Damien Hirst has commanded the destruction of an early Spot Painting after his company, Science Ltd, has become embroiled in a protracted dispute over the right to sell the site-specific work. Rather than a tale of greed and wickedness, this is a story which confirms the artist’s authority as creator, which is the final arbiter of value, even for art in the age of minimum wage of reproduction.

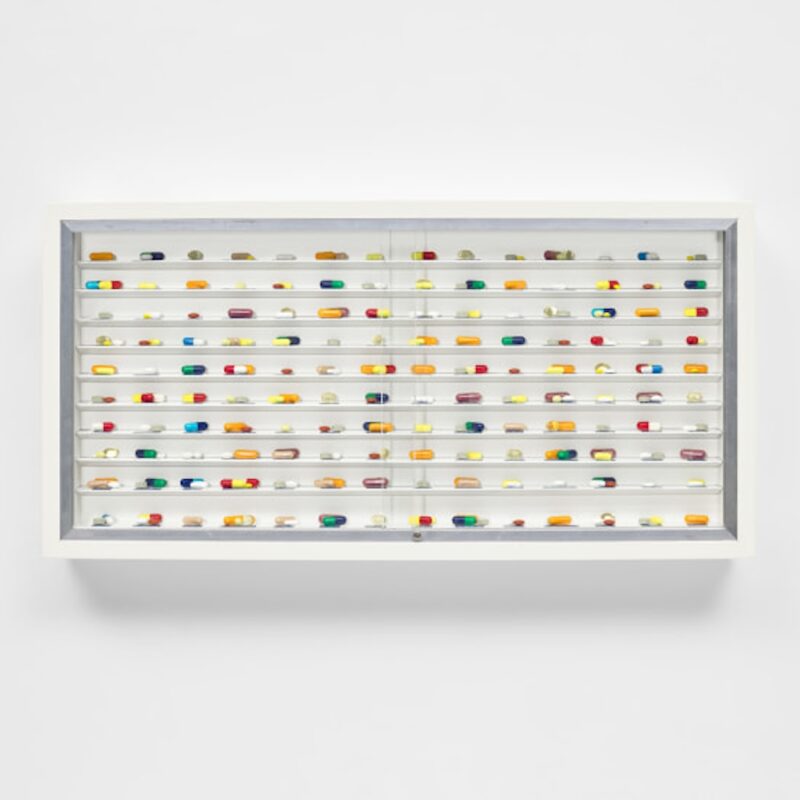

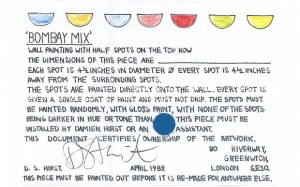

The Spot Painting, Bombay Mix, was painted directly onto the wallpaper in the backroom of a house in Fulham in 1989 as a birthday gift to Jamie Ritblat from his parents. When Jess and Roger Simpson bought the house in 2005 they thought they had inherited an important slice of art history. Spying an opportunity to make a few hundred thousand, they had the painting professionally removed, mounted on an aluminium backing board and framed. The cruel twist here is that in the interim Ritblat had returned to Science the certificate of authenticity and exchanged it for a work on canvas.

The Simpsons were unprepared for a blunt collision with the complexities of the artworld. According to standard procedure, the owner of a site-specific work is the holder of the certificate, so the Simpsons have no claim of ownership and therefore no right to sell it. Science first asked for the piece to be returned and later requested that it be destroyed, since, they claim, the object is utterly worthless without the certificate. The Simpsons, who profess no affection for Hirst and little interest in art, were understandably baffled by this: they wondered why Science would want to destroy this artwork and why were not able to sell it.

The complexity here lies in two areas, both of which have profound emotional resonance, but neither of which offers a solution to this peculiarly aesthetic problem. First, there is a historical case which suggests that the work must remain in situ and nobody has the right to sell it. Empire’s court jester, BBC Arts Editor Will Gompertz, points out that, since the wall paintings series of Spots are amongst the earliest, their cultural significance is in their position in a narrative that has defined a generation; moreover, they are considerably rarer than their brethren on canvas. This artwork is a product of its time and all of its meaning and value resides in its being there on that wall, just as it was painted at some distant time before anybody had dreamed of a diamond skull.

The second point derives from the old adage that possession is nine tenths of the law. On this view, it is easy to sympathise with the Simpsons’ view that the painting is rightfully their property to dispose of as they wish. They legitimately acquired it in the purchase of their house, which was sold according to certain contractual conditions that did not exclude the right to claim ownership over internal walls. But it seems Science’s view derives from Robert Nozick, who said, ‘justice in holdings is historical; it depends upon what actually has happened’. This means that the right to possession depends upon a factual examination of a sequence of events, so that, although the Simpsons justly acquired the property, a certain other – historically prior – contract dictates that Science, possessor of the all-important certificate, is the rightful owner.

On the one hand, although it would be nice to keep the painting on the wall, site-specific works such as this have an ephemeral nature; the important thing is that we can situate it in the endless story of the Spot Paintings, so nothing – historically speaking – hangs upon its actually being there for ever. On the other hand, arguments about possession are thwarted by an ontological conundrum: the object is worthless without the certificate, which suggests that the work of art is something other than the object, so that which is to be possessed is something else entirely. The discussions about history and possession miss the mark by a wide margin: it is not about tangible things at all, but is rather about ideas, for the valuable thing here is the idea of the Spot Painting that the certificate instantiates.

Insofar as it is about ideas, then, this is a dispute about the right of the artist to be identified as the creative authority behind the work. As such, Hirst is absolutely right to demand its destruction. If the work is to be treated as a mere commodity that can be exchanged for cash at whim, then it loses all meaning as a historically situated work of conceptual art. And if Hirst has no control over his work – both its physical being and intellectual content – then he is less an artist than a mere draughtsman. Of course, you favour this conclusion, but it is completely wrong and grotesquely cynical. This is not about the status or fate of a painting at all; it is about who has the requisite authority over an idea, which has contingently been instantiated as both a commodity and a work of art, but which has no necessary connection to either. And whilst everyone can have a say about an object, there’s only one person who can make proclamations about an idea.

Legend has it that legions of assistants make Butterfly Paintings by randomly sprinkling dead butterflies over glossed canvases, so that Hirst can drop by occasionally to decree which are the good and right ones. As a conceptual artist, he is the architect of ideas, and only he knows whether that butterfly is in the right place; similarly, the Spot Paintings are conceptual works whose realisation is pure unadulterated contingency, so their meaning resides in the foundational idea. Bombay Mix is more than just marks on a wall or a commodity to sell; its real value resides in the fact that it is an instantiation of an idea in the mind of someone living. That living person has a duty to the integrity of his art by ensuring that it does not deviate from his ideas.

The consequence of this is that Hirst gets to decide the fate of the work as idea, no matter how infinitely repeatable by assistants and economically disposable it may seem. Despite all the money and the diamonds, Hirst is in the business of ideas and of manufacturing wonder. In commanding its destruction, he is not depriving the Simpsons of the right to their property or wilfully obliterating a piece of art history. He is ensuring that the work of art that he created is and eternally remains precisely the work of art he created, nothing more or nothing less, lest it should become an inauthentic mere Thing that is orphaned by greed or idiocy. That’s pretty decent and aesthetically astute for the man you love to hate as the dark overlord of capitalism masquerading as culture.

Words: Daniel Barnes