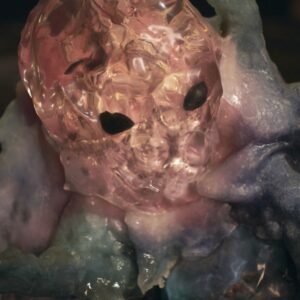

Just beneath the surface of the headlines, there is a crisis brewing. Saatchi is selling Tracey Emin’s iconic My Bed. It is most likely to drift away on a sea of missed opportunities, vanishing into the clutches of a private collector. This immanent and inevitable catastrophe is a lesson in how the unchecked might of the market renders impotent the museums whose mandate is to preserve our rich cultural history.

Contemporary art captures in unequivocal form the spirit of the moment, acting as both barometer and mirror; but it also is an enduring document that tells future generations about a lost past. Often, it takes time for a work of art to be acknowledged as the touchstone of a particular time, but very occasionally history is made instantly, such as when Emin’s bed galvanised the art of an entire movement.

The YBAs struck gold with a relentless project of shock and awe – dead stuff, bullet wounds, elephant dung, stale kebabs, serial killers, sharks and Nazis caused outrage because they were exhilarating spectacles. But Emin went for the shock and bore of the disarmingly ordinary – handwritten letters, drawings, blankets, chairs and unmade beds. The horror was in the sheer banality of the artefacts and the ongoing narrative about her tumultuous emotional life.

As the headlines smoulder and memory fades, the art of the nineties will be typified by That Shark and That Bed precisely because these iconic works crystallised a moment, both entrenched in art history and signalling a new direction. My Bed in particular was a moment at which something changed: the Duchampian readymade lost its clean, almost inhuman surface and became the detritus of a life lived in peril. Suddenly contemporary art was about humanity again, not as an abstract collective, as it is in the work of Hirst or the Chapmans, but as comprised of striving individuals, now elevated to the status of celebrity, but at their core mere struggling mortals. This is precisely the kind of moment in art history that a culture needs to revere and preserve: the moment when the art that was all about spectacle and shock suddenly reveals that beneath the hubris and the glamour there is the bare suffering of human individuals. My Bed works on two levels: it is a self-portrait of Mad Tracey from Margate losing her mind in a Waterloo council flat, and it is an antidote to the glamorous myth of contemporary art.

For the whole of the 90s, Emin – now a millionaire Tory voter – had refused to sell to Saatchi because of his role in Thatcher’s rise to power. But just after the 1999 Turner Prize, which, contrary to popular error, Emin did not win, she agreed to meet Saatchi at a café on Cork Street. Suddenly famous Emin cut a shrewd deal with the revered collector: she agreed sell My Bed to Saatchi, via her New York gallery Lehmann Maupin, for £150,000 only if he also bought a beach hut, titled The Last Thing I Said to You is Don’t Leave Me Here, for £75,000. In September 2000, both works were shown at Saatchi’s Boundary Road gallery.

The beach hut sadly perished in the Great Fire of Momart. The bed, however, was spared the flames because Saatchi had it lovingly installed in a spare bedroom of his Kensington home. He wouldn’t, in true Saatchi style, even lend it to the Hayward for its monumental 2011 Emin retrospective; it has not been seen in the UK since it was at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2008. The fact that he is now selling his most prized possession to fund his gallery, after selling 50 major sculptural works at Christie’s during Frieze last year, suggests that the Saatchi Gallery is in trouble and its reclusive king is getting nervous.

But, for conspiracy theorists who speculate on the Fall of the Kingdom of Saatchi, there is reason to think the storm has been gathering for some time. A few years ago Saatchi offered 200 works from his collection of YBA masterpieces, including the bed, as a gift to the nation. The Tate, that withering bastion of wrongheaded approaches to contemporary cultural history, refused every last one. But Saatchi is an impresario, not a philanthropist, so he was offering the 200 works to the nation in exchange for the Saatchi Gallery gaining museum status, as if he could no longer afford this expensive hobby. It is simply unfathomable why the nation refused to be party to such a pact, and if it all goes wrong at Christie’s on July 1st, then that will go down as one of the greatest, most unforgivable mistakes in art history.

Christie’s estimate for My Bed is £800,000 – £1.2million. It seems a preposterous price for such a seminal, iconic work, but it reflects that Emin’s current secondary market record – for another bed, To Meet My Past, also sold by Saatchi – is £481,875. Whilst £1.2million is peanuts for a billionaire collector, who will happily see the bidding into eight figures if they really want it, it is too much for the nation. And so the market rules supreme: the first time this work ever appears on the open market, it is only within the reach of private collectors. The Tate is going to miss the boat for a second time, but this time the boat is going to crash into an iceberg and is never coming back.

This is a dire state of affairs. The job of museums is to preserve seminal works like this so that a nation can enjoy its history in the flesh, rather than just in the dim pages of histories and memories of lost time. Although the blame lies squarely with the Tate for missing out the first time, it cannot be held responsible this time; now it is due to the disparity between the market and the museum – the fact that private collectors have all the money and therefore wield all the power. To add insult to injury, unless you get down to Christie’s for the presale viewing, you might die having never seen this wonderful work.

There has not been a single suggestion that it has any chance of been saved for the nation; not a glimmer of an effort to avert catastrophe. We can hope that it will be bought by a benevolent collector who will lend it to museums the world over. Or, perhaps, the artworld’s good guy Jay Jopling will buy it, and find an occasion to show it at White Cube, and take tender loving care of it forever. Maybe we should get a million people to each give the Tate £1 to help them acquire it for the nation. But all this is wishful thinking; art goes where the money is, and the money is not in the love of the immediacy of history.

In one of her appliquéd quilts Emin says ‘everything you steal will turn to ash’, and I can’t help but feel the same sentiment applies here. This bed, stolen from the nation by one collector after another, is about to turn to ash because the raging fire of the market will consume it and the state’s museums have no water to put out the fire. It’s as if, accepting their impotence in the face of the market, the museums have convinced themselves that although the roof is on fire they don’t need no water.

Words: Daniel Barnes

Tracey Emin, My Bed, is on view at Christie’s King Street 28 June – 1 July.