Two people, one artist, making art for all in their tweed suits, dining every day in the same restaurant because they don’t have a kitchen, with no friends and traditional Conservative values. They are incisive sculptors of modern life who live in public view, yet remain a tantalising mystery. The story of Gilbert & George is so often told and so integral to their art that it has the authority of theological orthodoxy, but the glue that holds it all together is a pervasive myth.

It is not by accident that little is known about their early lives. Gilbert Proesch was born in the Dolomites, Italy, in 1943 and George Passmore in Plymouth, Devon, in 1942. Gilbert’s family were the village shoemakers and he showed an early aptitude for art with woodcarving before studying in Austria and Germany. George grew up in Totnes with a single mother and a brother who became an evangelical Christian and briefly worked in Selfridge’s. More detail would soil the immaculate conception of Gilbert & George the Sculptors.

They met on the sculpture course at St Martin’s in 1967. It was love at first sight and George was the only one who could understand Gilbert’s English. St Martin’s, they say, was a grim place that rejected colour, emotions and figuration. They wanted to make art that spoke, free of jargon and fashion, to the restless heart of humanity. And so they constructed a world that has Liverpool Street station as the centre of the universe. The East End of London, they always say, is ‘the most planet earth place’, where an alien could land to find all human life within a hundred metre radius. Their art, against prevailing trends, would paint a portrait of the turbulent ordinariness of humanity and craft the most devotional love letter to London. Having lived for nearly fifty years in the same Huguenot house on Fournier Street, they are practically a mobile tourist attraction, and almost all their art has been made from images of their neighbourhood.

They arrived in Spitalfieds, at a time when the East End was truly spit and grit, penniless and full of passion. The idea of living sculptures emerged from the realisation that the human being is the most artful, complex and beautiful thing. They found fame with The Singing Sculpture, which involved the pair singing along to Flanagan and Allen’s music hall classic ‘Underneath the Arches’ for eight hours a day the Sonnabend Gallery, New York. Then there were the videos, Gordon’s Makes Us Drunk and Bend It, featuring these two curious men in suits drinking gin or dancing erratically. And so the Sculptors became the sculpture, using their bodies and images thereof as their primary material. Every detail of their daily lives was scripted and mechanised, removing all caprice and distraction – friends and kitchens – so that they could make art and always be art.

The pictures for which Gilbert & George are known were born in the early 70s. They used to make enormous, elegant, evocative charcoal drawings of themselves strolling around Hampstead Heath. When Konrad Fischer asked how much he should sell them for, they said £1000 as if nobody would pay that, but a few days later the pictures sold and they had enough money to misbehave for a year. And misbehave they did, but they also made some art. They took blurry black and white photographs of themselves getting drunk, which were then framed and arranged in irregular configurations. These Drinking Sculptures were the start of the Gilbert & George picture, depicting the artists and their vision of a turbulent world that consists of nothing more than sex, money, race and religion.

Gilbert & George’s stroke of genius was that, around 1975, they stopped making all the work that made them famous. Recent history instantly became the stuff of antiquity, discontinued relics that could only be acquired at a premium, such as those charcoal drawings that now sell for £1million. Consequently, they are now Britain’s 8th most expensive living artist, having sold To Her Majesty (1973), a Drinking Sculpture, at Christie’s in 2008 for £2.2million. They thus cemented their artistic reputation by creating a welter of value – in both the cultural and economic sense – which would eternally justify anything else they might do. From that moment on, they set about making pictures, establishing their trademark grid and helping in no small measure to establish photography as a respectable medium.

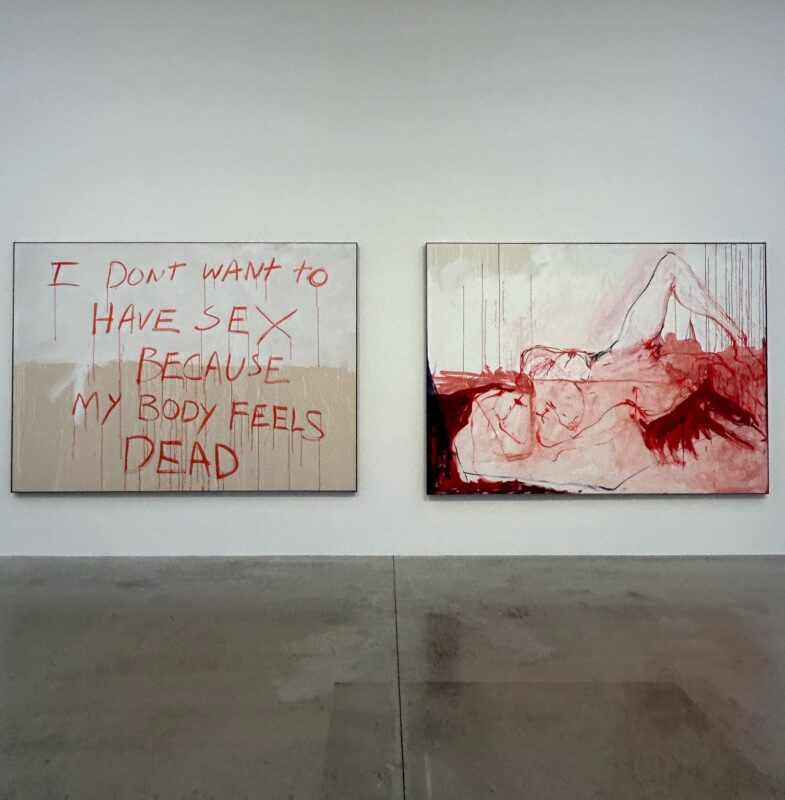

These two well-to-do gentlemen used to court considerable controversy: showing their bums, photographing their excrement and getting skin-heads and Bangladeshis to pose as ‘patriots’. But all the spunk, sweat, piss and class-war made them artworld aristocracy; indeed it is so ubiquitous now that the very idea of controversy is laughable. Once you’ve made Sir Nicholas Serota say ‘spunk’ in public, there’s nowhere else to go. The indivisible remainder of their rebellion is the fact that, against all politically correct strictures, there are hardly any women in a lifetime of pictures populated by archetypal East End boys. The Gilbert & George boys’ club remains a quaint, archaic curiosity.

The remarkable thing is that Gilbert & George’s entire body of work is predicated upon a myth – namely that they are living sculptures all the time. The idea of these impeccably dressed, friendless, kitchenless, monarchists who live and breathe their art to a clockwork schedule is essential to the creation, understanding and appreciation of their art, and yet cannot be indubitably verified as the complete truth. The unbearable lightness of being Gilbert & George is so complete that it is impossible to know what is behind it, as if the real life of Gilbert Proesch and George Passmore is a Kantian noumena veiled by the phenomena of living sculptures. Even their official biographer, Daniel Farson, concluded that what goes on behind closed doors at 12 Fournier Street is very much a mystery.

The myth of Gilbert & George, who are living sculptures through every heartbeat, surely conceals a secret, however banal it might be. But to think that this is disingenuous or empty is to miss the point entirely: the art is the performance of the myth and the pictures are secondary to the men. It is a crowning achievement of Empire that they got the entire artworld to play along, tight-lipped and ecstatic, always hungry for more. The myth dresses the reality of commercial success and artistic achievement in a veil of romanticism that preserves the authenticity of Art for All. Gilbert & George closed the gap between the artist and the artwork one day in 1967 because in that gap there is only ever the inauthentic struggle of an artist who is trying to make art with life constantly getting in the way.

The truth is that it does not matter what, if anything, is behind the myth or whether they ever take a break from being Gilbert & George because they are one of the greatest artworks to have ever been conceived. The myth gives depth and meaning to the pictures, for if the Naked Shit Pictures had been made by anyone else, they would have been vulgar and puerile, but by two perfect gentlemen who live like monks in the shadow of a pious church they are the pinnacle of cosmopolitan social commentary. It is as if Gilbert & George set out to find the truth of human life and discovered that only the objectivity of a living sculpture could grasp the ineffable spirit of human striving. They will take their myth and ultimately their art to the grave, leaving us with only the pictures, as if to say, ‘all my life I give you nothing, and still you ask for more’.

Words: Daniel Barnes

Gilbert & George: Scapegoating Pictures for London is at White Cube Bermondsey from today until 28th September 2014