Ahead of Dubai galleries returning from the Summer break, we take advantage of the quiet August period to look back at some of the exhibitions from last season, starting with So Long and Thanks for all the Fish, a group show at Lawrie Shabibi featuring the works of Basim Magdy, Adam Dix, Tanya Makhacheva and Tala Madini.

The cumulative effect of So long and thanks for all the fish is one of alienation. The subject matter is deceptively familiar – technology and marriage rituals – yet here, we are ill-equipped, situated beyond the contextual worlds of each piece without the requisite tools of reference. Late to join already unfurled narratives and unable to orientate ourselves by reference to recognizable symbols; each has been loosed of their prescribed meanings.

Objects and cultural rituals are repurposed – Magdy’s disposable camera snapshots of buildings and the ephemera of the every day become emissaries from a new world order, Makhcheva’s empty wedding venues are haunting spaces where no celebration takes place, Dix’s telephone masts take on shamanistic qualities, and Madini’s innocuous, generic alleyway is the scene of a supernatural transformation and violent attack. The disorientating effect of this alienation-through-contextual-subversion is one of uneasy recognition, giving way to a pervasive absurdity.

Still from A Space of Celebration, Watch the film here

A Space of Celebration passively documents mute, generic ceremonial spaces, empty save for strange, exaggerated and genderless figures. Makhacheva refers to these as “giant deconstructed napkins” and they are lost in the flatness of each scene, located in void spaces that are nowhere and everywhere, cultureless venues representative of all and no traditions simultaneously.

In an interview with Art Asia Pacific, Makhacheva praises her forebears for their “humorous criticality to everyday life, and how they helped society to change itself and maybe look at itself”. To the same end, through viewing her work, we become a non-participatory outsider beyond the ritual, granted the vantage from which to recognise its absurdity.

A dynamic subversion through observation is performed within A Space of Celebration – society’s traditions become strange spectacles and it is we who loose the symbolic from its received meaning.

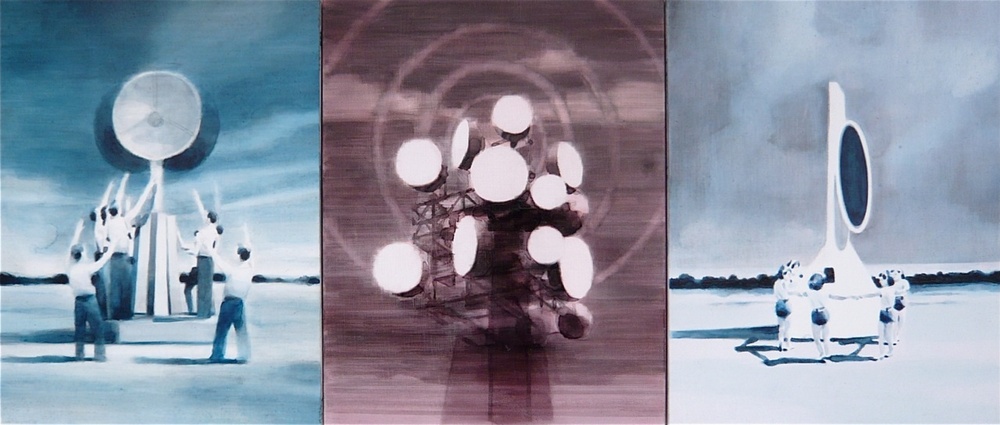

The paintings of Adam Dix are also quasi-familiar, not through any recognition of a lived reality, but rather located on the cusp of nostalgia like a dream or memory beyond the reach of the consciousness. These are folkloric, neo-futurist tableaus where the tropes of technological innovation become totemic deities. On one level, the scenes are an obvious reference to our relationship with technology and communication, but more than this they gesture towards the mythos that underlies this obsession.

Through “an ongoing interest in science fiction, and old b-movies from the 1950s” Dix came to understand that “the way we live now owes a lot to the psyche and the advances made by people at that time”. The paintings demonstrate how our relationship to technology is not our own, but is psychologically dictated by the past and, through the re-appropriation of technological ciphers – the telephone mast as the conducive totemic deity, the satellite dish as tribal costume – functionality becomes secondary to invested meaning.

As a whole, Dix deals with “communication technology and our desire to communicate” and, like the destabilised meanings of Makhacheva’s celebratory traditions – here technology becomes the overreacher – our desire to communicate thwarted by that which ought to aid it.

The almost-nostalgic tone of the paintings stems from a preoccupation with mid-century paraphernalia, the palette drawn from “a lifelong obsession with collecting old printed material from then: science-fiction books, vintage LIFEmagazines, National Geographic and comics” (Inventory Magazine). These fragments are assembled to forge a new perspective on our present, through a reimagining of what could be a not too distant future, or a recent past replayed in memory.

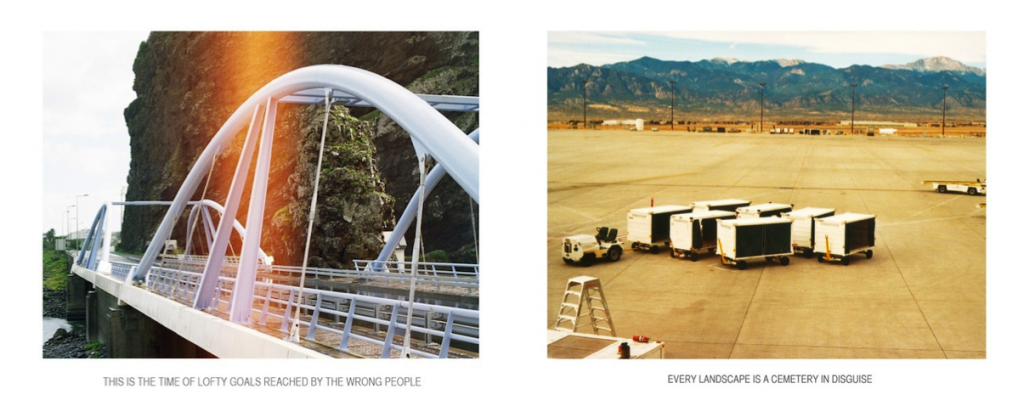

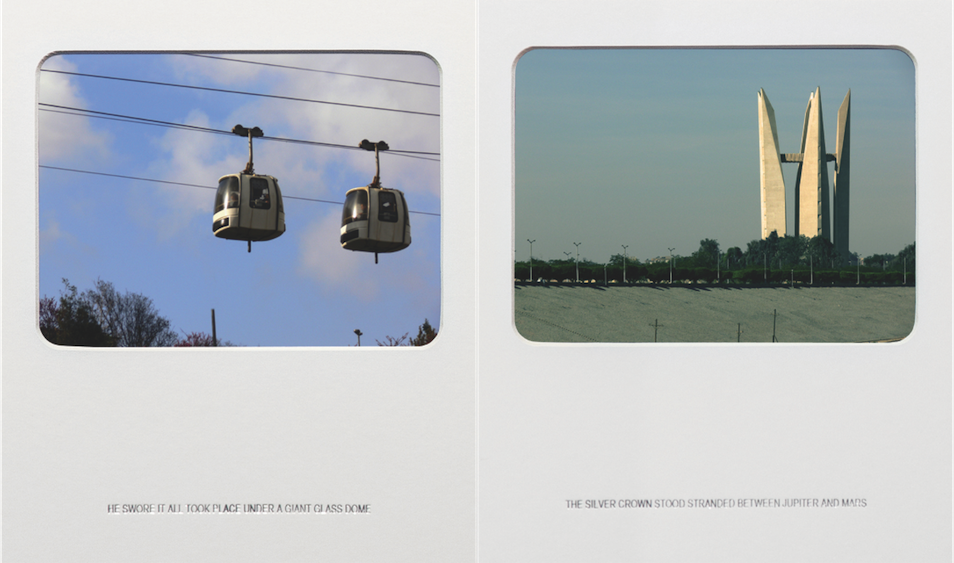

The decontextualized fragments of Basim Magdy’s Every Subtle Gesture become loaded with meaning through juxtaposition. Snapshots and isolated descriptive sentences evolve into glimpses of a narrative and are granted a value beyond the sum of their constituent parts.

These pieces came about when Magdy was thrust into a new world order of Egypt’s revolution, unable to work otherwise, the snapshots were instilled with new meaning and purpose. Magdy explained to Art Forum the genesis of the work; “a personal collection of photographs that I have been taking since 1998, many of which I never intended to show. But almost six months after the revolution in Egypt—its utopian vision becoming a tangled web of confusion—it was impossible for me to work again or do anything apart from following the news… In my mind, the entire series constructs a loose narrative based on a group of people who keep trying to succeed but continually fail” – as told to Stephanie Bailey, Art Forum 2013.

The subtle gesture is the desire to create new meanings, to forge a coherent narrative. Yet the process is precarious – alone, these images are unremarkable and the sentences, though each possess a certain poetic elegance, say nothing. Paired up and evolved into a series, the shadow of a structure appears to emerge, as if the artist reveals something pre-existent, an intervention of interpretation impossible within his own context – the tangled web of the revolutionary utopia. The viewer is also compelled to follow this hinted-at thread – each piece becomes a stepping-stone in the story we spin – from nothing to narrative. This act is indicative of our desire to trace rational, causality in everything, following every subtle gesture towards meaning.

So Long and thanks for all the fish demonstrates how we guard against the chaos of haphazard meaninglessness. The process of de-contextualisation unpicks the sometimes grand – love, marriage, religion, sometimes prosaic – telephones, garden ornaments – societal mythologies we structure our lives and our selves around. In the subversive gaze of these artists, the symbolism writ-big of the white wedding dress or a phone mast, become too inflated with a larger than life significance and collapse into absurdity.

The exhibition takes its name from the cult sci-fi classic, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a novel that tells us the meaning of life is the number 42. It might as well be, it’s no more or less absurd than the wedding dress, the telephone mast or the garden ornament.