Culture has a selective memory because it diminishes the thrill of the Now to admit that we have seen it all before, so when a new celebrity artist turns up the old ones must be usurped. This is what happened to Julian Schnabel: once adored and then sidelined for younger, trendier art stars. Nietzsche had Schnabel in mind when he said, ‘a poet would say that God has placed forgetting as the gatekeeper at the threshold of human dignity’. But on the day that Schnabel opens his first exhibition in London for 15 years, it is time to wonder why we forgot and to remind ourselves to remember.

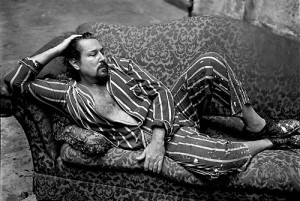

In the 1980s, Schnabel was the prototype Hirst, gaining big money and celebrity status very quickly so that even people who weren’t quite sure what he did knew an anecdote about him. In person, he is a captivating, formidable presence with a mischievous sense of humour that is underpinned by a carefully constructed aloofness. When he speaks he stares into an imaginary horizon, as if waiting for the words to materialise on the ether and he always says the opposite of what you think he might or should say. The man and his art possess the discrete charm of an intelligence which is thinly veiled by a seductive bravado. Contrary to the Legend of Schnabel, which tells of wild riots and loose morals, he is both more thoughtful and less vulgar than you might think. He seems disarmingly sincere and devoted to his art when he tells the assembled journalists that he does not represent anything in his paintings but only presents things.

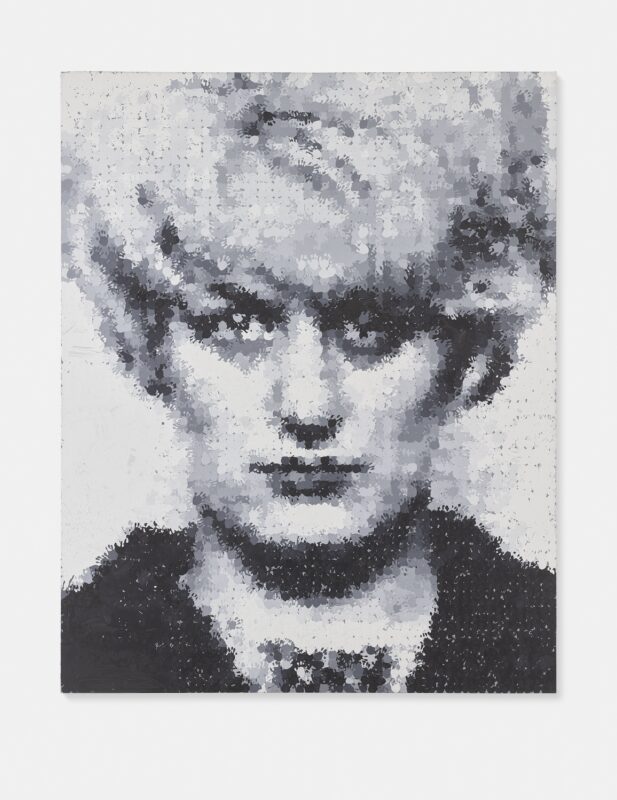

To those of us who had our induction into the cult of contemporary art through the conceptually heavy but ideologically light YBAs, Schnabel’s paintings are a breath of fresh air: they possess the urgency of a postmodern orientation towards history that seamlessly melds with an individual style, boldly executed with immediacy and precision, blurring a line between figuration and abstraction. It is that visceral self-confidence that the artworld fell in love with and made Schnabel an expensive, trailblazing celebrity artist.

The Schnabel story is full of thrills and careless whispers. Having gained his BFA from the University of Houston, an audacious Schnabel masterminded his return to his native New York via the Independent Study Programme at the Whitney with slides of his paintings encased between slices of bread. At the age of 24 he held his first solo museum show at the Contemporary Art Center, Houston, and four years later sold out the entirety of his first solo show at Mary Boone Gallery before it even opened. Having participated in the 1980 Venice Biennale, Schnabel gained joint representation by Mary Boone and Leo Castelli – of Warhol and Rauschenberg fame – with a major exhibition in 1981.

Schnabel was everywhere. He quickly ingratiated himself with the bustling New York scene, hanging out with Warhol and Basquiat, walking around in his silk pyjamas, travelling the world with exhibitions, going to parties and saying outlandish things like ‘I’m the closest thing to Picasso you’ll see in this fucking life’. He was brash and arrogant, as were his paintings, which he mostly made from broken plates, tarpaulin and mirrors, sometimes weathered in a hurricane or dragged on the tarmac behind a fast-moving car, often at billboard scale. He did features for glossy lifestyle magazines, posing shirtless at his Long Island studio like some beastly hybrid of David Beckham’s domestic glamour and Marlon Brando’s macho posturing. By 1984 Schnabel was a gossip column regular, so when he dumped his doting gallerists for Pace, Leo Castelli wrote a scathing article in the New York Times comparing him to King Kong. Nowadays, it is said, nobody who worked with him in the 80s will talk about him, perhaps still wounded by the trauma or subject to a gagging order.

An artist whose commercial success seems to know no bounds and who narcissistically compares himself to van Gogh is destined for a nasty fall. By the time of his 1987 mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Schnabel’s Cristal ball began to foresee hard times ahead. Although the fashion in contemporary art changed and the market slowed in the face of recession, a recent galleristNY article wondered whether the artworld was ready to forgive him, suggesting the Fall of Schnabel was as much about personality as it was about painting. A critical backlash concluded he epitomised the ugly excess of the decade and his work was suddenly denounced as pretentious and tacky. A particularly cutting review of his Whitney show said that the paintings, hardly a few years old, had not stood the test of time. Even though he remained a prolific painter with an almost religious devotion to his art, the artworld was exhausted and looking elsewhere for its kicks. Schnabel retreated into film, directing the highly acclaimed Basquiat and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, as well as launching Javier Bardem’s career with Before Night Falls.

After a hiatus between 2002 and 2011, however, Schnabel returned, most notably with a retrospective at the Museo Correr in Venice during the last Biennale and last year’s epic show at the Brant Foundation. This new exhibition at the Dairy Art Centre, with concurrent shows at Gagosian, Karma and Dallas Contemporary, hails the Second Coming of Schnabel, bringing him to a new audience, a new generation of artists and a more self-consciously calculated artworld. When he started out, the artworld was a barren place: painting was apparently dead, the market was famished and there were so many free column inches just waiting for artists to make a spectacle of themselves. He re-emerges now into an artworld of mystifying plenitude.

Now we view Schnabel through the misty lens of an art market that defies economic trends and an artworld saturated with celebrity artists who peddle glittering conceptualism to hedgefund managers. In this light, the materials, methods and myths of Schnabel’s paintings evoke a raw expressionism that somehow, against all odds, seems divested of its former life as a commercial product. These paintings are laced with Schnabel’s restless ambition to make painting matter; with the passing of time and the settling of scores, they possess the heroic quality of art as the artist’s inescapable calling which is so rare nowadays that we are almost wistful for it.

The sharks and Nazis of the YBAs seemed shocking to an artworld that had forgotten about Schnabel, an artworld that was so sterile in ideas and ravaged by recession that it behaved as if this sudden explosion was new. We now see that the 90s was an exaggeration of what had already happened in the 80s, where Schnabel was the Hirst of his time, so with the gift of hindsight, Schnabel suddenly feels steady, reliable, dependable.

Although he soared to fame quickly and without a shred of dignity, Schnabel smoulders with a constant, iridescent light that flickers in and out of consciousness but never entirely burns out. The secret to his longevity is that he makes art out of necessity, although perhaps a little more quietly these days, for as ee cummings said, ‘a rolling Schnabel gathers no sparks/the same hold true for Karl the Marks’.

Words: Daniel Barnes