinks alchemy is a genuine science or a symptom of lunacy, but it is difficult not to see the implication that blue chip artists are always alchemists. In his own case, Kiefer turns crumbling masses of paint, lead, resin and earth into the gold of artworld stardom. Alchemy and art are two sides of the same coin: craft, technique, ambition and luck converge to generate fortunes out of almost nothing at all.

In Kiefer’s work, myth is almost more important than history because while history is about real-world events, myth is about human narratives that have only a contingent relation to reality. By privileging myth, Kiefer can analyse the way history tells stories that are ultimately open-ended and subject to interpretation, emphasising that emotion is as powerful as intellect. Kiefer is obsessed with the Russian Futurist Velimir Khlebnikov, who conducted years of historical research to conclude that a major navel battle occurs every 317 years, precisely because he thinks history gains mythological status the moment it is written. Khlebnikov’s ravings explain the course of history as well as any alternative, since history must always already be the version of events that someone wants to promote, which has the same disregard for Truth and concern for power as any myth. In art, too, myth supersedes any hint of truth, where the market sells stories that incidentally have paintings attached to them; Kiefer’s canvases with fleets of lead submarines attached to them are the by product of a narrative that makes the rich feel enlightened and cultured.

Legend has it that Kiefer’s paintings are sold with a disclaimer to the effect that decay is built into these unwieldy masses so that collectors cannot complain when clumps falls of at even the lightest breeze. Art is only alchemy and myth, but it is also just matter that, like everything else humanity busies itself with, is subject to entropy. The message in the end seems to that, although life, history, humanity and evil seem very important, it all just goes back to dust in the end. That is why Kiefer tells the story with the final authority of Kant’s dying thought: there is nothing more so great and so true as the starry heavens above and the moral law within.

Words: Daniel Barnes