The death of Miley Cyrus is no laughing matter. They found her body in the California desert. Although nobody really knows what happened, conspiracy theories abound: dark goings on at Disney, the complicity of Billy Ray, a prophecy in a Nick Cave song and, of course, some tenuous connection with James Franco. Only the arid sands of the desert, bathed in the eternal sunshine of LA’s spotless mind, really know.

The rumour is that she was murdered in 2010 by Disney executives because she refused to take part in an orgy. Then she was replaced by a surgically reconstructed fan. The truth is that Miley Cyrus is not dead. The internet rumours are the wholesale realisation of the Baudrillardian nightmare of the precession of the simulacra. But this nightmare is not confined to Hollywood, for it is the standard operating procedure of our very own artworld. It is an obscene excess of what Bret Easton Ellis calls ‘Empire’; that is, the universal complicity of everyone in the entertainment industry in keeping up the illusion of celebrity.

It is the foundational myth of Hollywood: under Empire, everyone plays by the rules in order to conceal the dark underbelly, thus ensuring the functioning of the City of Dreams. So if Disney had murdered Miley Cyrus, a doppelganger would be necessary to continue selling the dream.

The great post-Empire moment, for Ellis, was Charlie Sheen’s very public meltdown when he deliberately got himself fired from Three and a Half Men amid a storm of voracious drug use and casual misogyny. Sheen stopped playing the game that he was paid a fortune to play: he breached the studio’s official line by telling us his show was rubbish and that he was bored to death and mad and, of course, winning; then he committed high treason by treating interviewers as if they had asked him the most idiotic questions imaginable. In Empire, the possibility of entertainment depends upon everyone playing along at any cost. But Sheen blasted the cover off Empire to reveal an aching emptiness, and there is no entertainment in an existential void. Entertainment, like nature, abhors a vacuum and is by extension postmodernism’s primordial lesson in self-loathing.

The art market is the locus of the contemporary artworld’s Empire. It weaves a web of mythology to ensure that we never glimpse the emptiness at the core of art; it perpetuates the distinction between the haves and the have-nots in order to uphold a sense of what is good and right; it demands that we play along by being on trend and holding to an unwritten official secrets act. An essential function of this Empire is to create economic value out of confections of cultural value, thus often spuriously equating the two: Oscar Murillo is good because he is expensive, Jacob Kassay is expensive because he is good, and all the art springs from some welter of unimaginable discontent. It is Empire that tells us that David Shrigley is biting social commentary and that Sarah Morris makes radically different paintings in response to radically different cities. It is the unqualified process of imputing profound creation myths to commercial goods.

This mythologizing can be a lot of fun and it can even be the bedrock of good art; it just goes too far when everything can be excused if it sells and everyone sells who plays along. But the real problem of Empire in art is not its existence as a fact on the ground, since that fact – as I am so quick to point out – is the source of some wonderful art and an endless host of irresistible theatrics. The problem here is specifically that Empire, by its very nature, stifles creativity and art is all about creativity, so Empire obstructs the fundamental nature of art.

But it’s not just the people who are selling art. The ubiquitous Hans Ulrich Obrist, the sturdy Penelope Curtis and the gushing Alistair Sooke – all Empire, trying to convince us of some quasi-Kantian universal agreement that we should be party to. The adorable Ben Lewis is the kind face of Empire, like a sort of artworld Jamie Oliver. Saatchi, professional antagonist and art omnivore, is so Empire that he’s over it already. Brian Sewell is posh and probably thinks Titian was the end of art, but he’s totally post-Empire – he hates everything and likes the Chapman Brothers. But if you want post-Empire – and therefore real critical insight coupled with independent thought – then turn to Waldemar Januzczak or Matthew Collings. Basically, anyone who dares dis the Tate is totally post-Empire.

Hollywood’s post-Empire moment, Bret Easton Ellis argues, broke the deadlock that stifled creative freedom. Ricky Gervais’ hosting of the Golden Globes, Lady Gaga arriving at the Grammy’s in an egg, Kanye West’s ‘Runaway’ and Robert de Niro mocking his own career while accepting a lifetime achievement award – all acts of post-Empire freedom that would have been unthinkable before Sheen. The post-Empire world opens up possibility where before it was closed.

The truth is that art has already had its post-Empire moment, which paradoxically gave rise to the current Empire of the Market. The YBAs were hard drinking party animals who swore a lot and made a bit of art on the side; they wanted to stick it to the Man and take back what Thatcher had so brutally stolen. They rebelled against the stagnant closed circle of the artworld’s crumbling Old Empire of polite criticism and classically trained, intellectually informed artists. Tracey Emin drunk and abusive on Channel 4, Damien Hirst spending his Turner Prize winnings in a single night at the Groucho Club, Marcus Harvey painting Myra with a cast of a child’s hand, Saatchi showing Myra at the Royal Academy, Jake and Dinos desecrating Goya, Sarah Lucas’ sexy kebabs and cucumbers, Gavin Turk failing his degree…and yet all of them making brilliant, fresh, urgent art. All quintessentially post-Empire.

But it backfired and the YBAs created the New Empire. Out of the fuck-you-spirit, they created an industry that we now give the honorific title of ‘contemporary art’; they became the establishment they were so hell-bent on wrecking. What went wrong? It was a unique combination of a desolate Britain and the sense of hope aided and abetted by parallel movements in Britpop and New Labour. This new art, music and politics filled the hole left by recession and Tory rule, and suddenly there was money too, so there was a sudden lust for more and more things to fill the hole. In this climate, art commanded so much money that eventually the New Empire had to be established in order to make an excuse for all this excess.

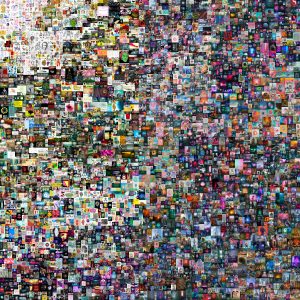

Once the YBAs became establishment and Empire struck back, the market, which is in reality a mere contingency to the existence of art, had gained the status of an absolute necessity, leaving those who fall outside of it hopeless, diminutive and doomed. Now that art has returned to Empire that sense of hope, freedom and rebellion has rotted away; there is a sense that it is impossible to make it big without gallery representation or that you can only make work which the market desires. Consequently content is sacrificed for commodity value and creativity is crushed by demand. The result is that contemporary art is a myth without a foundation, a copy without an original, a market commodity that is an abstraction at heart. It is the death of Miley Cyrus when Miley Cyrus is still very much alive and wrecking.

For all we know Damien Hirst could have died of a drug overdose the night he won the Turner Prize and Empire effortlessly replaced him with a surgically reconstructed doppelganger who bites his lip at Kirsty Wark and orders around the minions just the same. If creativity is to survive Empire, we need to confront the very real possibility that those Spots are painted by Umpa Lumpas and the whole thing is a terrible sham. We need to learn from Charlie Sheen before we end up dumped in the desert for real.

Words: Daniel Barnes